Chris Benoit

| Chris Benoit | |

|---|---|

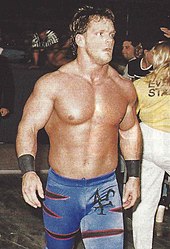

Benoit in February 2006 | |

| Birth name | Christopher Michael Benoit |

| Born | May 21, 1967 Montreal, Quebec, Canada |

| Died | June 24, 2007 (aged 40) Fayetteville, Georgia, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Suicide by hanging |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 3 (2 living; 1 died 2007) |

| Professional wrestling career | |

| Ring name(s) | Chris Benoit The Pegasus Kid Wild Pegasus |

| Billed height | 5 ft 11 in (180 cm)[1] |

| Billed weight | 229 lb (104 kg)[1] |

| Billed from | Atlanta, Georgia Edmonton, Alberta, Canada |

| Trained by | Bruce Hart[2][3][4] Stu Hart Mike Hammer Tokyo Joe Tatsumi Fujinami New Japan Pro-Wrestling[5] |

| Debut | November 22, 1985[6] |

Christopher Michael Benoit (/bəˈnwɑː/ bə-NWAH; May 21, 1967 – June 24, 2007) was a Canadian professional wrestler. He worked for various pro-wrestling promotions during his 22-year career, but is notorious for murdering his wife and youngest son.

Bearing the nicknames The (Canadian) Crippler alongside The Rabid Wolverine throughout his career, Benoit held 30 championships between World Wrestling Federation/World Wrestling Entertainment (WWF/WWE), World Championship Wrestling (WCW), Extreme Championship Wrestling (ECW – all United States), New Japan Pro-Wrestling (NJPW – Japan), and Stampede Wrestling (Canada). He was a two-time world champion, Benoit having reigned as a one-time WCW World Heavyweight Champion and a one-time World Heavyweight Champion in WWE;[7][8] he was booked to win a third world championship at a WWE event on the night of his death.[9] Benoit was the twelfth WWE Triple Crown Champion and the seventh WCW Triple Crown Champion, and the second of four men in history to achieve both the WWE and the WCW Triple Crown Championships. He was also the 2004 Royal Rumble winner, joining Shawn Michaels and preceding Edge as one of the three men to win a Royal Rumble as the number one entrant.[10] Benoit headlined multiple pay-per-views for World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE) including a victory in the World Heavyweight Championship main event triple threat match of WrestleMania XX in March 2004.[11]

In a three-day double-murder and suicide, Benoit murdered his wife in their residence on June 22, 2007, and his 7-year-old son the next day, before killing himself on June 24.[12][13] The incident profoundly shocked and changed the professional wrestling industry and drew intense mainstream media criticism regarding brain injuries, substance abuse, and the long-term health of athletes in contact sports. Subsequent research undertaken by the Sports Legacy Institute (now the Concussion Legacy Foundation) suggested that depression and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a condition of brain damage, from multiple concussions that Benoit had sustained throughout his pro-wrestling career were likely contributing factors of the crimes.[14]

Due to his murders, Benoit's legacy in the professional wrestling industry is heavily debated.[15][16] Benoit has been renowned by many for his exceptional technical wrestling ability. Prominent combat sports journalist Dave Meltzer considers Benoit "one of the top 10, maybe even [in] the top five, all-time greats" in professional wrestling history.[17] Benoit was inducted into the Stampede Wrestling Hall of Fame in 1995 and the Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame in 2003.[18] His WON induction was put to a re-vote in 2008 to determine if Benoit should remain a member of their Hall of Fame. The threshold percentage of votes required to remove Benoit was not met.[19]

Early life

Benoit was born in Montreal, Quebec, the son of Michael and Margaret Benoit. He grew up in Edmonton, Alberta, from where he was billed throughout the bulk of his career.[14] He had a sister who lived near Edmonton.[20]

During his childhood and early adolescence in Edmonton, Benoit idolized Tom "Dynamite Kid" Billington[21][22] and Bret Hart;[22][23] at twelve years old, he attended a local wrestling event at which the two performers "stood out above everyone else".[21] Benoit trained to become a professional wrestler in the Hart family "Dungeon", receiving education from family patriarch Stu Hart. In-ring, Benoit emulated both Billington and Bret Hart,[21][23] cultivating a high-risk style and physical appearance more reminiscent of the former[21] (years later, he adopted Hart's own "Sharpshooter" hold as a finishing move).[citation needed]

Professional wrestling career

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2016) |

Stampede Wrestling (1985–1989)

Benoit began his career in 1985, in Stu Hart's Stampede Wrestling promotion. From the beginning, similarities between Benoit and Billington were apparent, as Benoit adopted many of his moves such as the diving headbutt and the snap suplex; the homage was complete with his initial billing as "Dynamite" Chris Benoit. According to Benoit, in his first match, he attempted the diving headbutt before learning how to land correctly, and had the wind knocked out of him; he said he would never do the move again at that point. His debut match was a tag team match on November 22, 1985, in Calgary, Alberta, where he teamed with "The Remarkable" Rick Patterson against Butch Moffat and Mike Hammer, which Benoit's team won the match after Benoit pinned Moffat with a sunset flip.[6] The first title Benoit ever won was the Stampede British Commonwealth Mid-Heavyweight Championship on March 18, 1988, against Gama Singh.[24] During his tenure in Stampede, he won four International Tag Team and three more British Commonwealth titles,[25] and had a lengthy feud with Johnny Smith that lasted for over a year, which both men traded back-and-forth the British Commonwealth title. In 1989, Stampede closed its doors, and with a recommendation from Bad News Allen, Benoit departed for New Japan Pro-Wrestling.

New Japan Pro-Wrestling (1986–1999)

Upon arriving to New Japan Pro-Wrestling (NJPW), Benoit spent about a year training in their "New Japan Dojo" with the younger wrestlers to improve his abilities. While in the dojo, he spent months doing strenuous activities like push-ups and floor sweeping before stepping into the ring. He made his Japanese debut in 1986 under his real name. In 1989, he started wearing a mask and assuming the name The Pegasus Kid. Benoit said numerous times that he originally hated the mask, but it eventually became a part of him. While with NJPW, he came into his own as a performer in critically acclaimed matches with luminaries like Jushin Thunder Liger, Shinjiro Otani, Black Tiger, and El Samurai in their junior heavyweight division.[citation needed]

In August 1990, he won his first major championship, the IWGP Junior Heavyweight Championship, from Jushin Thunder Liger. He eventually lost the title in November 1990 (and in July 1991 in Japan and in November 1991 in Mexico, his mask) back to Liger,[25] forcing him to reinvent himself as Wild Pegasus. Benoit spent the next couple years in Japan, winning the Best of the Super Juniors tournament twice in 1993 and 1995. He went on to win the inaugural Super J-Cup tournament in 1994, defeating Black Tiger, Gedo, and The Great Sasuke in the finals. He wrestled outside New Japan occasionally to compete in Mexico and Europe, where he won a few regional championships, including the UWA Light Heavyweight Championship. He held that title for over a year, having many forty-plus minute matches with Villano III.[citation needed]

World Championship Wrestling (1992–1993)

Benoit first came to World Championship Wrestling (WCW) in June 1992, teaming up with fellow Canadian wrestler Biff Wellington for the NWA World Tag Team Championship tournament; they were defeated by Brian Pillman and Jushin Thunder Liger in the first round at Clash of the Champions XIX.

He did not return to WCW until January 1993 at Clash of the Champions XXII, defeating Brad Armstrong. A month later, at SuperBrawl III, he lost to 2 Cold Scorpio, getting pinned with only three seconds left in the 20-minute time limit. At the same time, he formed a tag team with Bobby Eaton. After he and Eaton lost to Scorpio and Marcus Bagwell at Slamboree, Benoit headed back to Japan.

