Varanasi

Varanasi

Vārāṇasī Benares, Banaras, Kashi | |

|---|---|

Left to right, top to bottom: Manikarnika Ghat, the holy cremation ground on the Ganges river front; Kashi Vishwanath Temple; Faculty of Arts, Benares Hindu University; Goswami Tulsidas, composer of the Ramcharitmanas; weaving silk brocade; Benares Sanskrit College, India's oldest Sanskrit college (founded in 1791); and Munshi Ghat | |

Interactive map of Varanasi | |

| Coordinates: 25°19′08″N 83°00′46″E / 25.31889°N 83.01278°E | |

| Country | India |

| State | Uttar Pradesh |

| Division | Varanasi |

| District | Varanasi |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipal Corporation |

| • Body | Varanasi Municipal Corporation |

| • Mayor | Ashok Tiwari[2] (BJP) |

| • Municipal Commissioner | Pranay Singh, IAS |

| Area | |

| 82 km2 (32 sq mi) | |

| • Metro | 163.8 km2 (63.2 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 80.71 m (264.80 ft) |

| Population (2011) | |

| 1,212,610[1] | |

| • Rank | 30th |

| • Density | 37,500/km2 (97,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,432,280 (32nd) |

| Demonym | Banarasi |

| Language | |

| • Official | Hindi[6] |

| • Additional official | Urdu[6] |

| • Regional | Bhojpuri |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| PIN | 221 001 to** (** area code) |

| Telephone code | 0542 |

| Vehicle registration | UP-65 |

| GDP | $3.8 billion (2019–20)[7] |

| Per capita income | INR 1,93 616[8] |

| International Airport | Lal Bahadur Shastri International Airport |

| Rapid Transit | Varanasi Metro |

| Sex ratio | 0.926 (2011) ♂/♀ |

| Literacy (2011) | 80.31%[9] |

| HDI | 0.812[10] |

| Website | varanasi |

Varanasi (Hindi pronunciation: [ʋaːˈraːɳəsi],[a][b] also Benares, Banaras Hindustani pronunciation: [bəˈnaːrəs][c][12][13][14] or Kashi[d][15]) is a city on the Ganges river in northern India that has a central place in the traditions of pilgrimage, death, and mourning in the Hindu world.[16][e] The city has a syncretic tradition of Islamic artisanship that underpins its religious tourism.[19] Located in the middle-Ganges valley in the southeastern part of the state of Uttar Pradesh, Varanasi lies on the left bank of the river. It is 692 kilometres (430 mi) to the southeast of India's capital New Delhi and 320 kilometres (200 mi) to the southeast of the state capital, Lucknow. It lies 121 kilometres (75 mi) downstream of Prayagraj, where the confluence with the Yamuna river is another major Hindu pilgrimage site.

Varanasi is one of the world's oldest continually inhabited cities.[20][21][22] Kashi, its ancient name, was associated with a kingdom of the same name of 2,500 years ago. The Lion capital of Ashoka at nearby Sarnath has been interpreted to be a commemoration of the Buddha's first sermon there in the fifth century BCE.[23][24] In the 8th century, Adi Shankara established the worship of Shiva as an official sect of Varanasi. Tulsidas wrote his Awadhi language epic, the Ramcharitmanas, a Bhakti movement reworking of the Sanskrit Ramayana, in Varanasi. Several other major figures of the Bhakti movement were born in Varanasi, including Kabir and Ravidas.[25] In the 16th century, Rajput nobles in the service of the Mughal emperor Akbar, sponsored work on Hindu temples in the city in an empire-wide architectural style.[26][27] In 1740, Benares, a zamindari estate, was established in the vicinity of the city in the Mughal Empire's semi-autonomous province of Awadh.[28] Under the Treaty of Faizabad, the East India Company acquired Benares in 1775.[29][30] The city became a part of the Benares Division of British India's Ceded and Conquered Provinces in 1805, the North-Western Provinces in 1836, United Provinces in 1902, and of the Republic of India's state of Uttar Pradesh in 1950.[31]

Silk weaving, carpets, crafts and tourism employ a significant number of the local population, as do the Banaras Locomotive Works and Bharat Heavy Electricals. The city is known worldwide for its many ghats—steps leading down the steep river bank to the water—where pilgrims perform rituals. Of particular note are the Dashashwamedh Ghat, the Panchganga Ghat, the Manikarnika Ghat, and the Harishchandra Ghat, the last two being where Hindus cremate their dead. The Hindu genealogy registers at Varanasi are kept here. Among the notable temples in Varanasi are the Kashi Vishwanath Temple of Shiva, the Sankat Mochan Hanuman Temple, and the Durga Temple.

The city has long been an educational and musical centre: many prominent Indian philosophers, poets, writers, and musicians live or have lived in the city, and it was the place where the Benares gharana form of Hindustani classical music was developed. In the 20th-century, the Hindi-Urdu writer Premchand and the shehnai player Bismillah Khan were associated with the city. India's oldest Sanskrit college, the Benares Sanskrit College, was founded by Jonathan Duncan, the resident of the East India Company in 1791. Later, education in Benares was greatly influenced by the rise of Indian nationalism in the late 19th-century. Annie Besant founded the Central Hindu College in 1898. In 1916, she and Madan Mohan Malviya founded the Banaras Hindu University, India's first modern residential university. Kashi Vidyapith was established in 1921, a response to Mahatma Gandhi's non-cooperation movement.

Etymology

Traditional etymology links "Varanasi" to the names of two Ganges tributaries forming the city's borders: Varuna, still flowing in northern Varanasi, and Assi, today a small stream in the southern part of the city, near Assi Ghat. The old city is located on the north shores of the Ganges, bounded by Varuna and Assi.[32]

In the Mahabharata and in ancient India, the city is referred to as Kāśī from the Sanskrit verbal root kaś- "to shine", making Varanasi known as "City of Light",[33][15] the "luminous city as an eminent seat of learning".[34] The name was also used by pilgrims dating from Buddha's days.[citation needed] Kashi is still widely popular.

Hindu religious texts use many epithets in Sanskrit to refer to Varanasi, such as Kāśikā (transl. "the shining one"), Avimukta (transl. "never forsaken by Shiva"), Ānaṃdakānana (transl. "the forest of bliss"), Rudravāsa (transl. "the place where Rudra resides"), and Mahāśmaśāna (transl. "the great cremation ground").[35]

History

Mythology

According to Hindu mythology, Varanasi was founded by Shiva,[36] one of three principal deities along with Brahma and Vishnu. During a conflict between Brahma and Shiva, one of Brahma's five heads was torn off by Shiva. As was the custom, the victor carried the slain adversary's head in his hand and let it hang down from his hand as an act of ignominy, and a sign of his own bravery. A bridle was also put into the mouth. Shiva thus dishonoured Brahma's head, and kept it with him at all times. When he came to the city of Varanasi in this state, the hanging head of Brahma dropped from Shiva's hand and disappeared in the ground. Varanasi is therefore considered an extremely holy site.[37]

The Pandavas, the protagonists of the Hindu epic Mahabharata, are said to have visited the city in search of Shiva to atone for their sins of fratricide and brahmahatya that they had committed during the Kurukshetra War.[38] It is regarded as one of seven holy cities (Sapta Puri) which can provide Moksha; Ayodhya, Mathura, Haridwar, Kashi, Kanchipuram, Avanti, and Dvārakā are the seven cities known as the givers of liberation.[39] The princesses Ambika and Ambalika of Kashi were wed to the Hastinapur ruler Vichitravirya, and they later gave birth to Pandu and Dhritarashtra. Bhima, a son of Pandu, married a Kashi princess Valandhara and their union resulted in the birth of Sarvaga, who later ruled Kashi. Dhritarasthra's eldest son Duryodhana also married a Kashi princess Bhanumati, who later bore him a son Lakshmana Kumara and a daughter Lakṣmaṇā.[40]

The Cakkavatti Sīhanāda Sutta text of Buddhism puts forth an idea stating that Varanasi will one day become the fabled kingdom of Ketumati in the time of Maitreya.[41]

Ancient period

Excavations in 2014 led to the discovery of artefacts dating back to 800 BCE. Further excavations at Aktha and Ramnagar, two sites in the vicinity of the city, unearthed artefacts dating back to 1800 BCE, supporting the view that the area was inhabited by this time.[42]

During the time of Gautama Buddha, Varanasi was part of the Kingdom of Kashi.[43] The celebrated Chinese traveller Xuanzang, also known as Hiuen Tsiang, who visited the city around 635 CE, attested that the city was a centre of religious and artistic activities, and that it extended for about 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) along the western bank of the Ganges.[43][44] When Xuanzang visited Varanasi in the 7th century, he named it "Polonise" (Chinese: 婆羅痆斯; pinyin: Póluó niè sī; lit. 'Brahma') and wrote that the city had some 30 temples with about 30 monks.[45] The city's religious importance continued to grow in the 8th century, when Adi Shankara established the worship of Shiva as an official sect of Varanasi.[46]

Medieval period

Chandradeva, founder of the Gahadavala dynasty made Banaras a second capital in 1090.[47] In 1194 CE, the Ghurid conqueror Muizzuddin Muhammad Ghuri defeated the forces of Jayachandra in a battle near Jamuna and afterwards ravaged the city of Varnasi in the course of which many temples were destroyed.[48]