Various promotions (1993–1994)

After WCW, Benoit worked in Australia, and CMLL in Mexico. In early 1994, he worked for NWA New Jersey where he defeated Jerry Lawler. A month later he fought Terry Funk to a double count out.

Extreme Championship Wrestling (1994–1995)

In August 1994, Benoit began working with Extreme Championship Wrestling (ECW) in between tours of Japan. He was booked as a dominant wrestler there, gaining notoriety as the "Crippler" after he put Rocco Rock out. In his first appearance, Benoit competed in a one-night eight-man tournament for the vacant NWA World Heavyweight Championship, losing to 2 Cold Scorpio in the quarter-finals match.[26][27]

At November to Remember, Benoit accidentally broke Sabu's neck within the opening seconds of the match. The injury came when Benoit threw Sabu with the intention that he take a face-first "pancake" bump, but Sabu attempted to turn mid-air and take a backdrop bump instead. He did not achieve full rotation and landed almost directly on his neck.[28]

After this match Benoit returned to the locker room and broke down over the possibility that he might have paralysed someone.[28] Paul Heyman, the head booker of ECW at the time, came up with the idea of continuing the "Crippler" moniker for Benoit. From that point until his departure from ECW, he was known as "Crippler Benoit". When he returned to WCW in October 1995, WCW modified his ring name to "Canadian Crippler Chris Benoit". In The Rise and Fall of ECW book, Heyman commented that he planned on using Benoit as a dominant heel for quite some time, before putting the company's main title, the ECW World Heavyweight Championship, on him to be the long-term champion of the company.

Benoit and Dean Malenko won the ECW World Tag Team Championship – Benoit's first American title – from Sabu and The Tazmaniac in February 1995 at Return of the Funker.[25] After winning, they were initiated into the Triple Threat stable, led by ECW World Heavyweight Champion, Shane Douglas, as Douglas's attempt to recreate the Four Horsemen, as the three-man contingency held all three of the ECW championships at the time (Malenko also held the ECW World Television Championship at the time). The team lost the championship to The Public Enemy that April at Three Way Dance. Benoit spent some time in ECW feuding with The Steiner Brothers and rekindling the feud with 2 Cold Scorpio. He was forced to leave ECW after his work visa expired; Heyman was supposed to renew it, but he failed to make it on time, so Benoit left ECW in August 1995 as a matter of job security and the ability to enter the United States. He toured Japan until WCW called.[25]

World Wrestling Federation (1995)

In June 1995, while under contract with ECW, Benoit worked in three dark matches losing to Bob Holly, Adam Bomb and Owen Hart.[29]

Return to WCW (1995–2000)

The Four Horsemen (1995–1999)

New Japan Pro-Wrestling (NJPW) and World Championship Wrestling (WCW) had a working relationship, and because of their "talent exchange" program, Benoit signed with WCW in late 1995 along with a number of talent working in New Japan to be a part of the angle. Like the majority of those who came to WCW in the exchange, he started out in as a member of the cruiserweight division, having lengthy matches against many of his former rivals in Japan on almost every single broadcast. At the end of 1995, Benoit went back to Japan as a part of the "talent exchange" to wrestle as a representative for New Japan in the Super J-Cup: 2nd Stage, defeating Lionheart in the quarterfinals (he received a bye to the quarterfinals for his work in 1995, similar to the way he advanced in the 1994 edition) and losing to Gedo in the semifinals.

After impressing higher-ups with his work, he was approached by Ric Flair and the WCW booking staff to become a member of the reformed Four Horsemen in 1995, alongside Flair, Arn Anderson, and Brian Pillman; he was introduced by Pillman as a gruff, no-nonsense heel similar to his ECW persona, "The Crippler". He was brought in to add a new dynamic for Anderson and Flair's tormenting of Hulk Hogan and Randy Savage in their "Alliance to End Hulkamania", which saw the Horsemen team up with The Dungeon of Doom, but that alliance ended with Dungeon leader and WCW booker, Kevin Sullivan feuding with Pillman. When Pillman abruptly left the company for the WWF, Benoit was placed into his ongoing feud with Sullivan. This came to fruition through a dissension between the two in a tag team match with the two reluctantly teaming with each other against The Public Enemy, and Benoit being attacked by Sullivan at Slamboree. This led to the two having violent confrontations at pay-per-views, which led to Sullivan booking a feud in which Benoit was having an affair with Sullivan's real-life wife and onscreen valet, Nancy (also known as Woman). Benoit and Nancy were forced to spend time together to make the affair look real, (hold hands in public, share hotel rooms, etc.).[30]

This onscreen relationship developed into a real-life affair offscreen. As a result, Sullivan and Benoit had a contentious backstage relationship at best, and an undying hatred for each other at worst. Benoit did, however, admit having a certain amount of respect for Sullivan, saying on the DVD Hard Knocks: The Chris Benoit Story that Sullivan never took undue liberties in the ring during their feud, even though he blamed Benoit for breaking up his marriage. This continued for over the course of a year with Sullivan having his enforcers apprehend Benoit in a multitude of matches. This culminated in a retirement match at the Bash at the Beach, where Benoit defeated Sullivan; this was used to explain Sullivan going to a behind-the-scenes role, where he could focus on his initial job of booking.

In 1998, Benoit had a long feud with Booker T. They fought over the WCW World Television Championship until Booker lost the title to Fit Finlay.[25] Booker won a "Best-of-Seven" series which was held between the two to determine a number one contender. Benoit went up 3 to 1 before Booker caught up, forcing the 7th and final match on Monday Nitro. During the match, Bret Hart interjected himself, interfering on behalf of Benoit in an attempt to get him to join the New World Order. Benoit refused to win that way and told the referee what happened, getting himself disqualified. Booker refused that victory, instead opting for an eighth match at the Great American Bash to see who would fight Finlay later that night. Booker won the final match and went on to beat Finlay for the title.[25] This feud significantly elevated both men's careers as singles competitors, and both remained at the top of the midcard afterward.

In 1999, Benoit teamed with Dean Malenko once again and defeated Curt Hennig and Barry Windham to win the WCW World Tag Team Championship.[25] This led to a reformation of the Four Horsemen with the tag team champions, Anderson, and Steve "Mongo" McMichael. The two hunted after the tag team championship for several months, feuding with teams like Raven and Perry Saturn or Billy Kidman and Rey Mysterio Jr.

The Revolution and World Heavyweight Champion (1999–2000)

After a falling out with Anderson and McMichael, Benoit and Malenko left the Horsemen; he won the WCW United States Heavyweight Championship[25] before bringing together Malenko, Perry Saturn, and Shane Douglas to form "the Revolution".

The Revolution was a heel stable of younger wrestlers who felt slighted (both kayfabe and legitimate) by WCW management, believing they never gave them the chance to be stars, pushing older, more established wrestlers instead, despite their then-current questionable worthiness of their pushes. This led to the Revolution seceding from WCW, and forming their own nation, complete with a flag. This led to some friction being created between Benoit and leader, Douglas, who called into question Benoit's heart in the group, causing Benoit to quit the group, thus turning face, and having his own crusade against the top stars, winning the Television title one more time and the United States title from Jeff Jarrett in a ladder match. In October 1999 on Nitro in Kansas City, Missouri, Benoit wrestled Bret Hart as a tribute to Bret's brother Owen Hart, who had recently died due to an equipment malfunction. Hart defeated Benoit by submission, and the two received a standing ovation, and an embrace from guest ring announcer, Harley Race.

Benoit was unhappy working for WCW.[31] One last attempt in January 2000 was made to try to keep him with WCW, by putting the vacant WCW World Heavyweight Championship on him by defeating Sid Vicious at Souled Out.[25][32] However, due to disagreements with management and to protest the promotion of Kevin Sullivan to head booker,[33] Benoit left WCW the next day alongside his friends Eddie Guerrero, Dean Malenko, and Perry Saturn, forfeiting his title in the process.[31] WCW then refused to acknowledge Benoit's victory as an official title reign, and Benoit's title reign was not listed in the title lineage at WCW.com.[34] However, the WWF recognized Benoit's title win, and Benoit's title reign is still listed in the title lineage at WWE.com.[35] Benoit spent the next few weeks in Japan before heading to the WWF, who acknowledged his WCW World Heavyweight Championship win and presented him as a former world champion.[36]

World Wrestling Federation/Entertainment (2000–2007)

The Radicalz and teaming with Chris Jericho (2000–2001)

Benoit joined the World Wrestling Federation near the end of its Attitude Era. Along with Guerrero, Saturn and Malenko, he debuted in the WWF as a stable that became known as the Radicalz. After losing their "tryout matches" upon entry, The Radicalz aligned themselves with WWF Champion Triple H and became a heel faction. Benoit quickly won his first title in the WWF just over a month later at WrestleMania 2000 on April 2, pinning Chris Jericho in a triple threat match to win Kurt Angle's Intercontinental Championship. It was also in this time period that Benoit wrestled in his first WWF pay-per-view main events, challenging The Rock for the WWF Championship at Fully Loaded on July 23 and as part of a fatal four-way title match at Unforgiven on September 24. On both occasions Benoit appeared to have won the title, only to have the decision reversed by then-WWF commissioner Mick Foley due to cheating on Benoit's part. Benoit simultaneously entered into a long-running feud with Jericho for the Intercontinental title, with the two meeting at Backlash on April 30, Judgment Day on May 21 and SummerSlam on August 27; Benoit winning all three matches. The feud finally culminated in Jericho defeating Benoit in a ladder match at the Royal Rumble on January 21, 2001. Benoit won the Intercontinental title three times between April 2000 and January 2001.[37]

In early 2001, Benoit broke away from The Radicalz (who had recently reformed three months earlier) and turned face, feuding first with his former stablemates and then with Kurt Angle, whom he wrestled and lost to at WrestleMania X-Seven on April 1.[38] He gained some amount of revenge after beating Angle in an "Ultimate Submission" match at Backlash on April 29. The feud continued after Benoit stole Angle's cherished Olympic Gold Medal. This culminated in a match at Judgment Day on May 20 where Angle won a two out of three falls match with the help of Edge and Christian. In response, Benoit teamed up with his former rival Jericho to defeat Edge and Christian in that night's Tag Team Turmoil match to become the number one contenders to the WWF Tag Team Championship.

The next night on Raw Is War, Benoit and Jericho defeated Stone Cold Steve Austin and Triple H to win the WWF Tag Team Championship. On the May 24 episode of SmackDown!, Benoit suffered a legitimate neck injury in a four-way TLC match. Benoit challenged Austin for the WWF Championship on two occasions, first losing in a manner similar to the Montreal Screwjob in Calgary on the May 28 episode of Raw is War and then losing in a close match in Benoit's hometown of Edmonton on the May 31 episode of SmackDown!. Despite the neck injury, he continued to wrestle until the King of the Ring on June 24, where he was pinned by Austin in a triple threat match for the WWF Championship also involving Jericho. Benoit missed the next year due to his neck injury, missing the entire Invasion storyline.

Championship pursuits and reigns (2002–2003)

During the first WWF draft, he was the third wrestler picked by Vince McMahon to be part of the new SmackDown! roster,[39] although still on the injured list. However, when he returned, he did so as a member of the Raw roster. On his first night back, he turned heel by aligning himself with Eddie Guerrero, and he feuded with Stone Cold Steve Austin briefly.[40] Benoit defeated Rob Van Dam on the July 29, 2002, edition of Raw to become Intercontinental Champion for the fourth and final time. He and Guerrero were then moved to SmackDown! during a storyline "open season" on wrestler contracts,[41] with Benoit taking the Intercontinental Championship to SmackDown!.[42] Van Dam defeated Benoit at SummerSlam on August 25 and returned the title to Raw.[43][44]

After returning to SmackDown!, he embarked on a feud with Kurt Angle in which he defeated him at Unforgiven on September 22. On October 20, 2002, at No Mercy, he teamed with Angle to win a tournament to crown the first-ever WWE Tag Team Champions.[43][45] They became tweeners after betraying Los Guerreros. At Rebellion, Benoit and Angle made their successful title defence, defeating Los Guerreros. They lost the championships to Edge and Rey Mysterio on the November 7 episode of SmackDown! in a two-out-of-three falls match. They received a rematch at Survivor Series on November 17 in a triple threat elimination match against Edge and Mysterio and Los Guerreros, but failed to win the titles after being the first team eliminated.[46] The team split up shortly afterward and Benoit became a face.[citation needed]

Angle won his third WWE Championship from Big Show at Armageddon on December 15,[47] and Benoit faced him for the title at the Royal Rumble on January 19, 2003. The match was highly praised from fans and critics. Although Benoit lost the match, he received a standing ovation for his efforts.[48] Benoit returned to the tag team ranks, teaming with the returning Rhyno.[49]

At WrestleMania XIX on March 30, the WWE Tag Team Champions, Team Angle (Charlie Haas and Shelton Benjamin), put their titles on the line against Benoit and his partner Rhyno and Los Guerreros in a triple threat tag team match. Team Angle retained when Benjamin pinned Chavo.[50]

In April 2003, following WrestleMania, Benoit then feuded with John Cena (wearing a shirt saying "Toothless Aggression") and The Full Blooded Italians,[51][52] teaming with Rhyno occasionally.[53]

In June 2003, the WCW United States Championship was reactivated and renamed the WWE United States Championship, and Benoit participated in the tournament for the title. He lost in the final match to Eddie Guerrero at Vengeance on July 27.[53] The two feuded over the title for the next month,[54] and Benoit went on to defeat the likes of A-Train at No Mercy on October 19,[55] Big Show, and eliminating Brock Lesnar by submission at Survivor Series on November 16 as part of a Survivor Series elimination tag team match between Team Angle against Team Lesnar. As a result, Benoit challenged Lesnar for the WWE Championship on the December 4 episode of SmackDown!, but lost after passing out to Lesnar's debuting Brock Lock submission hold.[55] SmackDown! General Manager Paul Heyman had a vendetta against Benoit along with Lesnar, preventing him from gaining a shot at Lesnar's WWE Championship.[56]

World Heavyweight Champion (2004–2005)

When Benoit won a qualifying match for the 2004 Royal Rumble against the Full Blooded Italians in a handicap match with John Cena, Heyman named him as the number one entry.[57] On January 25, 2004, he won the Royal Rumble by last eliminating Big Show, and thus earned a world title shot at WrestleMania XX on March 14.[55] He became only the second WWE performer to win the Royal Rumble as the number one entrant along with Shawn Michaels. With Benoit being on the SmackDown! brand at the time, it was assumed that he was going to compete for his brand's championship, the WWE Championship. However, Benoit exploited a "loophole" in the rules and moved to the Raw brand the following night to announce he would instead challenge World Heavyweight Champion Triple H at WrestleMania.[58] Though the match was originally intended to be a one-on-one match, Shawn Michaels, whose Last Man Standing match against Triple H at the Royal Rumble for the World Heavyweight Championship ended in a draw,[55] thought that he deserved to be in the main event. When it was time for Benoit to sign the contract putting himself in the main event, Michaels superkicked him and signed his name on the contract,[55] which eventually resulted in a Triple Threat match between Michaels, Benoit, and the champion, Triple H.[59]

At WrestleMania, Benoit won the World Heavyweight Championship by forcing Triple H to tap out to his signature submission move, the Crippler Crossface, in a highly acclaimed match.[60] The match marked the first time the main event of a WrestleMania ended in submission.[61][62] After the match, Benoit celebrated his win with then-reigning WWE Champion Eddie Guerrero. The rematch was held at Backlash on April 18 in Benoit's hometown of Edmonton. It was Michaels who ended up submitting to Benoit's Sharpshooter, allowing Benoit to retain his title.[60] The next night in Calgary on the April 19 episode of Raw, he and Edge won the World Tag Team Championship from Batista and Ric Flair, making Benoit a double champion.[63]