Varanasi remained a centre of activity for intellectuals and theologians during the Middle Ages, which further contributed to its reputation as a cultural centre of religion and education. Several major figures of the Bhakti movement were born in Varanasi, including Kabir who was born here in 1389,[49] and Ravidas, a 15th-century socio-religious reformer, mystic, poet, traveller, and spiritual figure, who was born and lived in the city and employed in the tannery industry.[50][51]

Early Modern to Modern periods (1500–1949)

-

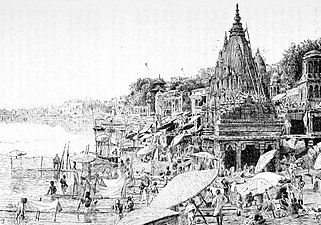

A lithograph by James Prinsep of a Brahmin placing a garland on the holiest location in the city

-

A painting by Lord Weeks (1883) of Varanasi, viewed from the Ganges

-

An illustration (1890) of a bathing ghat in Varanasi

Numerous eminent scholars and preachers visited the city from across India and South Asia. Guru Nanak visited Varanasi for Maha Shivaratri in 1507. Kashi (Varanasi) played a large role in the founding of Sikhism.[52]

In 1567 or thereabouts, the Mughal emperor Jallaludin Muhammad Akbar sacked the city of Varanasi on his march from Allahabad (modern-day Prayagraj).[53] However, later the Kachwaha Rajput rulers of Amber (Mughal vassals themselves) most notably under Raja Man Singh rebuilt various temples and ghats in the city.[54]

The Raja of Jaipur established the Annapurna Mandir, and the 200-metre (660 ft) Akbari Bridge was also completed during this period.[55] The earliest tourists began arriving in the city during the 16th century.[56] In 1665, the French traveller Jean-Baptiste Tavernier described the architectural beauty of the Vindu Madhava temple on the side of the Ganges. The road infrastructure was also improved during this period. It was extended from Kolkata to Peshawar by Emperor Sher Shah Suri; later during the British Raj it came to be known as the famous Grand Trunk Road. In 1656, Emperor Aurangzeb ordered the destruction of many temples and the building of mosques, causing the city to experience a temporary setback.[44] However, after Aurangzeb's death, most of India was ruled by a confederacy of pro-Hindu kings. Much of modern Varanasi was built during this time, especially during the 18th century by the Maratha and Bhumihar Brahmin rulers.[57] The kings governing Varanasi continued to wield power and importance through much of the British Raj period, including the Maharaja of Benares, or simply called by the people of Benares as Kashi Naresh.[58][59]

The Kingdom of Benares was given official status by the Mughals in 1737, and the kingdom started in this way and continued as a dynasty-governed area until Indian independence in 1947, during the reign of Vibhuti Narayan Singh. In the 18th century, Muhammad Shah ordered the construction of an observatory on the Ganges, attached to Man Mandir Ghat, designed to discover imperfections in the calendar in order to revise existing astronomical tables. Tourism in the city began to flourish in the 18th century.[56] As the Mughal suzerainty weakened, the Benares zamindari estate became Banaras State, thus Balwant Singh of the Narayan dynasty regained control of the territories and declared himself Maharaja of Benares in 1740.[60] The strong clan organisation on which they rested, brought success to the lesser known Hindu princes.[61] There were as many as 100,000 men backing the power of the Benares rajas in what later became the districts of Benares, Gorakhpur and Azamgarh.[61] This proved a decisive advantage when the dynasty faced a rival and the nominal suzerain, the Nawab of Oudh, in the 1750s and the 1760s.[61]

An exhausting guerrilla war, waged by the Benares ruler against the Oudh camp, using his troops, forced the Nawab to withdraw his main force.[61] The region eventually ceded by the Nawab of Oudh to the Benares State, a subordinate of the East India Company, in 1775, who recognised Benares as a family dominion.[62][63] In 1791 under the rule of the British, resident Jonathan Duncan founded a Sanskrit College in Varanasi.[64] In 1867, the establishment of the Varanasi Municipal Board led to significant improvements in the city's infrastructure and basic amenities of health services, drinking water supply and sanitation.[65]

Rev. M. A. Sherring in his book The Sacred City of Hindus: An account of Benaras in ancient and modern times published in 1868 refers to a census conducted by James Prinsep and put the total number of temples in the city to be around 1000 during 1830s. He writes,[66]

The history of a country is sometimes epitomised in the history of one of its principal cities. The city of Benaras represents India religiously and intellectually, just as Paris represents the political Sentiments of France. There are few cities in the world of greater antiquity, and none that have so uninterruptedly maintained their ancient celebrity and distinction.

Author Mark Twain wrote in 1897 of Varanasi,[67]

Benares is older than history, older than tradition, older even than legend, and looks twice as old as all of them put together.

Benares became a princely state in 1911,[62] with Ramnagar as its capital, but with no jurisdiction over the city proper. The religious head, Kashi Naresh, has had his headquarters at the Ramnagar Fort since the 18th century, also a repository of the history of the kings of Varanasi, which is situated to the east of Varanasi, across the Ganges.[68] The Kashi Naresh is deeply revered by the local people and the chief cultural patron; some devout inhabitants consider him to be the incarnation of Shiva.[69]

Annie Besant founded the Central Hindu College, which later became a foundation for the creation of Banaras Hindu University in 1916. Besant founded the college because she wanted "to bring men of all religions together under the ideal of brotherhood in order to promote Indian cultural values and to remove ill-will among different sections of the Indian population."[70]

Varanasi was ceded to the Union of India in 1947, becoming part of Uttar Pradesh after Indian independence.[71] Vibhuti Narayan Singh incorporated his territories into the United Provinces in 1949.[72]

-

Maharaja of Benares, 1870s

-

Map of the city, c. 1914

-

An 1895 photograph of the Varanasi riverfront

-

The lanes of Varanasi are bathed in a plethora of colours.

21st-century

Narendra Modi, prime minister of India since 2014, has represented Varanasi in the Parliament of India since 2014. Modi inaugurated the Shri Kashi Vishwanath Corridor project, which aimed to enhance the city's spiritual vibrancy by connecting many ghats to the temple of Kashi Vishwanath, in December 2021.[73]

Geography and climate

Geography

Varanasi is located at an elevation of 80.71 metres (264.8 ft)[74] in the centre of the Ganges valley of North India, in the Eastern part of the state of Uttar Pradesh, along the left crescent-shaped bank of the Ganges, averaging between 15 metres (50 ft) and 21 metres (70 ft) above the river.[75] The city is the headquarters of Varanasi district. By road, Varanasi is located 797 kilometres (495 mi) south-east of New Delhi, 320 kilometres (200 mi) south-east of Lucknow, 121 kilometres (75 mi) east of Prayagraj, and 63 kilometres (39 mi) south of Jaunpur.[76] The "Varanasi Urban Agglomeration" – an agglomeration of seven urban sub-units – covers an area of 112 km2 (43 sq mi).[77] Neighbourhoods of the city include Adampura, Anandbagh, Bachchhaon, Bangali Tola, Bhelpura, Bulanala, Chaitganj, Chaukaghat, Chowk, Dhupchandi, Dumraon, Gandhinagar, Gautam Nagar, Giri Nagar, Gopal Vihar, Guru Nanak Nagar, Jaitpura, Kail Garh, Khanna, Kotwali, Lanka Manduadih, Luxa, Maheshpur, Mahmoorganj, Maulvibagh, Nagwar, Naipokhari, Shivala, Siddhagiribagh, and Sigra.[76]

Located in the Indo-Gangetic Plains of North India, the land is very fertile because low-level floods in the Ganges continually replenish the soil.[78] Varanasi is situated between the Ganges confluences with two rivers: the Varuna and the Assi stream. The distance between the two confluences is around 2 miles (4 km), and serves as a sacred journeying route for Hindus, which culminates with a visit to a Sakshi Vinayak Temple.[79]

Climate

Varanasi experiences a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cwa) with large variations between summer and winter temperatures.[80][81] The dry summer starts in April and lasts until June, followed by the monsoon season from July to October. The temperature ranges between 22 and 46 °C (72 and 115 °F) in the summers. Winters in Varanasi see very large diurnal variations, with warm days and downright cold nights. Cold waves from the Himalayan region cause temperatures to dip across the city in the winter from December to February and temperatures below 5 °C (41 °F) are not uncommon. The average annual rainfall is 1,110 mm (44 in). Fog is common in the winters, while hot dry winds, called loo, blow in the summers.[82] In recent years, the water level of the Ganges has decreased significantly; upstream dams, unregulated water extraction, and dwindling glacial sources due to global warming may be to blame.[83][84]

| Climate data for Varanasi (1991–2020, extremes 1901–2012) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32.5 (90.5) |