Following his victories, Benoit and Edge engaged in a rivalry with La Résistance for the World Tag Team Championship, which saw a series of matches (including losing the titles to La Résistance on the May 31 episode of Raw), while simultaneously having confrontations with Kane over the World Heavyweight Championship. Benoit wrestled in two matches at Bad Blood on June 13 in his respective rivalries; he and Edge failed to regain the World Tag Team Championship (winning by disqualification when Kane interfered) while he successfully defended the World Heavyweight Championship against Kane. A month later at Vengeance on July 11, Benoit retained the title against Triple H.[64]

At SummerSlam on August 15, Benoit lost the World Heavyweight Championship to Randy Orton.[65] Benoit then teamed with William Regal at Unforgiven on September 12 against Ric Flair and Batista in a winning effort. Benoit then feuded with Edge (who had turned into an arrogant and conceited heel), leading to Taboo Tuesday on October 19 where Benoit, Edge, and Shawn Michaels were all put into a poll to see who would face Triple H for the World Heavyweight Championship that night.[66] Michaels received the most votes and as a result, Edge and Benoit were forced to team up to face the World Tag Team Champions, La Résistance, in the same night. However, Edge deserted Benoit during the match and Benoit was forced to take on both members of La Résistance by himself. He and Edge still managed to regain the World Tag Team Championship. They lost the titles back to La Résistance on the November 1 episode of Raw.[65] At Survivor Series on November 14, Benoit sided with Randy Orton's team while Edge teamed with Triple H's team, and while Edge was able to pin Benoit after a Pedigree from Triple H, Orton's team won.[67]

The Benoit-Edge feud ended at New Year's Revolution on January 9, 2005 in an Elimination Chamber match for the World Heavyweight Championship, which both men lost.[68] The feud stopped abruptly, as Edge feuded with Shawn Michaels, and Benoit entered the Royal Rumble as the second entrant on January 30, lasting longer than any competitor before being eliminated by Ric Flair.[69] The two then continued to have matches in the following weeks until the two of them, Chris Jericho, Shelton Benjamin, Kane, and Christian were placed in the Money in the Bank ladder match at WrestleMania 21 on April 3. Edge won the match by knocking Benoit off of the ladder by smashing his arm with a chair.[69] The feud finally culminated in a Last Man Standing match at Backlash on May 1, which Edge won with a brick shot to the back of Benoit's head.[70]

United States Champion (2005–2007)

On June 9, Benoit was drafted to the SmackDown! brand after being the first man selected by SmackDown! in the 2005 Draft Lottery and participated in an ECW-style revolution against the SmackDown! heels.[71][72] Benoit appeared at ECW One Night Stand on June 12, defeating Eddie Guerrero.[73]

On July 24 at The Great American Bash, Benoit failed to win the WWE United States Championship from Orlando Jordan,[74] but won a rematch at SummerSlam on August 21 in 25 seconds.[74] Benoit then won three consecutive matches against Jordan in less than a minute.[75][76][77] Benoit later wrestled Booker T in friendly competitions,[74] until Booker T and his wife, Sharmell, cheated Benoit out of the United States title on the October 21 episode of SmackDown!.[78]

On November 13, Eddie Guerrero was found dead in his hotel room. The following night, Raw held a Guerrero tribute show hosted by both Raw and SmackDown! wrestlers. Benoit was devastated at Guerrero's death and was very emotional during a series of video testimonials, eventually breaking down on camera.[79] The same week on SmackDown! (taped on the same night as Raw), Benoit defeated Triple H in a tribute match to Guerrero. Following the contest, Benoit, Triple H, and Dean Malenko all assembled in the ring and pointed to the sky in salute of Guerrero.[80]

After controversy surrounding a United States Championship match against Booker T on the November 25 episode of SmackDown!, Theodore Long set up a "Best of Seven" series between the two. Booker T won three times in a row (at Survivor Series on November 27, the November 29 SmackDown! Special, and the December 9 episode of SmackDown!), due largely to Sharmell's interference, and Benoit faced elimination in the series.[81][82][83] Benoit won the fourth match to stay alive at Armageddon on December 18,[81] but after the match, Booker T suffered a legitimate groin injury, and Randy Orton was chosen as a stand-in. Benoit defeated Orton twice by disqualification on the December 30 and January 6, 2006, episodes of SmackDown!.[84][85] However, in the seventh and final match, Orton defeated Benoit with the help of Booker T, Sharmell, and Orlando Jordan, and Booker T captured the United States Championship.[86] Benoit feuded with Orton for a short time, before defeating Orton in a No Holds Barred match on the January 27 episode of SmackDown! via the Crippler Crossface.[87] Benoit was given one last chance at the United States Championship at No Way Out on February 19 and won it by making Booker T submit to the Crippler Crossface, ending the feud.[81]

The next week on SmackDown!, Benoit (kayfabe) broke John "Bradshaw" Layfield (JBL)'s hand (JBL actually needed surgery to remove a cyst).[88] A match was set up for the two at WrestleMania 22 on April 2 for Benoit's title, and for the next several weeks, they attacked each other. At WrestleMania, JBL won the match with an illegal cradle to win the title.[61] Benoit used his rematch clause two weeks later in a steel cage match on SmackDown!, but JBL again won with illegal tactics.[89] Benoit entered the King of the Ring tournament, only to be defeated by Finlay in the opening round on the May 5 episode of SmackDown!, after Finlay struck Benoit's neck with a chair and delivered a Celtic Cross.[90] At Judgment Day on May 21, Benoit gained some revenge by defeating Finlay with the Crippler Crossface in a grudge match.[91][92] On the following episode of SmackDown!, Mark Henry brutalized Benoit during their match, giving him (kayfabe) back and rib injuries and causing him to bleed from his mouth.[93] Benoit then took a sabbatical to heal nagging shoulder injuries.

On October 8, Benoit made his return at No Mercy, defeating William Regal in a surprise match.[94] Later that week, he won his fifth and final United States Championship from Mr. Kennedy.[95] Benoit then engaged in a feud with Chavo and Vickie Guerrero. He wanted answers from the Guerreros for their rash behaviour towards Rey Mysterio, but was avoided by the two and was eventually assaulted. This led to the two embarking on a feud with title matches at Survivor Series on November 26 and Armageddon on December 17; Benoit won both matches.[94] The feud culminated with one last title match as a No disqualification match on the January 19, 2007 episode of SmackDown!, which was also won by Benoit.[96] Later, Montel Vontavious Porter (MVP), who claimed that he was the best man to hold the United States title, challenged Benoit for the title at WrestleMania 23 on April 1, where Benoit retained.[62] Their rivalry continued with Benoit defeating MVP again at Backlash on April 29.[97] At Judgment Day on May 20, however, MVP gained the upper hand and defeated Benoit to win the title in a two out of three falls match, thus ending the feud.[98] Benoit would wrestle MVP one last time on the June 2 episode Saturday Night's Main Event, in a winning effort in a tag-team match where Benoit partnered with Batista and MVP partnered with then-World Heavyweight Champion Edge.[99]

ECW (2007)

On the June 11 episode of Raw, Benoit was drafted from SmackDown! to ECW as part of the 2007 WWE draft after losing to ECW World Champion Bobby Lashley.[100] In his debut on the ECW brand, Benoit teamed up with CM Punk in a tag team match against Elijah Burke and Marcus Cor Von, in which Benoit and Punk won.[101] On the June 19 episode of ECW, Benoit wrestled his final match, defeating Elijah Burke in a match to determine who would compete for the vacated ECW World Championship at Vengeance on June 24. Since Lashley was drafted to Raw, he had vacated the title.[102]

Benoit missed the weekend house shows, telling WWE officials that his wife and son were vomiting blood due to food poisoning. When he failed to show up for Vengeance, viewers were informed that he was unable to compete due to a "family emergency" and he was replaced in the title match by Johnny Nitro, who defeated Punk to become ECW World Champion. The crowd spent the majority of the match chanting for Benoit.[103] It would be revealed in the following days that Benoit had murdered his wife Nancy and son Daniel before committing suicide.