36.1 (97.0) |

41.5 (106.7) |

45.3 (113.5) |

47.2 (117.0) |

47.2 (117.0) |

45.0 (113.0) |

40.1 (104.2) |

39.8 (103.6) |

39.4 (102.9) |

37.1 (98.8) |

32.8 (91.0) |

47.2 (117.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 21.9 (71.4) |

26.7 (80.1) |

32.8 (91.0) |

38.9 (102.0) |

40.4 (104.7) |

38.5 (101.3) |

33.8 (92.8) |

33.1 (91.6) |

33.1 (91.6) |

32.5 (90.5) |

29.2 (84.6) |

24.1 (75.4) |

32.1 (89.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 9.0 (48.2) |

12.4 (54.3) |

16.7 (62.1) |

22.1 (71.8) |

25.9 (78.6) |

27.8 (82.0) |

26.6 (79.9) |

26.2 (79.2) |

25.3 (77.5) |

20.9 (69.6) |

14.5 (58.1) |

10.1 (50.2) |

19.7 (67.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 1.0 (33.8) |

1.7 (35.1) |

6.7 (44.1) |

11.1 (52.0) |

17.3 (63.1) |

20.5 (68.9) |

20.0 (68.0) |

20.4 (68.7) |

16.4 (61.5) |

11.7 (53.1) |

5.0 (41.0) |

2.2 (36.0) |

1.0 (33.8) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 16.3 (0.64) |

21.7 (0.85) |

10.8 (0.43) |

7.3 (0.29) |

13.8 (0.54) |

100.8 (3.97) |

265.2 (10.44) |

282.9 (11.14) |

224.5 (8.84) |

33.0 (1.30) |

5.5 (0.22) |

3.9 (0.15) |

985.9 (38.81) |

| Average rainy days | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 5.2 | 12.3 | 12.9 | 8.6 | 1.9 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 48.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 17:30 IST) | 65 | 52 | 37 | 28 | 32 | 51 | 74 | 79 | 78 | 71 | 69 | 70 | 59 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 232.5 | 240.1 | 291.4 | 294.0 | 300.7 | 234.0 | 142.6 | 189.1 | 195.0 | 257.3 | 261.0 | 210.8 | 2,848.5 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 7.5 | 8.5 | 9.4 | 9.8 | 9.7 | 7.8 | 4.6 | 6.1 | 6.5 | 8.3 | 8.7 | 6.8 | 7.8 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 6 | 7 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 9 |

| Source 1: India Meteorological Department (sun 1971–2000)[85][86][87][88] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas[89] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Varanasi Airport (1991–2020, extremes 1952–2012) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32.3 (90.1) |

35.8 (96.4) |

42.4 (108.3) |

46.7 (116.1) |

46.8 (116.2) |

48.0 (118.4) |

43.9 (111.0) |

39.8 (103.6) |

42.3 (108.1) |

39.0 (102.2) |

35.3 (95.5) |

32.7 (90.9) |

48.0 (118.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 22.2 (72.0) |

26.9 (80.4) |

33.3 (91.9) |

39.3 (102.7) |

40.7 (105.3) |

38.9 (102.0) |

34.3 (93.7) |

33.3 (91.9) |

33.4 (92.1) |

33.1 (91.6) |

29.7 (85.5) |

24.4 (75.9) |

32.5 (90.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 8.9 (48.0) |

12.2 (54.0) |

16.5 (61.7) |

21.9 (71.4) |

25.7 (78.3) |

27.5 (81.5) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.1 (79.0) |

25.2 (77.4) |

21.0 (69.8) |

14.8 (58.6) |

10.2 (50.4) |

19.8 (67.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 0.3 (32.5) |

2.4 (36.3) |

4.0 (39.2) |

11.4 (52.5) |

17.8 (64.0) |

14.3 (57.7) |

21.4 (70.5) |

21.5 (70.7) |

19.1 (66.4) |

8.9 (48.0) |

4.3 (39.7) |

2.3 (36.1) |

0.3 (32.5) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 14.2 (0.56) |

19.3 (0.76) |

9.4 (0.37) |

10.3 (0.41) |

16.7 (0.66) |

108.8 (4.28) |

293.7 (11.56) |

259.3 (10.21) |

206.9 (8.15) |

30.6 (1.20) |

4.8 (0.19) |

2.7 (0.11) |

976.8 (38.46) |

| Average rainy days | 1.4 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 5.3 | 12.5 | 12.4 | 8.5 | 1.8 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 47.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 17:30 IST) | 64 | 52 | 36 | 24 | 30 | 49 | 73 | 78 | 76 | 65 | 61 | 66 | 56 |

| Source: India Meteorological Department[85][86][88] | |||||||||||||

Varanasi has been ranked 9th best “National Clean Air City” (under Category 1 >10L Population cities) in India.[90]

Demographics

According to provisional data from the 2011 census, the Varanasi urban agglomeration had a population of 1,435,113, with 761,060 men and 674,053 women.[91] The Varanasi municipal corporation and CB had a combined population of 1,212,610 of which 642,882 were males and 569,728 in 2011. The population in the age group of 0 to 6 years was 137,111.[1]

The population of the Varanasi urban agglomeration in 2001 was 1,371,749 with a ratio of 879 females every 1,000 males.[92] However, the area under Varanasi Nagar Nigam has a population of 1,100,748[93] with a ratio of 883 females for every 1,000 males.[93] The literacy rate in the urban agglomeration is 77% while that in the municipal corporation area is 78%.[93] Approximately 138,000 people in the municipal area live in slums.[94]

Religion

Hinduism is predominantly followed in Varanasi with Islam being the largest minority. Nearly 70% of the population follows Hinduism. The city also agglomerate different religions such as Christianity, Sikhism, Jainism and Buddhism. The city is also a centre for Buddhist pilgrimage. At Sarnath, just northeast of Varanasi, the Buddha gave his first teaching (Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta) after attaining enlightenment. According to the Buddhavaṃsa, a hagiographical Buddhist text, Varanasi is stated to have been the birthplace of the previous Buddha, known as Kassapa Buddha.

In the sacred geography of India Varanasi is known as the "microcosm of India".[96] In addition to its 3,300 Hindu religious places, Varanasi has 12 churches, three Jain mandirs, nine Buddhist shrines, three Gurdwaras (Sikh shrines), and 1,388 Muslim holy places.[97]

Languages

Languages in Varanasi Municipal Corporation and Cantonment Board area, 2011 Census[98]

At the time of the 2011 Census of India, 83.87% of the population of Varansi Municipal Corporation and Cantonment Board spoke Hindi, 9.03% Urdu, 4.81% Bhojpuri, and 0.92% Bengali as their first language.[98]

Administration and politics

Administration

General administration

Varanasi division which consists of four districts, and is headed by the Divisional Commissioner of Varanasi, who is an IAS officer of high seniority, the Commissioner is the head of local government institutions (including Municipal Corporations) in the division, is in charge of infrastructure development in his division, and is also responsible for maintaining law and order in the division.[99][100][101][102][103] The District Magistrate of Varanasi reports to the Divisional Commissioner. The Commissioner is Deepak Agarwal.[104][105][106]

Varanasi district administration is headed by the District Magistrate of Varanasi, who is an IAS officer. The DM is in charge of property records and revenue collection for the central government and oversees the elections held in the city. The DM is also responsible for maintaining law and order in the city, hence the SSP of Varanasi also reports to the DM of Varanasi.[99][107][108][109][110] The DM is assisted by a Chief Development Officer (CDO), four Additional District Magistrates (ADM) (Finance/Revenue, City, Protocol, Executive), one chief revenue officer (CRO), one City Magistrate (CM), and four Additional City Magistrates (ACM). The district has three tehsils, each headed by a Sub-Divisional Magistrate. The DM is Kaushal Raj Sharma.[111][112][106]

Police administration

Varanasi district comes under the Varanasi Police Zone and Varanasi Police Range, Varanasi Zone is headed by an Additional Director General ranked IPS officer, and the Varanasi Range is headed Inspector General ranked IPS officer. The ADG, Varanasi Zone is Biswajit Mahapatra,[113] and IG, Varanasi Range is Vijay Singh Meena.[114]

The district police up to the date of 24 March 2021 was headed by a Senior Superintendent of Police (SSP), who is an IPS officer, and is assisted by six Superintendents of Police (SP)/Additional Superintendents of Police (Addl. SP) (City, Rural Area, Crime, Traffic, Protocol and Protocol), who are either IPS officers or PPS officers.[115] Each of the several police circles is headed by a Circle Officer (CO) in the rank of Deputy Superintendent of Police.[115] The last SSP was Amit Pathak.[115]

On 25 March 2021 the Government of Uttar Pradesh passed an order to divide the Varanasi police into Varanasi City Police and Rural Police.[116] Since then City Police is headed by the Commissioner of Police (CP), who is an IPS officer of ADGP rank, and is assisted by two additional commissioners of police (Addl. CP) who is of DIG rank, and two deputy commissioners of police (DCP) who are of SP rank. And Rural Police is headed by SP rank.[117]

Infrastructure and civic administration

The development of infrastructure in the city is overseen by the Varanasi Development Authority (VDA), which comes under the Housing Department of Uttar Pradesh government. The divisional commissioner of Varanasi acts as the ex-officio chairman of the VDA, whereas the vice-chairman, a government-appointed Indian Administrative Service (IAS) officer, looks after the daily matters of the authority.[118] The vice-chairman of the Varanasi Development Authority is Pulkit Khare.[119]

The Varanasi Municipal Corporation oversees civic activities in the city; the head of the corporation is the mayor, and the executive and administration of the corporation is the responsibility of the municipal commissioner, who is appointed by the government of Uttar Pradesh and is either an IAS officer or Provincial Civil Service (PCS) officer of high seniority. The mayor of Varanasi is Mridula Jaiswal, and the municipal commissioner is Nitin Bansal.[120]

Water supply and sewage system is operated by the Uttar Pradesh Jal Nigam.[121]

Politics

Varanasi is represented in the Lok Sabha by the Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi who won the Lok Sabha elections in 2014 and subsequently in 2019 by a huge margin.[122][123]

Healthcare

Hospitals in the city include the Sir Sunderlal Hospital, a teaching hospital in the Banaras Hindu University, Heritage Hospital, Marwari Hospital, Pitambari Hospital, Mata Anand Mai Hospital, Rajkiya Hospital, Ram Krishna Mission Hospital, Shiv Prasad Gupta Hospital, Pandit Deen Dayal Upadhyay Hospital (managed by the state government), and Varanasi Hospital and Medical Research Centre. The urban parts of the Varanasi district had an infant mortality rate of 70 per 1,000 live births in 2010–2011.[124] The Railway Cancer Hospital is now being run by the Tata Memorial Centre after intervention by Prime Minister Narendra Modi who represents Varanasi.[125]

Sushruta, an ancient Indian physician known as the primary author of the treatise Sushruta Samhita, the Sanskrit text of surgery, lived in Varanasi and practised medicine and surgery sometime during the 5th century BCE. Since 1922, Ayurveda has been a subject of training in the Banaras Hindu University, and in 1927 a separate Ayurvedic College was established.[126][127] There are many ayurvedic centres in Varanasi providing treatments such as Panchakarma as well as other treatments.[128]

Public maintenance

Because of the high population density of Varanasi and the increasing number of tourists, the Uttar Pradesh government and international non-governmental organisations and institutions have expressed grave concern for the pollution and pressures on infrastructure in the city, mainly the sewage, sanitation, and drainage components.[129] Pollution of the Ganges is a particular source of worry because of the religious significance of the river, the dependence of people on it as a source of drinking water, and its prominence as a symbol of Varanasi and the city itself.[130] The sewage problem is exacerbated by the role of the Ganges in bathing and in river traffic, which is very difficult to control.[129] Because of the sewage, people using local untreated water have higher risk of contracting a range of water-borne stomach diseases.[131]

Parts of Varanasi are contaminated with industrial chemicals including toxic heavy metal. Studies of wastewater from Varanasi's sewage treatment plants identify that water's contamination with metals and the reuse of this water for irrigation as a way that the toxic metals come to be in the plants that people grow for food.[132][133] One studied example is palak, a popular leafy vegetable which takes up heavy metal when it is in the soil, and which people then eat.[134] Some of the polluting sludge contains minerals which are fertiliser, which could make polluted water attractive to use.[135] Pesticides used in local farming are persistent enough to be spread through the water, to sewer treatment, then back to the farms as wastewater.[135]

Varanasi's water supply and sewage system is maintained by Jal Nigam, a subsidiary of Varanasi Nagar Nigam. Power supply is by the Uttar Pradesh Power Corporation Limited. The city produces about 350,000,000 litres (77,000,000 imp gal; 92,000,000 US gal) per day[136] of sewage and 425 tonnes (418 long tons; 468 short tons) per day of solid waste.[137] The solid wastes are disposed in one landfill site.[138]

Economy

According to the 2006 City Development Plan for Varanasi, approximately 29% of Varanasi's population is employed.[139] Approximately 40% are employed in manufacturing, 26% work in trade and commerce, 19% work in other services, 8% work in transport and communication, 4% work in agriculture, 2% work in construction, and 2% are marginal workers (working for less than half of the year).[140]

Among manufacturing workers, 51% work in spinning and weaving, 15% work in metal, 6% work in printing and publishing, 5% work in electrical machinery, and the rest work in a wide variety of industry sectors.[141] Varanasi's manufacturing industry is not well developed and is dominated by small-scale industries and household production.[139]

Silk weaving is the dominant industry in Varanasi.[142] Muslims are the influential community in this industry with nearly half a million of them working as weavers, dyers, sari finishers, and salespersons.[143] Weaving is typically done within the household, and most weavers are Momin Ansari Muslims.[144] Varanasi is known throughout India for its production of very fine silk and Banarasi saris, brocades with gold and silver thread work, which are often used for weddings and special occasions. The production of silk often uses bonded child labour, though perhaps not at a higher rate than elsewhere in India.[145] The silk weaving industry has recently been threatened by the rise of power looms and computer-generated designs and by competition from Chinese silk imports.[139] Trade Facilitation Centre is a modern and integrated facility to support the handloom and handicraft sector in Varanasi; providing trade enhancement and facilitation to both domestic and international buyers. Hence, carrying forward the rich traditions of handlooms and handicrafts.[citation needed]

In the metal manufacturing sector, Banaras Locomotive Works is a major employer.[141] Bharat Heavy Electricals, a large power equipment manufacturer, also operates a heavy equipment maintenance plant.[146] Other major commodities manufactured and traded in Varanasi include hand-knotted Mirzapur carpets, rugs, dhurries, brassware, copperware, wooden and clay toys, handicrafts, gold jewellery, and musical instruments.[142] Important agricultural products include betel leaves (for paan), langra mangoes and khoa (solidified milk).[141][147]

Tourism

Tourism is Varanasi's second most important industry.[148] Domestic tourist most commonly visit for religious purposes while foreign tourist visit for ghats along River Ganges and Sarnath. Most domestic tourists are from Bihar, West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh, and other parts of Uttar Pradesh, while the majority of foreign tourists are from Sri Lanka and Japan.[149] The peak tourist season falls between October and March.[149] In total, there are around 12,000 beds available in the city, of which about one half are in inexpensive budget hotels and one third in dharamsalas.[150] Overall, Varanasi's tourist infrastructure is not well developed.[150]

In 2017, InterContinental Hotels Group made an agreement with the JHV group to set up Holiday Inn and Crowne Plaza hotel chains in Varanasi.[151]

| Year | International | Domestic | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 285,252 | 4,966,161 | 5,251,413 |

| 2014 | 287,761 | 5,202,236 | 5,489,997 |

| 2015 | 302,370 | 5,413,927 | 5,716,297 |

| 2016 | 312,519 | 5,600,146 | 5,912,665 |

| 2017 | 334,708 | 5,947,355 | 6,282,063 |

| 2018 | 348,970 | 6,095,890 | 6,444,860 |

| 2019 | 350,000 | 6,447,775 | 6,797,775 |

The prominent malls and multiplexes in Varanasi are JHV Mall in the Cantonment area, IP Mall in Sigra, IP Vijaya Mall in Bhelupur, Vinayak Plaza in Maldhaiya and PDR Mall in Luxa.

Notable landmarks

Apart from the 19 archaeological sites identified by the Archaeological Survey of India,[154] some of the prominent places of interest are the Aghor Peeth, the Alamgir Mosque, the Ashoka Pillar, the Bharat Kala Bhavan (Art Museum), the Bharat Mata Mandir, the Central University for Tibetan Studies, the Dhanvantari Temple, the Durga Temple, the Jantar Mantar, the Kashi Vishwanath Temple, the Sankat Mochan Hanuman Temple, the Mahatma Gandhi Kashi Vidyapith, the Shri Vishwanath Temple on the BHU campus, the Ramnagar Fort, the Riverfront Ghats, the Tulsi Manas Temple.[155]

Jantar Mantar

The Jantar Mantar observatory, constructed in 1737, is located above the ghats along the Ganges, and is adjacent to the Manmandir and Dasaswamedh Ghats and near the palace of Jai Singh II of Jaipur. While less equipped than the observatories at Jaipur and Delhi, the Jantar Mantar has a unique equatorial sundial which is functional and allows measurements to be monitored and recorded by one person.[156]

Ramnagar Fort

The Ramnagar Fort, located near the Ganges on its eastern bank and opposite the Tulsi Ghat, was built in the 18th century by Kashi Naresh Raja Balwant Singh with cream-coloured chunar sandstone. The fort is a typical example of the Mughal architecture with carved balconies, open courtyards, and scenic pavilions. At present, the fort is in disrepair. The fort and its museum are the repository of the history of the kings of Benares. Cited as an "eccentric" museum, it contains a rare collection of American vintage cars, bejewelled sedan chairs, an impressive weaponry hall, and a rare astrological clock.[157] In addition, manuscripts, especially religious writings, are housed in the Saraswati Bhawan which is a part of a museum within the fort. Many books illustrated in the Mughal miniature style are also part of the collections. Because of its scenic location on the banks of the Ganges, it is frequently used as an outdoor shooting location for films.[157][158]

Ghats

The Ghats in Varanasi are world-renowned embankments made in steps of stone slabs along the river bank where pilgrims perform ritual ablutions.[159] The ghats are an integral complement to the Hindu concept of divinity represented in physical, metaphysical, and supernatural elements.[160] Varanasi has at least 84 ghats, most of which are used for bathing by pilgrims and spiritually significant Hindu puja ceremony, while a few are used exclusively as Hindu cremation sites.[161][162][163] Steps in the ghats lead to the banks of Ganges, including the Dashashwamedh Ghat, the Manikarnika Ghat, the Panchganga Ghat, and the Harishchandra Ghat, where Hindus cremate their dead. Many ghats are associated with Hindu legends and several are now privately owned.[164]