WWE executive Stephanie McMahon later indicated that Benoit would have defeated CM Punk for the ECW World Championship had he been present for Vengeance.[9] Professional wrestler and MMA fighter Bob Sapp, whom WWE had tried to sign up before a contract dispute with K-1 rendered it impossible, reported he would have been put into an oncoming angle with Benoit in case he would have been able to debut.[104]

Professional wrestling style

Benoit included a wide array of submission holds in his move-set and used a crossface, dubbed the Crippler Crossface, and a sharpshooter as finishers.[105][106] He also used a diving headbutt to finish off opponents.[107] The diving headbutt, which saw the deliverer leap off the top rope and land head first on the opponent, was partially blamed for the head trauma that caused Benoit to commit his crimes.[108][109] Another of Benoit's trademark moves was three rolling German suplexes.[110] This move would later be mimicked by multiple other wrestlers, including Brock Lesnar who uses it as Suplex City.[111]

Benoit was renowned for his high-impact technical style. Former WWE rival Kurt Angle said in a 2017 interview that "he has to got to be in the top three of all time."[112]

Professional wrestling games

Championships and accomplishments

- Cauliflower Alley Club

- Catch Wrestling Association

- Extreme Championship Wrestling

- New Japan Pro-Wrestling

- IWGP Junior Heavyweight Championship (1 time)[116]

- Super J-Cup (1994)[117]

- Top/Best of the Super Juniors (1993, 1995)[118]

- Super Grade Junior Heavyweight Tag League (1994) – with Shinjiro Otani[119]

- Pro Wrestling Illustrated

- Feud of the Year (2004) vs. Triple H[120]

- Match of the Year (2004) vs. Shawn Michaels and Triple H at WrestleMania XX[121]

- Wrestler of the Year (2004)[122]

- Ranked No. 1 of the top 500 singles wrestlers in the PWI 500 in 2004[123]

- Ranked No. 69 of the top 500 greatest wrestlers in the PWI Years in 2003[124]

- Stampede Wrestling

- Stampede British Commonwealth Mid-Heavyweight Championship (4 times)[24]

- Stampede Wrestling International Tag Team Championship (4 times) – with Ben Bassarab (1), Keith Hart (1), Lance Idol (1), and Biff Wellington (1)[125]

- Stampede Wrestling Hall of Fame (1995)[126]

- Universal Wrestling Association

- World Championship Wrestling

- World Wrestling Federation/Entertainment

- World Heavyweight Championship (1 time)[134]

- WWE Tag Team Championship (1 time, inaugural) – with Kurt Angle[135]

- WWE United States Championship (3 times)[136][137]

- WWF/WWE Intercontinental Championship (4 times)[138]

- WWF/World Tag Team Championship (3 times) – with Chris Jericho (1) and Edge (2)[139]

- Royal Rumble (2004)[140]

- WWE Tag Team Championship Tournament (2002) – with Kurt Angle[141]

- 12th Triple Crown Champion[133]

- Wrestling Observer Newsletter

- Best Brawler (2004)[142]

- Best Technical Wrestler (1994, 1995, 2000, 2003, 2004)[142]

- Feud of the Year (2004) vs. Shawn Michaels and Triple H[142]

- Match of the Year (2002) with Kurt Angle vs. Edge and Rey Mysterio at No Mercy[142]

- Most Outstanding Wrestler (2000, 2004)[142]

- Most Underrated (1998)[142]

- Readers' Favorite Wrestler (1997, 2000)[142]

- Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame (Class of 2003)[c][143]

Personal life

Benoit spoke both English and French fluently.[144] He married twice, and had two children (David and Megan) with his first wife, Martina.[145] By 1997, that marriage had broken down, and Benoit was living with Nancy Sullivan, the wife of the WCW booker and frequent opponent Kevin Sullivan. On February 25, 2000, Chris and Nancy's son Daniel was born; on November 23, 2000, Chris and Nancy married. It was Nancy's third marriage. In 2003, Nancy filed for divorce from Benoit, citing the marriage as "irrevocably broken" and alleging "cruel treatment". She claimed that he would break and throw furniture around.[146][147] She later dropped the suit as well as the restraining order she had filed.[146]

Benoit became good friends with fellow wrestler Eddie Guerrero following a match in Japan, when Benoit kicked Guerrero in the head and knocked him out cold.

Benoit was also close friends with Dean Malenko, as the trio travelled from promotion to promotion together putting on matches, eventually being dubbed the "Three Amigos" by commentators.[148] According to Chris Benoit, the Crippler Crossface was borrowed from Malenko and eventually caught on as Chris Benoit's finishing hold.[148][149]

Benoit's lost tooth, his top-right lateral incisor, was commonly misattributed to training or an accident early on in his wrestling career. It actually resulted from an accident involving his pet rottweiler: one day while playing with the dog, the animal's skull struck Benoit's chin, and his tooth "popped out".[150]

Death

On June 25, 2007, police entered Benoit's home in Fayetteville, Georgia,[151] when WWE, Benoit's employers, requested a "welfare check" after Benoit missed weekend events without notice, leading to concerns.[152] The officers discovered the bodies of Benoit, his wife Nancy, and their 7-year-old son Daniel at around 2:30 p.m. EDT.[153] Upon investigating, no additional suspects were sought by authorities.[154] It was determined that Benoit had committed the murders.[155] Over a three-day period, Benoit had killed his wife and son before committing suicide.[12][13] His wife was bound before the killing. Benoit's son was drugged with Xanax and likely unconscious before Benoit strangled him.[156] Benoit then committed suicide by hanging himself on his lat pulldown machine.[155][157]

WWE cancelled the scheduled three-hour-long live Raw show on June 25 and replaced the broadcast version with a three-hour tribute to Benoit's life and career, featuring his past matches, segments from the Hard Knocks: The Chris Benoit Story DVD, and comments from wrestlers and announcers.[158]

Toxicology reports released on July 17, 2007, revealed that at their time of death, Nancy had three different drugs in her system: Xanax, hydrocodone, and hydromorphone, all of which were found at the therapeutic rather than toxic levels. Daniel was found to have Xanax in his system, which led the chief medical examiner to believe that he was sedated before he was murdered. Benoit was found to have Xanax, hydrocodone, and an elevated level of testosterone, caused by a synthetic form of the hormone, in his system. The chief medical examiner attributed the testosterone level to Benoit possibly being treated for a deficiency caused by previous steroid abuse or testicular insufficiency. There was no indication that anything in Benoit's body contributed to his violent behaviour that led to the murder-suicide, concluding that there was no "roid-rage" involved.[159] Prior to the murder-suicide, Benoit had illegally been given medications not in compliance with WWE's Talent Wellness Program in February 2006, including nandrolone, an anabolic steroid, and anastrozole, a breast cancer medication which is used by bodybuilders for its powerful antiestrogenic effects. During the investigation into steroid abuse, it was revealed that other wrestlers had also been given steroids.[160][161]

After the double-murder suicide, neuroscientist and retired professional wrestler Christopher Nowinski contacted Michael Benoit, Chris's father, suggesting that years of trauma to his son's brain may have led to his actions. Tests were conducted on Benoit's brain by Julian Bailes, the head of neurosurgery at West Virginia University, and results showed that "Benoit's brain was so severely damaged it resembled the brain of an 85-year-old Alzheimer's patient."[162] He was reported to have had an advanced form of dementia, similar to the brains of four retired NFL players who had multiple concussions, sank into depression, and harmed themselves or others. Bailes and his colleagues concluded that repeated concussions can lead to dementia, which can contribute to severe behavioural problems.[162] Benoit's father suggests that brain damage may have been the leading cause.[163]

Once the details of Benoit's actions became apparent, WWE made the decision to remove nearly all mentions of Chris Benoit from their website,[164] future broadcasts, and all publications.[165]

See also

Notes

- ^ Benoit's reign with the championship is not recognized by WWE, who does not recognize any reign prior to December 1997.[128]

- ^ After Benoit left WCW for the WWF, WCW refused to acknowledge Benoit's victory as an official title reign, and Benoit's title reign was not listed in the title lineage at WCW.com.[34] However, the WWF recognized Benoit's title win, and Benoit's title reign is still listed in the title lineage at WWE.com.[35]

- ^ Benoit underwent a special recall election in 2008 due to the double murder-suicide of his wife and son. The recall was supported by a majority of 53.6% of voters, but was below the 60% threshold necessary to remove him.

References

- ^ a b Shields, Brian; Sullivan, Kevin (2009). WWE Encyclopedia. DK. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-7566-4190-0.

- ^ Randazzo V, Matthew (2008). Ring of Hell: The Story of Chris Benoit & the Fall of the Pro Wrestling Industry. Phoenix Books. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-59777-622-6.

- ^ McCoy, Heath (2007). Pain and Passion: The History of Stampede Wrestling. ECW Press. pp. 214–215. ISBN 978-1-55022-787-1.

- ^ Hart, Bruce (2011). Straight From the Hart. ECW Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-55022-939-4.

- ^ "Erased! The Tragic Story of Chris Benoit". Wrestling Examiner. February 9, 2017. Archived from the original on September 22, 2020. Retrieved May 21, 2017.

Benoit began training at the legendary New Japan Dojo, and began wrestling for NJPW

- ^ a b "Chris Benoit Results Archive". Slam! Sports. Canadian Online Explorer. Archived from the original on June 24, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2019.

- ^ "Inside WWE > Title History > WCW World Championship". WWE. Archived from the original on May 22, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- ^ "Inside WWE > Title History > World Heavyweight Championship". WWE. Archived from the original on March 12, 2012. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b "U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Government Oversight and Reform – Interview of: Stephanie McMahon Levesque (p. 81)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 3, 2009. Retrieved December 3, 2009.

Ironically, Mr. Benoit was supposed to become ECW champion that night, and he didn't show up at the [Vengeance: Night of Champions] pay‐per‐view because he was dead.

- ^ "TV Shows > Royal Rumble > History > 2004 > Rumble Match". WWE. Archived from the original on June 11, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- ^ "Full WrestleMania XX Results". WWE. Archived from the original on November 23, 2019. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- ^ a b "Wrestler Chris Benoit Double murder–suicide: Was It 'Roid Rage'? – Health News | Current Health News". FOXNews.com. June 27, 2007. Archived from the original on June 5, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b "Benoit's Dad, Doctors: Multiple Concussions Could Be Connected to murder–suicide – ABC News". Abcnews.go.com. September 5, 2007. Archived from the original on June 12, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b Chris Benoit murder-suicide full documentary, no commercials, archived from the original on July 21, 2022, retrieved May 1, 2021

- ^ Williams, Ian (May 8, 2020). "The Horrific Crime That Changed WWE Forever". Vice. Archived from the original on November 7, 2020. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ "Your e-mails: Reaction to Chris Benoit deaths". CNN. June 26, 2007. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ "Benoit's Public Image Hid Monster". Calgary Herald. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved February 1, 2009.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Stampede Wrestling Hall Of Fame". Wrestling-Titles.com. Archived from the original on September 26, 2009. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ^ "Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame, 2003". Profightdb.com. Archived from the original on February 13, 2022. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ^ Mentioned by his father in an interview with Larry King on CNN.

- ^ a b c d Lunney, Doug (January 15, 2000). "Benoit inspired by the Dynamite Kid, Crippler adopts idol's high-risk style". Archived from the original on June 29, 2012. Retrieved May 10, 2007.

- ^ a b Lewis, Michael (November 14, 2007). "The Last Days of Chris Benoit". Maxim. Archived from the original on September 25, 2016. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- ^ a b Bret "Hit Man" Hart: The Best There Is, the Best There Was, the Best There Ever Will Be (DVD). WWE Home Video. 2005. Event occurs at 59 & 118 minutes.

Growing up as a fan, and once I began wrestling, I always looked up to him; I always emulated him [...] Bret Hart, the man that I spent so many years looking up to, idolizing; he was somewhat of a role model to me.

- ^ a b "Stampede Wrestling British Commonwealth Mid-Heavyweight Title". wrestling-titles.com. Archived from the original on December 1, 2010. Retrieved February 8, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Royal Duncan & Gary Will (2006). Wrestling Title Histories (4th ed.). Archeus Communications. ISBN 0-9698161-5-4.

- ^ Scott E. Williams (December 13, 2013). Hardcore History: The Extremely Unauthorized Story of ECW. Skyhorse Publishing Company, Incorporated. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-1-61321-582-1.

- ^ Thom Loverro (May 22, 2007). The Rise & Fall of ECW: Extreme Championship Wrestling. Simon and Schuster. pp. 67–78. ISBN 978-1-4165-6156-9.

- ^ a b Randazzo V, Matthew (2008). Ring of Hell: The Story of Chris Benoit & The Fall of the Pro Wrestling Industry. Phoenix Books. pp. 162–163. ISBN 978-1-59777-622-6.

- ^ Cawthon, Graham (January 10, 2024). "Yearly Results: 1995". TheHistoryOfWWE.com. Archived from the original on December 4, 2023.

- ^ Chris Benoit (1967–2007) profile Archived December 2, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, MetaFilter.com; accessed June 30, 2015.

- ^ a b Cole, Glenn (April 17, 1999). "Ring of intrigue in WWF shows". SLAM! Sports. Canadian Online Explorer. Archived from the original on June 9, 2015. Retrieved May 12, 2009.

- ^ "Souled Out 2000". Pro Wrestling History. Archived from the original on June 23, 2008. Retrieved October 3, 2007.

- ^ "Wrestling Information Archive - Wrestling Timeline: (1999 - Present)". August 4, 2001. Archived from the original on August 4, 2001.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b "World Heavyweight Champion and WCW/NWA Title History". WCW.com. Archived from the original on August 17, 2000. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b "WCW World Championship". WWE.com. Archived from the original on July 15, 2017. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- ^ "Chris Benoit". WWE.com. Archived from the original on August 2, 2002. Retrieved October 23, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Intercontinental Championship". World Wrestling Entertainment. Archived from the original on February 1, 2023. Retrieved February 5, 2023.

- ^ "WrestleMania X-Seven report". The Other Arena. Archived from the original on April 4, 2008. Retrieved February 9, 2008.

- ^ McAvennie, Michael (2003). "WWE The Yearbook: 2003 Edition". Pocket Books. p. 102.

- ^ McAvennie, Michael (2003). "WWE The Yearbook: 2003 Edition". Pocket Books. p. 148.

- ^ McAvennie, Michael (2003). "WWE The Yearbook: 2003 Edition". Pocket Books. p. 200.

- ^ McAvennie, Michael (2003). "WWE The Yearbook: 2003 Edition". Pocket Books. p. 197.

- ^ a b "Wrestling's Historical Cards". 2007 Wrestling Almanac & Book of Facts. Kappa Publishing. 2007. p. 111.

- ^ McAvennie, Michael (2003). "WWE The Yearbook: 2003 Edition". Pocket Books.

- ^ McAvennie, Michael (2003). "WWE The Yearbook: 2003 Edition". Pocket Books. pp. 279–280.

- ^ McAvennie, Michael (2003). "WWE The Yearbook: 2003 Edition". Pocket Books. pp. 291–296.

- ^ "Wrestling's historical cards". Pro Wrestling Illustrated presents: 2007 Wrestling almanac & book of facts. Kappa Publishing. 2007. p. 112.