Many of the ghats were constructed under the patronage of the Marathas like Scindias, Holkars, Bhonsles, and Peshwas. Most are bathing ghats, while others are used as cremation sites. A morning boat ride on the Ganges across the ghats is a popular tourist attraction. The extensive stretches of ghats in Varanasi enhance the riverfront with a multitude of shrines, temples, and palaces built "tier on the tier above the water's edge".[43]

The Dashashwamedh Ghat is the main and probably the oldest ghat of Varanasi located on the Ganges, close to the Kashi Vishwanath Temple.[citation needed]

It is believed that Brahma created this ghat to welcome Shiva and sacrificed ten horses during the Dasa-Ashwamedha yajna performed there. Above and adjacent to this ghat, there are also temples dedicated to Sulatankesvara, Brahmesvara, Varahesvara, Abhaya Vinayaka, Ganga (the Ganges), and Bandi Devi, which are all important pilgrimage sites. A group of priests performs "Agni Pooja" (Sanskrit: "Worship of Fire") daily in the evening at this ghat as a dedication to Shiva, Ganga, Surya (Sun), Agni (Fire), and the entire universe. Special aartis are held on Tuesdays and on religious festivals.[162]

The Manikarnika Ghat is the Mahasmasana, the primary site for Hindu cremation in the city. Adjoining the ghat, there are raised platforms that are used for death anniversary rituals. According to a myth, it is said that an earring of Shiva or his wife Sati fell here. Fourth-century Gupta period inscriptions mention this ghat. However, the current ghat as a permanent riverside embankment was built in 1302 and has been renovated at least three times throughout its existence.[162]

The Jain Ghat is believed to birthplace of Suparshvanatha (7th Tirthankara) and Parshvanatha (23rd tirthankara). The Jain Ghat or Bachraj Ghat is a Jain Ghat and has three Jain Temples located on the banks of the River. It is believed that the Jain Maharajas used to own these ghats. Bachraj Ghat has three Jain temples near the river's banks, and one them is a very ancient temple of Tirthankara Suparswanath.[citation needed]

- Ghats in Varanasi

-

The Jain Ghat/Bachraj Ghat

-

Kedar Ghat during Kartika Purnima

Temples

-

The Kashi Vishwanath Temple, the most important temple in Varanasi.

-

Shri Vishwanath Mandir has the tallest temple tower in the world.[165]

-

The 18th century Durga Kund Temple

Among the estimated 23,000 temples in Varanasi,[38] the temples most popular for worship are: the Kashi Vishwanath Temple of Shiva; the Sankat Mochan Hanuman Temple; and the Durga Temple, known for monkeys that reside in the large trees nearby.[71][166][32]

- The Kashi Vishwanath Temple, on the Ganges, is one of the 12 Jyotirlinga Shiva temples in Varanasi.[166] The temple has been destroyed and rebuilt several times throughout its existence. The Gyanvapi Mosque, which is adjacent to the temple, is the original site of the temple.[167] The temple, which is also known as the Golden Temple,[168] was built in 1780 by Queen Ahilyabai Holkar of Indore. The two pinnacles of the temple are covered in gold and were donated in 1839 by Ranjit Singh, the ruler of Punjab. The dome is scheduled to receive gold plating through a proposed initiative of the Ministry of Culture and Religious Affairs of Uttar Pradesh. Numerous rituals, prayers, and aartis are held daily at the temple between 02:30 and 23:00.[169]

- The Sankat Mochan Hanuman Temple, which is situated by the Asi River, is one of the sacred temples of the Hindu god Hanuman.[170] The present temple was built in the early 1900s by the educationist and Indian independence figure, Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya, the founder of Banaras Hindu University.[171] According to Hindu legend the temple was built on the spot where the medieval Hindu saint Tulsidas had a vision of Hanuman.[172] During a 7 March 2006 terrorist attack, one of three explosions hit the temple while a wedding was in progress, and resulted in injuries to 30 people apart from 23 deaths.[171] Following the attack, a permanent police post was installed inside the temple.[173]

- There are two temples dedicated to the goddess Durga in Varanasi: Durga Mandir built in the 16th century (exact date not known), and Durga Kund (Sanskrit 'kund' meaning "pond or pool") built in the 18th century. A large number of Hindu devotees visit Durga Kund during Navratri to worship the goddess Durga. The temple, built in the Nagara architectural style, has multi-tiered spires[168] and is stained red with ochre, representing the red colour of Durga. The building has a rectangular tank of water called the Durga Kund ("Kund" meaning a pond or pool). During annual celebrations of Nag Panchami, the act of depicting the god Vishnu reclining on the serpent Shesha is recreated in the Kund.[174] While the Annapurna Temple, located nearby to the Kashi Vishwanath Temple, is dedicated to Annapoorna devi, the goddess of food,[166] the Sankatha Temple adjacent to the Sindhia Ghat is dedicated to Sankatha, the goddess of remedy. The Sankatha Temple has a large sculpture of a lion and a cluster of nine smaller temples dedicated to the nine planets.[166]

- Parshvanath Jain temple is the temple of Jain religion dedicated to Parshvanath, the 23rd Thirthankara who was born at Bhelpur in Varanasi. The idol deified in the temple is of black colour and 75 centimetres (30 inches) in height. It is located in Bhelapur about 5 kilometres (3.1 miles) from the centre of Varanasi city and 3 kilometres (1.9 miles) from the Benares Hindu University. It belongs to the Digambar sect of Jainism and is a holy tirtha or pilgrimage centre for Jains.

- Other temples of note are: the Bharat Mata Mandir, dedicated to the national personification of India, which was inaugurated by Mahatma Gandhi in 1936, the Kalabhairav Temple, the Mrithyunjay Mahadev Temple, and the New Vishwanath Temple located in the campus of BHU, the Tulsi Manas Mandir.[166]

Mosques

There are 15 mosques of significant historical value in Varanasi. Of particular note are the Abdul Razzaq, Alamgir, Bibi Razia, Chaukhambha, Dhai Nim Kangore, Fatman, Ganje Shahada, Gyanavapi, and Hazrat Sayyed Salar Masud Dargah. Many of these mosques were constructed from the components of the Hindu shrines which were destroyed under the auspices of subsequent Muslim invaders or rulers. The two such well known mosques are the Gyanvapi Mosque and the Alamgir Mosque.[175]

The Gyanvapi Mosque was built by the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in 1664 CE, after destroying a Hindu temple.[176] Gyan Vapi (Sanskrit: "the well of knowledge"), the name of the mosque, is derived from a well of the same name located within the precincts of the mosque.[177] The remains of an erstwhile temple can be seen in the foundation, the columns and at the rear part of the mosque.[178] The façade of the mosque is modelled partially on the Taj Mahal's entrance.[179] The mosque is administered by the Anjuman Inthazamiya Masajid (AIM).[180]

The Alamgiri Mosque was built in the 17th century by Aurangzeb over the ruins of a Hindu temple.[181] The Hindu temple that was destroyed was dedicated to Vishnu, and had been built by Beni Madhur Rao Scindia, a Maratha chieftain. When emperor Aurangzeb had captured Banaras, he had ordered total destruction of all Hindu temples there. Aurangzeb then built a mosque over the ruins of this temple in 1669[182] and named it as Alamagir Mosque in the name of his own honorific title "Alamgir" which he had adopted after becoming the emperor of Mughal empire.[183][178] The mosque is located at a prominent site above the Panchganga Ghat, which is a funerary ghat facing the Ganges.[184] The mosque is architecturally a blend of Islamic and Hindu architecture, particularly because of the lower part of the walls of the mosque having been built fully with the remains of the Hindu temple.[183] The mosque has high domes and minarets.[185][178] Two of its minarets had been damaged; one minaret crashed killing a few people and the other minaret was officially brought down because of stability concerns.[178] Non-Muslims are not allowed to enter the mosque.[186] The mosque has a security cordon of a police force.[187]

Shri Guru Ravidass Janam Asthan

Shri Guru Ravidass Janam Asthan, at Sir Gobardhan is the ultimate place of pilgrimage or religious headquarters for followers of the Ravidassia religion.[188] The foundation stone was laid on 14 June 1965 on Ashad Sankranti day at the birthplace of Ravidas. The temple was completed in 1994.[189]

Sarnath

Sarnath is located 10 kilometres north-east of Varanasi near the confluence of the Ganges and the Varuna rivers in Uttar Pradesh, India.

The deer park in Sarnath is where Gautama Buddha first taught the Dharma, and where the Buddhist Sangha came into existence through the enlightenment of Kondanna,[190] as described by the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta.

The city is mentioned by the Buddha as one of the four places of pilgrimage which his devout followers should visit.[191]

Culture

Literature

Renowned Indian writers who have resided in the city were Kabir, Ravidas, and Tulsidas, who wrote much of his Ram Charit Manas here. Kulluka Bhatt wrote the best known account of Manusmriti in Varanasi in the 15th century.[citation needed] Later writers of the city have included Acharya Shukla, Baldev Upadhyaya, Bharatendu Harishchandra, Devaki Nandan Khatri, Premchand, Hazari Prasad Dwivedi, Jaishankar Prasad, Kshetresa Chandra Chattopadhyaya, Sudama Pandey (Dhoomil), Vagish Shastri, and Vidya Niwas Mishra.[citation needed]

Several newspapers and journals are or were published in Varanasi such as Varanasi Chandroday and its successor Kashivartaprakashika, which became a weekly journal, first published on 1 June 1851.[192] The main newspaper is Aj, a Hindi-language nationalist newspaper first published in 1920.[193] The newspaper was the bulwark of the Indian National Congress and is a major newspaper of Hindi northern India.[193]

Art

Varanasi is a major centre of arts and designs. It is a producer of silks and brocades with gold and silver thread work, carpet weaving, wooden toys, bangles made of glass, ivory work, perfumes, artistic brass and copper ware and a variety of handicrafts.[194][195] The cantonment graveyard of the British Raj is now the location of Varanasi's Arts and Crafts.[196]

Notable artists (musicians and dancers) and historians who are connected with the city include Thakur Jaidev Singh, Mahadev Prasad Mishra, Bismillah Khan, Ravi Shankar, Girija Devi, Gopal Shankar Misra, Gopi Krishna, Kishan Maharaj, Lalmani Misra, Premlata Sharma, N. Rajam, Siddheshwari Devi, Samta Prasad, Sitara Devi,[197] Chhannulal Mishra, Rajan Sajan Mishra, Ritwik Sanyal, Soma Ghosh, Devashish Dey, Ramkrishna Das and Harish Tiwari.

Music

Varanasi's music tradition is traced to the Pauranic days. According to ancient legend, Shiva is credited with evolving music and dance forms. During the medieval era, Vaishnavism, a Bhakti movement, grew in popularity, and Varanasi became a thriving centre for musicians such as Surdas, Kabir, Ravidas, Meera and Tulsidas. During the monarchic rule of Govind Chandra in the 16th century, the Dhrupad style of singing received royal patronage and led to other related forms of music such as Dhamar, Hori, and Chaturang. Presently the Dhrupad maestro Pandit Ritwik Sanyal from Varanasi is working for the revival of this art-music.[198]

In recent times, Girija Devi, the native famous classical singer of thumris, was widely appreciated and respected for her musical renderings.[199] Varanasi is also associated with many great instrumentalists such as Bismillah Khan[198] and Ravi Shankar, the famous sitar player and musicologist who was given the highest civilian award of the country, the Bharat Ratna.[200] Varanasi has joined the global bandwagon of UNESCO "Cities of Music" under the Creative Cities Network.[201]

Festivals

On Maha Shivaratri (February), a procession of Shiva proceeds from the Mahamrityunjaya Temple to the Kashi Vishwanath Temple.[71] Dhrupad Mela is a five-day musical festival devoted to dhrupad style held at Tulsi Ghat in February–March.[202] The Sankat Mochan Hanuman Temple celebrates Hanuman Jayanti (March–April), the birthday of Hanuman. A special puja, aarti, and a public procession is organised.[203][204] Since 1923, the temple has organised a five-day classical music and dance concert festival named Sankat Mochan Sangeet Samaroh, wherein iconic artists from all parts of India are invited to perform.[71]

The Ramlila of Ramnagar is a dramatic enactment of Rama's legend, as told in Ramacharitamanasa.[69] The plays, sponsored by Kashi Naresh, are performed in Ramnagar every evening for 31 days.[69] On the last day, the festivities reach a crescendo as Rama vanquishes the demon king Ravana.[69] Kashi Naresh Udit Narayan Singh started this tradition around 1830.[69]

Chhath Puja is celebrated on the sixth day of the lunar month of Kartika (October–November).[205][206][207] The rituals are observed over four days.[208] They include holy bathing, fasting and abstaining from drinking water (vrata), standing in water, and offering prasad (prayer offerings) and arghya to the setting and rising sun.[209] Some devotees also perform a prostration march as they head for the river banks. Chhath puja is dedicated to the sun god "Surya" and his sister "Chhathi Maiya".[210] Chhath is considered as Mahaparva by the Bhojpuri people.[211] It is said that the Chhath Mahaparva was started in Varanasi.[212]

Nag Nathaiya is celebrated on the fourth lunar day of the dark fortnight of the Hindu month of Kartik (October–November). It commemorates the victory of Krishna over the serpent Kaliya. On this occasion, a large Kadamba tree (Neolamarckia cadamba) branch is planted on the banks of the Ganges so that a boy, playing the role of Krishna, can jump into the river on to the effigy representing Kaliya. He stands over the effigy in a dancing pose playing the flute, while an audience watches from the banks of the river or from boats.[213] Bharat Milap celebrates the meeting of Rama and his younger brother Bharata after the return of the former after 14 years of exile.[71] It is celebrated during October–November, a day after the festival of Vijayadashami. Kashi Naresh attends this festival in his regal attire. The festival attracts a large number of devotees.[214]

Ganga Mahotsav is a five-day music festival organised by the Uttar Pradesh Tourism Department, held in November–December. It culminates a day before Kartik Purnima, also called the Ganges festival. On this occasion the Ganges is attended by thousands of pilgrims, release lighted lamps to float in the river from the ghats.[71][202]

The primary Muslim festivals celebrated annually in the city are the Eid al-Fitr, Bakrid, mid-Sha'ban, Bara Wafat and Muharram. Additional festivals include Alvida and Chehlum. A non-religious festival observed by Muslims is Ghazi-Miyan-ka-byaha ("the marriage of Ghazi Miyan").[215][216]

Education

Historically, Varanasi has been a centre for education in India, attracting students and scholars from across the country.[217][218] Varanasi has an overall literacy rate of 80% (male literacy: 85%, female literacy: 75%).[91] It is home to a number of colleges and universities. Most notably, it is the site of Banaras Hindu University (BHU), which is one of the largest residential universities in Asia with over 20,000 students.[219] The Indian Institute of Technology (BHU) Varanasi is designated an Institute of National Importance and is one of 16 Indian Institutes of Technology. Other colleges and universities in Varanasi include Jamia-e-Imania, the Institute of Integrated Management and Technology, Mahatma Gandhi Kashi Vidyapith, Nav Sadhana Kala Kendra, Sampurnanand Sanskrit University and Sri Agrasen Kanya P.G. College. Various engineering colleges have been established in the outskirts of the city. Other notable universities and colleges include Institute of Medical Sciences, Sampurnanand Sanskrit Vishwavidyalaya, Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies, and Harish Chandra Postgraduate College. Some research oriented institutes were also established by the government such as International Rice Research Institute (IRRI),[220] Indian Institute of Vegetable Research[221] and National Seed Research and Training Centre.[222]

Varanasi also has three Kendriya Vidyalaya. Among them Kendriya Vidyalaya BHU holds the regional office of Varanasi Region of KVS and is seat of deputy commissioner. Kendriya Vidyalaya BHU is also accredited by the British Council. Other KVs are Kendriya Vidyalaya 39 GTC and Kendriya Vidyalaya DLW.[citation needed]

St. Joseph's Convent School, in Shivpur, Varanasi, was established by the Sisters of Our Lady of Providence of France as a Catholic (Christian) minority institution with the approval of the Government of Uttar Pradesh. It is an autonomous organisation under the diocese of the Bishop of Varanasi. It provides education not only to the Catholic Christian children, but also to others who abide by its rules.[223]

Another important institution is the Central Hindu School in Kamachha. This was established by Annie Besant in July 1898 with the objective of imparting secular education. It is affiliated to the Central Board of Secondary Education and is open to students of all cultures.[224][225]

Schools in Varanasi are affiliated with the Indian Certificate of Secondary Education (ICSE), the CBSE, or the Uttar Pradesh Board of Technical Education (U.P Board). The overall "state of education in Varanasi is ... not good."[226] Schools in Varanasi vary widely in quality, with private schools outperforming government schools.[226] In government schools, many teachers fail to come to class or to teach children.[226] Some government schools lack basic equipment, such as blackboards and sufficient desks and chairs for all students.[226] Private schools vary in quality, with the most expensive conducting lessons in English (seen as a key to children's success) and having computers in classrooms.[226] Pupils attending the more expensive private schools, tended to come from upper-class families.[226] Lower-cost private schools attracted children from lower-income families or those lower-income families with higher education aspirations.[226] Government schools tend to serve lower-class children with lower education aspirations.[226]

Media

Varanasi caters a lot of shooting from different film industries in India.[227] The temple town has emerged as a hub to Hindi film industry and South film industry.[228] Also, a chunk of Bhojpuri movies are shot in the city.[229] A few Bollywood movies that were shot, include Gangs of Wasseypur, Masaan, Raanjhanaa, Piku, Shubh Mangal Zyada Saavdhan and Super 30.[230][231][232][233][234] Some parts of the Hollywood movie The Curious Case of Benjamin Button were also shot.[235] Web series such as Mirzapur and Asur were also shot in temple town.[236][237]

Newspapers are widely available in Hindi and English. Aj, Hindi newspaper was established in 1920 in Varanasi.[238] Some publishers in the city are:

The city also hosts a Doordarshan Kendra, which was established in 1984 by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. In 1998, Doordarshan studio was setup.[246]

FM/AM Stations available in the city are:[247][248][249]