- ^ Hurley, Oliver (February 21, 2003). ""Every Man for himself" (Royal Rumble 2003)". Power Slam Magazine, issue 104. SW Publishing. pp. 16–19.

- ^ "SmackDown—February 27, 2003 Results". Archived from the original on December 5, 2009. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ "Wrestling's Historical Cards". 2007 Wrestling Almanac & Book of Facts. Kappa Publishing. 2007. pp. 112–113.

- ^ "SmackDown Results". April 17, 2003. Archived from the original on August 3, 2010. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ "SmackDown Results". April 24, 2003. Archived from the original on April 22, 2008. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ a b "Wrestling's Historical Cards". 2007 Wrestling Almanac & Book of Facts. Kappa Publishing. 2007. p. 113.

- ^ "Wrestling's Historical Cards". 2007 Wrestling Almanac & Book of Facts. Kappa Publishing. 2007. pp. 113–114.

- ^ a b c d e "Wrestling's Historical Cards". 2007 Wrestling Almanac & Book of Facts. Kappa Publishing. 2007. p. 114.

- ^ "SmackDown Results". December 4, 2003. Archived from the original on January 27, 2010. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ "SmackDown Results". January 1, 2004. Archived from the original on January 28, 2010. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ "RAW Results". January 24, 2004. Archived from the original on December 30, 2009. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ "RAW Results". February 16, 2004. Archived from the original on January 29, 2010. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ a b PWI Staff (2007). "Wrestling's historical cards". Pro Wrestling Illustrated presents: 2007 Wrestling almanac & book of facts. Kappa Publishing. p. 115.

- ^ a b Hurley, Oliver (April 20, 2006). "Power Slam Magazine, issue 142". "WrestleMania In Person" (WrestleMania 22). SW Publishing. pp. 16–19.

- ^ a b McElvaney, Kevin (June 2007). "Pro Wrestling Illustrated". WrestleMania 23. Kappa Publishing. pp. 74–101.

- ^ "RAW Results". April 19, 2004. Archived from the original on January 19, 2010. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ "World Heavyweight Champion Chris Benoit defeats Triple H to retain". World Wrestling Entertainment. Archived from the original on October 12, 2011. Retrieved July 29, 2007.

- ^ a b "Wrestling's Historical Cards". 2007 Wrestling Almanac & Book of Facts. Kappa Publishing. 2007. p. 116.

- ^ "RAW Results". October 18, 2004. Archived from the original on July 15, 2010. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ "Wrestling's Historical Cards". 2007 Wrestling Almanac & Book of Facts. Kappa Publishing. 2007. pp. 116–117.

- ^ Evans, Anthony (January 21, 2005). "Power Slam Magazine, issue 127". Tripper strikes back (New Years Revolution 2005). SW Publishing. pp. 30–31.

- ^ a b "Wrestling's Historical Cards". 2007 Wrestling Almanac & Book of Facts. Kappa Publishing. 2007. p. 117.

- ^ Power Slam Staff (May 21, 2005). "WrestleMania rerun (Backlash 2005)". Power Slam Magazine, issue 131. SW Publishing. pp. 32–33.

- ^ "SmackDown Results". June 9, 2005. Archived from the original on July 15, 2010. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ "Power Slam". What's going down... SW Publishing LTD. p. 5. 132.

- ^ "ECW One Night Stand 2005 Results". Archived from the original on April 28, 2007. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ a b c "Wrestling's Historical Card". 2007 Wrestling Almanac & Book of Facts. Kappa Publishing. 2007. p. 118.

- ^ "SmackDown Results". September 1, 2005. Archived from the original on December 1, 2009. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ "SmackDown Results". September 8, 2005. Archived from the original on February 13, 2008. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ "SmackDown Results". September 23, 2005. Archived from the original on July 15, 2010. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ "SmackDown Results". October 21, 2005. Archived from the original on July 16, 2010. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ "RAW — 14 November 2005 Results". Archived from the original on March 18, 2008. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ "SmackDown Results". November 18, 2005. Archived from the original on December 1, 2009. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ a b c "Wrestling's Historical Cards". 2007 Wrestling Almanac & Book of Facts. Kappa Publishing. 2007. p. 119.

- ^ "SmackDown Special Results". November 29, 2005. Archived from the original on April 21, 2008. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ "SmackDown Results". December 9, 2005. Archived from the original on July 15, 2010. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ "SmackDown Results". December 30, 2005. Archived from the original on July 15, 2010. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ "SmackDown Results". January 6, 2006. Archived from the original on January 1, 2010. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ "Pro Wrestling Illustrated, May 2006". Arena Reports. Kappa Publishing. May 2006. p. 130.

- ^ "Pro Wrestling Illustrated". Arena Reports. Kappa Publishing. May 2006. p. 132.

- ^ "SmackDown Results". February 24, 2006. Archived from the original on July 24, 2013. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ "SmackDown Results". April 14, 2006. Archived from the original on January 1, 2010. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ "SmackDown Results". May 5, 2006. Archived from the original on January 1, 2010. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ "Wrestling's Historical Cards". 2007 Wrestling Almanac & Book of Facts. Kappa Publishing. 2007. p. 121.

- ^ Brett Hoffman (May 21, 2006). "A Good Old-Fashioned Fight". WWE. Archived from the original on January 3, 2008. Retrieved January 5, 2008.

- ^ "SmackDown Results". May 26, 2006. Archived from the original on January 1, 2010. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ a b "Wrestling's Historical Cards". 2007 Wrestling Almanac & Book of Facts. Kappa Publishing. 2007. p. 122.

- ^ "SmackDown-October 13, 2006 Results". Archived from the original on January 1, 2010. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ "Pro Wrestling Illustrated". Arena Reports. Kappa Publishing. May 2007. p. 130.

- ^ "Backlash 2007 Results". Archived from the original on November 26, 2007. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ "Judgment Day 2007 Results". Archived from the original on April 13, 2016. Retrieved June 29, 2007.

- ^ "Edge & MVP vs Chris Benoit & Batista, Saturday Night's Main Event XXXIV". Dailymotion. January 13, 2015. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Raw Results". June 11, 2007. Archived from the original on December 15, 2007. Retrieved June 29, 2007.

- ^ "ECW results - June 12, 2007". Online World of Wrestling. Retrieved April 3, 2008.

- ^ "ECW Results". June 19, 2007. Archived from the original on July 23, 2010. Retrieved June 29, 2007.

- ^ Powell, John; Powell, Justin (June 25, 2007). "Vengeance banal and badly booked". SLAM! Sports. Canadian Online Explorer. Archived from the original on May 19, 2015. Retrieved November 6, 2007.

- ^ Jonathan Snowden (2010). Total Mma: Inside Ultimate Fighting. ECW Press. ISBN 978-15-549033-7-5.

- ^ Keller, Wade (October 25, 2009). "Torch Flashbacks Keller's WWE Taboo Tuesday PPV Report 5 YRS. Ago (10–19–04): Triple H vs. Shawn Michaels, Randy Orton vs. Ric Flair, Shelton Benjamin IC Title victory vs. Chris Jericho". PW Torch. Archived from the original on October 27, 2009. Retrieved November 11, 2009.

- ^ Martin, Adam (April 18, 2004). "Full WWE Backlash (Raw) PPV Results – 4/18/04 from Edmonton, Alberta, CA". WrestleView. Archived from the original on February 7, 2008. Retrieved February 15, 2008.

- ^ "Chris Benoit". accelerator3359.com. Archived from the original on June 8, 2018. Retrieved May 28, 2018.

- ^ "Two Big Things Played A Part In Chris Benoit's Death And We Need To Talk About It". Unilad.co.uk. Archived from the original on April 15, 2019. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ Bixenspan, David (June 26, 2017). "10 Years After The Chris Benoit Killings, Pro Wrestling Still Can't Fix Itself". Deadspin. Archived from the original on April 15, 2019. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ Sokol, Chris (July 11, 2004). "Canadians have Edge at Vengeance". Slam! Sports. Canadian Online Explorer. Archived from the original on November 11, 2016. Retrieved November 11, 2009.