- Radio City 91.9 MHz

- Red FM 93.5 MHz

- BIG FM 95.0 MHz

- Radio Mirchi 98.3 MHz

- Radio Sunbeam 90.4 MHz

- AIR Vividh Bharati 100.6 MHz

- Gyan Vani 105.6 MHz

- AIR Varanasi 1242 AM

Mobile apps such as "InVaranasi", "Varanasi" and "LiveVNS" provide a wide range of information related to travel and local news.[250][251][252]

Sport

Basketball, cricket, and field hockey are popular sports in Varanasi.[253] The main stadium in the city is the Dr Sampurnanda Stadium (Sigra Stadium), where first-class cricket matches are held.[254] The city also caters an AstroTurf hockey stadium named, Dr. Bheemrao Ambedker National Hockey Stadium.[255]

The Department of Physical Education, Faculty of Arts of BHU offers diploma courses in Sports Management, Sports Physiotherapy, Sports Psychology and Sports Journalism.[256] Also, BHU caters sports complexes including badminton court, tennis court, swimming pool and amphitheater.[257]

Gymnastics is also popular in Varanasi, and many Indian girls practise outdoors at the ghats in the mornings which hosts akhadas, where "morning exercise, a dip in the Ganges and a visit to Lord Hanuman" forms a daily ritual.[258] Despite concerns regarding water quality, two swimming clubs offer swimming lessons in the Ganges.[259]

The Varanasi District Chess Sports Association (VDCSA) is based in Varanasi, affiliated to the regional Uttar Pradesh Chess Sports Association (UPCSA).[260]

Transport

Within the city mobility is provided by taxis, rickshaws, cycle rickshaws, and three-wheelers, but with certain restrictions in the old town area of the city.[261]

Air transport

Varanasi is served by Lal Bahadur Shastri International Airport (IATA: VNS, ICAO: VEBN), which is approximately 26 km (16 mi) from the city centre in Babatpur.[262] The airport's new terminal was inaugurated in 2010, and it was granted international airport status on 4 October 2012.[263]

Railways

Varanasi Junction, commonly known as Varanasi Cantt Railway Station, is the city's largest railway station. More than 360,000 passengers and 240 trains pass through each day.[264] Banaras railway station is also a Terminal station of Varanasi. Because of huge rush at Varanasi Junction, the railway station was developed as a high facilitated terminal. Varanasi City railway station is also one of the railway stations in Varanasi district. It is located 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) north-east of Varanasi Junction railway station. It serves as Terminal station because of heavy rush at Varanasi Junction. Pandit Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Junction railway station is also the important station in Varanasi suburban.[citation needed]

Some important express trains operating from the Varanasi Junction railway station and Manduadih railway station are: Shiv Ganga Express runs between New Delhi Junction and Manduadih station while Mahamana Express runs between Varanasi junction and New Delhi Junction; the Udhna Varanasi Express that runs between Udhna (Surat) junction and Varanasi, a distance of 1,398 kilometres (869 mi);[265] the Kashi Vishwanath Express that runs between Varanasi and New Delhi railway station;[266] the Kanpur Varanasi InterCity express, also called Varuna express, which runs over a distance of 355 kilometres (221 mi) and connects with Lucknow (the capital city of Uttar Pradesh) and Varanasi;[267] and the Sabarmati Express which runs between Varanasi and Ahmedabad. Vande Bharat Express, a semi-high speed train was launched in the month of February in 2019 in the Delhi-Varanasi route.[268] The train reduced the time travel between the two cities by 15 per cent as compared to the Shatabdi Express.[269]

Varanasi has following railway stations within the city suburbs:[270][271]

| Station Name | Station Code | Railway Zone | Number of Platforms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Varanasi Junction

Also: Varanasi Cantt |

BSB | Northern Railway | 9 |

| Banaras Railway Station | BSBS | North Eastern Railway | 8 |

| Varanasi City Railway Station | BCY | North Eastern Railway | 5 |

| Kashi Railway Station | KEI | Northern Railway | 3 |

| Sarnath Railway Station | SRNT | North Eastern Railway | 3 |

| Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Junction | DDU | East Central Railway | 8 |

| Shivpur Railway Station | SOP | Northern Railway | 3 |

| Bhulanpur Railway Station | BHLP | Northern Railway/North Eastern Railway | 2 |

| Lohta Railway Station | LOT | Northern Railway | 3 |

Ropeway

Kashi ropeway is under construction since 2023. It will be 3.75 kilometres (2.33 mi) long and will have a maximum capacity of 3000 passengers per hour per direction.[272][111][112][273] It will cover the cantonment area to Godowlia, which will reduce travel time from 45 minutes to around 15 minutes.[274]

Roads

Auto rickshaws and E-rickshaws are the most widely available forms of public transport in the old city.[275] In the outer regions of the city, taxis are available.[275] Daily commuters prefer city buses, which operate on specific routes of urban and suburban areas. The city buses are operated by Varanasi City Transport Service Limited.[276] Nearly, 120 buses are operated by Varanasi City Transport Service Limited.[277]

The following National Highways pass through Varanasi:[278][279][280][281][282]

| National Highway | Route | Total Length |

|---|---|---|

| NH 19 | Delhi » Mathura » Agra » Kanpur » Prayagraj » Varanasi » Mohania » Barhi » Palsit » Kolkata | 1,323 km (822 mi) |

| NH 233 | Varanasi » Azamgarh » Tanda » Basti » Siddharthnagar » Lumbini (Nepal) | 288 km (179 mi) |

| NH 35 | Mahoba » Banda » Chitrakoot » Prayagraj » Mirzapur » Varanasi | 346 km (215 mi) |

| NH 31 | Unnao » Raebareli » Pratapgarh » Varanasi » Patna » Samsi | 968 km (601 mi) |

| NH 7 | Varanasi » Jabalpur » Nagpur » Hyderabad » Bangalore » Kanyakumari | 2,369 km (1,472 mi) |

The heavy traffic of the city is monitored through Integrated Traffic Management System. The smart traffic management system equips the city with automatic signal control system, separate signal system for pedestrians, traffic management centre at state level, area traffic control system, corridor management and dynamic traffic indicators for smooth movement of traffic.[283] Varanasi Traffic Police keeps an eye through Smart Command and Control Centre.[284][285]

Inland waterways

National Waterway 1 passes through Varanasi. In 2018, a new inland port was established on the banks of Ganges River.[286] The Multi-Modal Terminal is designed to handle 1.26 million metric tons of cargo every year and covers an area of 34 hectares.[287] Nearly, ₹170 crore was invested by the government to set up an inland port.[288] Maersk started its container service in 2019 by moving 16 containers on NW-1 from Varanasi to Kolkata. The port also catered PepsiCo, IFFCO Fertilizers, Emami Agrotech and Dabur for cargo movement.[289]

Projects

Due to growing population and industrial demands, the city is being implanted with several infrastructural projects.[290] In fiscal year 2014–18, the city was awarded with projects worth ₹30,000 crore.[291] The city is being invested by both private and public players in different sectors.[292] There are many undergoing projects and many have been planned.[citation needed]

Road

The government is executing seven road projects connecting Varanasi, the total project cost being ₹7,100 crore (US$850 million) and the total length of the project being 524 kilometres (326 mi).[citation needed] Some important projects are:

- Six lane Varanasi-Aurangabad section of NH-19[293]

- Six lane Varanasi-Allahabad NH-19[294]

- Four lane Varanasi-Gorakhpur NH-29[295]

- Ghagra Bridge-Varanasi section of NH-233[293]

- Four lane Varanasi-Azamgarh Section NH-233[296]

- Four lane Varanasi-Sultanpur NH-56[297]

- New four lane Varanasi-Ayodhya Highway[298]

- Varanasi Ring Road Phase – 2[299]

- Ganga Expressway Phase – 2[300]

- Varanasi-Ranchi-Kolkata Greenfield Expressway[301]

- Purvanchal Link Expressway[302]

Railways

In 2018, the budget reflected undergoing rail projects of worth ₹4,500 crore (US$540 million). Some important projects are:[303]

- 3rd rail line between Varanasi-Mughalsarai[304]

- New Delhi-Varanasi High Speed Rail Corridor[305]

- Eastern Dedicated Freight Corridor (Jeonathpur Railway Station)[306]

- Kashi Railway Station to be developed as Intermodal Station (IMS)[307][308]

Airport

- Extension of runway by 1325 meters (First of its kind: National Highway under the airport runway)[309]

- New terminal with passenger capacity of 4.5 million per year[310]

Metro

The Varanasi Metro is a rapid transit proposed for Varanasi. The proposed system consists of two lines, spanning from BHEL to Banaras Hindu University (19.35 kilometres (12.02 mi)) and Benia Bagh to Sarnath (9.885 kilometres (6.142 mi)). The feasibility study of the project was done by RITES and was completed in June 2015. There will be 26 stations, including 20 underground and six elevated on the two lines, which includes total length of 29.235 kilometres (18.166 mi) consisting of 23.467 kilometres (14.582 mi) underground, while 5.768 kilometres (3.584 mi) will be elevated.[311][312][313][314] The total estimated completion cost for construction of Varanasi Metro is estimated to be ₹13,133 crore (US$1.6 billion).[315]

Commercial

- Rudraksha Convention Centre[316]

- Kashi Vishwanath Corridor[317]

- 100 acres (40 ha) freight village for multimodal terminal[318]

- Film city to be developed in area of 106 acres (43 ha)[319]

- Bus terminal cum shopping mall[320][321]

- IT Park[322]

- Textile Park[323][324]

- Integrated Commissioner Complex (ICC) twin towers[325]

Sister cities

| Country | City |

|---|---|

| Kyoto[326][327] | |

| Kathmandu[328][329] |

See also

Gallery

-

Horse on the Varanasi Beach

-

Boat ride on the Ganges River

-

A cow walking down the street

-

Monkey

-

Goat

References

Notes

Citations

- ^ a b Varanasi City:

—"Census of India: Varanasi M. Corp". censusindia.gov.in. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

—"Census of India: Varanasi CB". censusindia.gov.in. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021. - ^ Dikshit, Rajeev (13 May 2023). "In Varanasi BJP's Ashok Tiwari defeats SP by 1.33L votes". The Times of India. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ "Varanasi City". 7 January 2022. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ "District Census Handbook Varanasi" (PDF). censusindia.gov.in. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ^ "Urban Agglomerations/Cities having population 1 lakh and above" (PDF). Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ a b "52nd Report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India" (PDF). nclm.nic.in. Ministry of Minority Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- ^ "Yogi Adityanath is right. Route to UP's $1 trillion GDP goal passes through hinterland". Retrieved 25 September 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Executive Summary" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 August 2019. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ "Slum Free City Plan of Action Varanasi" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 June 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ Chaurasia, Aalok Ranjan (26 July 2023). "Human Development in Districts of India 2019–2021". Indian Journal of Human Development. 17 (2): 219–252. doi:10.1177/09737030231178362. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ San Chirico, Kerry P. C. (2012), "Banaras", in Juergensmeyer, Mark; Roof, Wade Clark (eds.), Encyclopedia of Global Religion, Volume 1, pp. 114–116, ISBN 9780761927297,

Varanasi is the city's revived, post-independence designation, which combines the names of two rivers on either side of it.

- ^ "Varanasi", Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1 September 2021, retrieved 14 December 2021,

Varanasi, also called Benares, Banaras, or Kashi, city, southeastern Uttar Pradesh state, northern India.

- ^ San Chirico, Kerry P. C. (2012). "Banaras". In Juergensmeyer, Mark; Roof, Wade Clark (eds.). Encyclopedia of Global Religion. Vol. 1. pp. 114–116. ISBN 9780761927297.

The city was identified in the Pali language as Baranasi, from which emerged the corrupt form of the name, 'Banaras', by which the city is still widely known.

- ^ "Benares" is the name that appears in the 1909 official map of India.

- ^ a b San Chirico, Kerry P. C. (2012). "Banaras". In Juergensmeyer, Mark; Roof, Wade Clark (eds.). Encyclopedia of Global Religion. Vol. 1. pp. 114–116. ISBN 9780761927297.

... in the fifth century BCE, ... the Kingdom of Kashi was one of the 16 kingdoms to emerge from the ascendant Aryan tribes.

- ^ *Fouberg, Erin H.; Moseley, William G. (2018), Understanding World Geography, New York: John Wiley & Sons, p. 173, ISBN 9781119473169, OCLC 1066742384,

The city of Varanasi, India, is central to the death tradition in Hinduism. Hindus see Varanasi as the world of death and life, and some make pilgrimages to Varanasi to die. In Hindu tradition, if a person dies in the holy city of Varanasi on the Ganges River, he or she is attains moksha, or freedom from the cycle of death and rebirth. Pilgrims travel to Varanasi to cremate their deceased relatives on the ghats along the river.

- Eck, Diana (2013) [1981], Banaras, the City of Light, Alfred Knopf Inc, [Columbia University Press], p. 324,

–No other city on earth is as famous for death as is Banāras. More than for her temples and magnificent ghāts, more than for her silks and brocades, Banāras, the Great Cremation Ground, is known for death. At the centre of the city along the riverfront is Manikarnikā, the sanctuary of death, with its ceaselessly smoking cremation pyres. The burning ghāt extends its influence and the sense of its presence throughout the city.

- Parry, Jonathan P. (2000) [1994], Death in Banaras, Lewis Henry Morgan Lectures, Cambridge University Press, p. 1, ISBN 9780521466257,

As a place to die, to dispose of the physical remains of the deceased and to perform the rites which ensure that the departed attains a 'good state' after death, the north Indian city of Banaras attracts pilgrims and mourners from all over the Hindu world.

- Singh, Ravi Nandan (2022). Dead in Banaras: An Ethnography of Funeral Travelling. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

The present-day Banaras, at first sign, is a new place. Rightly so, the baton must then pass on to an all new chronicling of the place. Yet, a connecting link, as always, may come into play, between the book's time and other times of Banaras. Let me give an example of what such a connection might look like. Jonathan Parry (1994) in his classic Death in Banaras laments in the preface to the book that he could not incorporate the coming in of the electric crematorium in his descriptions of the funerary organization in Banaras. Two decades later into my fieldwork, I found that it is in part, the efficiency of the open-air, manual cremation that Parry so effectively captures in his book that explains how a promising symbol of industrial modernity, the electric crematorium, falls short of the typecast. In the years between his book and my fieldwork, the electric crematorium sat lonely and was sparingly used against the cheer of the always-on, busy, manual pyres whose flames continue to dot the scene of the ghats in a contrasting relief. In this above sense, I believe, Parry already provides us a portrait of the electric crematorium's social imaginary in Banaras. The question of the shift from wooden pyres to the electric crematorium is then not about competing technologies but that of ethics with which the dead are tended to amidst the assemblies of funeral travellers.

- Eck, Diana (2013) [1981], Banaras, the City of Light, Alfred Knopf Inc, [Columbia University Press], p. 324,

- ^ Garces-Foley, Kathleen (2022), "At the Intersection of Death and Religion", in Garces-Foley, Kathleen (ed.), Death and Religion in a Changing World (2 ed.), London and New York: Routledge, p. 186, doi:10.4324/9781003126997, ISBN 978-0-367-64930-2,

It is not uncommon for immigrants to discover that their long-established death practices are deemed unacceptable by civil authorities in their new home. We see this for example in the experiences of Sikhs and Hindus living in Sweden and the United States where open cremation pyres are not permitted. Market forces and social context also shape religious practices by limiting access to some goods and services while promoting others and offering new possibilities for action. ... The logistical difficulty of transporting a body from the United States or the UK to the auspicious city of Varanasi, India, for cremation is surmounted by entrepreneurial service providers who manage the process for Hindu customers.

- ^ Arnold, David (2021), Burning the Dead: Hindu Nationhood and the Global Construction of Indian Tradition, Oakland: University of California Press, p. 11, ISBN 9780520379343, LCCN 2020026923,

While Benares is undeniably central to the performance and perception of modern Indian cremation, that history cannot be told from Benares alone. Rather, ... the narrative needs to encompass colonial India's two main metropolises, Bombay (Mumbai) and Calcutta (Kolkata), as well as the movement of Indians overseas and their memorialization abroad. ... The history of cremation in India is far more than the history of traditional rites and practices that it is conventionally taken to be—if tradition is assumed to mean "timeless" custom and immutable belief. On the contrary, cremation in modern India and across the South Asian diaspora is a history of contestation and change, of longing and denial, adaptation and innovation. India, too, has gifted to the world a modern cremation movement, though its meaning, form, and global resonance necessarily differed substantially from the Western cremation movement with which it was nearly contemporaneous.

- ^ *Williams, Philippa (17 January 2019). "Working Narratives of Intercommunity Harmony in Varanasi's Silk Sari Industry". In Jeffrey, Roger; Jeffrey, Craig; Lerche, Jens (eds.). Development Failure and Identity Politics in Uttar Pradesh. SAGE. pp. 211–238. ISBN 978-81-321-1663-9.

'Varanasi … is the city where Hindus and Muslims … are interwoven like threads as in the lovely silk saris for which Kashi (Varanasi) is so famous for (Puniyani, 2006).'(quoted) Varanasi is most often represented as a sacred Hindu pilgrimage centre (see Eck, 1983), as its social and cultural urban spaces have been often examined through the imagined and lived realities of Hinduism (Hertel and Humes, 1993; Parry, 1994; Singh and Rana, 2002). But it is also home to a sizeable Muslim population, which in 2001 comprised 30 per cent of the city's residents, significantly more than the percentage of Muslims in UP (Census of India, 2001). Unlike the city's majority Hindu inhabitants (63 per cent), who occupy a range of occupations in different economic sectors, Muslims in the city are predominantly involved in the production of silk fabrics, as well as other smaller artisanal industries (see Kumar, 1988). Muslims first settled in Varanasi in the eleventh century, when, following the defeat of an invading Muslim army, women, children and civilians were permitted to remain on the northern side of the city and serve the Hindu kings. Many learned the craft of weaving, incorporating their skills and designs into the fabrics. Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, the French explorer and cultural anthropologist, visited Varanasi between 1660 and 1665 and reported that in the courtyard of a rest house in the Chowk area the trading of reshmi (silk) and suti (cotton) fabrics was taking place between Muslim karigars (artisans or craftsmen) and Hindu Mahajans (traders)

- Puniyani, Ram (21 April 2006), "Tackling Terrorism – Varanasi, Jama Masjid Show the Way", CounterCurrents.Org,