- ^ "The 10 coolest moves in WWE right now". WWE. September 26, 2014. Archived from the original on September 29, 2014. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ Edwards, Jonathan (April 17, 2017). "Kurt Angle Says Chris Benoit Is Top 3 Wrestler All Time". ScreenGeek. Archived from the original on April 15, 2019. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ "Past Honorees". Archived from the original on April 11, 2009. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- ^ "Catch Wrestling Association Title Histories". titlehistories.com. Archived from the original on July 20, 2008. Retrieved July 11, 2008.

- ^ "ECW World Tag Team Title history". Wrestling-titles.com. Archived from the original on October 4, 2012. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ "IWGP Junior Heavyweight Title history". Wrestling-titles.com. Archived from the original on December 16, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- ^ Royal Duncan & Gary Will (2000). "Japan; New Japan Super Junior Heavyweight (Super J) Cup Tournament Champions". Wrestling Title Histories. Archeus Communications. p. 375. ISBN 0-9698161-5-4.

- ^ Royal Duncan & Gary Will (2000). "Japan; Top of the Super Junior Heavyweight Champions". Wrestling Title Histories. Archeus Communications. p. 375. ISBN 0-9698161-5-4.

- ^ "New Japan Misc. Junior Tournaments". Prowrestlinghistory.com. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ^ "Pro Wrestling Illustrated Award Winners – Feud of the Year". Wrestling Information Archive. Archived from the original on June 16, 2008. Retrieved May 4, 2008.

- ^ "Pro Wrestling Illustrated Award Winners – Match of the Year". Wrestling Information Archive. Archived from the original on June 16, 2008. Retrieved May 4, 2008.

- ^ "Pro Wrestling Illustrated Award Winners – Wrestler of the Year". Wrestling Information Archive. Archived from the original on June 19, 2008. Retrieved May 4, 2008.

- ^ "Pro Wrestling Illustrated Top 500 – 2004". Wrestling Information Archive. Archived from the original on February 9, 2009. Retrieved May 4, 2008.

- ^ "PWI 500 of the PWI Years". Archived from the original on April 1, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- ^ "Stampede International Tag Team Title history". Wrestling-titles.com. Archived from the original on May 5, 2008. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ "Stampede Wrestling Hall of Fame Inductees history". Wrestling-titles.com. Archived from the original on August 16, 2001. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ "WWF World Light Heavyweight Title history". Wrestling-titles.com. Archived from the original on March 11, 2011. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ "WWE light Heavyweight Championship official history". WWE. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ "WCW World Heavyweight Title history". Wrestling-titles.com. Archived from the original on February 13, 2012. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ "WCW World Tag Team Title history". Wrestling-titles.com. Archived from the original on February 26, 2008. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ "NWA/WCW World Television Title history". Wrestling-titles.com. Archived from the original on January 19, 2012. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ "NWA/WCW United States Heavyweight Title history". Wrestling-titles.com. Archived from the original on August 3, 2014. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ a b "In Memory of Chris Benoit & more". Sportskeeda. June 25, 2012. Archived from the original on January 16, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- ^ "World Heavyweight Title (WWE Smackdown) history". Wrestling-titles.com. Archived from the original on August 20, 2010. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ "WWE Tag Team Title (Smackdown) history". Wrestling-titles.com. Archived from the original on January 12, 2010. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ "WWWF/WWE United States Heavyweight Title history". Wrestling-titles.com. Archived from the original on March 7, 2011. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ "WWE United States Championship". Archived from the original on December 12, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- ^ "WWF/WWE Intercontinental Heavyweight Title history". Wrestling-titles.com. Archived from the original on July 5, 2014. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ "WWWF/WWF/WWE World Tag Team Title history". Wrestling-titles.com. Archived from the original on April 17, 2010. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ "Royal Rumble 2004 Full Event Results". WWE. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2018.

- ^ "WWE Tag Team Title Tournaments". Pro Wrestling History. Archived from the original on June 30, 2020. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Meltzer, Dave (January 26, 2015). "Jan. 26, 2015 Wrestling Observer Newsletter: 2014 awards issue w/ results & Dave's commentary, Conor McGregor, and much more". Wrestling Observer Newsletter. Campbell, California. pp. 4–29. ISSN 1083-9593. Archived from the original on February 15, 2015. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ "Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame". PWI-Online.com. Archived from the original on May 5, 2019. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ "Benoit tragedy, one year later". SLAM! sports. Archived from the original on July 28, 2012. Retrieved July 9, 2008.

- ^ "Details of Benoit family deaths revealed". TSN. Associated Press. June 26, 2007. Archived from the original on February 13, 2008. Retrieved June 28, 2007.

- ^ a b "WWE star killed family, self". SportsIllustrated.cnn.com. Associated Press. June 26, 2007. Archived from the original on May 24, 2011. Retrieved June 26, 2007.

- ^ "Released divorce papers and restraining order" (PDF). TMZ.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 27, 2007. Retrieved June 27, 2007.

- ^ a b Benoit interview, "Chris Benoit: Hard Knocks" DVD, WWE Home Video.

- ^ Malenko comments on Benoit, WWE Raw, June 25, 2007.

- ^ Interview with his father, "Hard Knocks" DVD

- ^ "WWE wrestler Chris Benoit and family found dead". June 25, 2007. Archived from the original on July 5, 2007. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ^ Ahmed, Saeed and Kathy Jefcoats (June 25, 2007). "Pro wrestler, family found dead in Fayetteville home". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on June 27, 2007. Retrieved November 27, 2008.

- ^ "Canadian wrestler Chris Benoit, family found dead". CBC.ca. June 25, 2007. Archived from the original on June 11, 2010. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ^ "Wrestling Champ Chris Benoit Found Dead with Family". ABC News. June 25, 2007. Archived from the original on April 15, 2008. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ^ a b "Sheriff: Wrestler Chris Benoit murder–suicide Case Closed – Local News | News Articles | National News". FOXNews.com. February 12, 2008. Archived from the original on January 14, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- ^ Red, Christian (July 18, 2007). "Benoit strangled unconscious son – doc". New York: Nydailynews.com. Archived from the original on September 10, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- ^ David Lohr (June 25, 2007). "Authorities Confirm Chris Benoit Murdered Wife and Son". CrimeLibrary.com. Archived from the original on April 17, 2008. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ "WWE postpones show at American Bank Center". Caller-Times. June 25, 2007. Archived from the original on June 28, 2007. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ^ "Wrestler Chris Benoit Used Steroid Testosterone; Son Sedated Before Murders". FOXnews. July 17, 2007. Archived from the original on September 4, 2009. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ "Fourteen wrestlers tied to pipeline". Sports Illustrated. August 30, 2007. Archived from the original on February 27, 2013. Retrieved September 1, 2007.

- ^ Farhi, Paul (September 1, 2007). "Pro Wrestling Suspends 10 Linked to Steroid Ring". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved September 1, 2007.

- ^ a b "Benoit's Brain Showed Severe Damage From Multiple Concussions, Doctor and Dad Say". abcnews.go.com. Archived from the original on September 8, 2007. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- ^ "Brain Study: Concussions Caused Benoit's Rage". WSB Atlanta. Archived from the original on November 16, 2007. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- ^ "Superstars". WWE. Archived from the original on January 5, 2007. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ^ "Sheriff: Wrestler Chris Benoit murder–suicide Case Closed". FOXNews.com. February 12, 2008. Archived from the original on March 22, 2008. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

Sources

- Royal Duncan & Gary Will (2006). Wrestling Title Histories (4th ed.). Archeus Communications. ISBN 978-0-9698161-5-7.

- Kevin Dunn (Director) (2004). Hard Knocks: The Chris Benoit Story (DVD). WWE Home Video.

- SLAM! Wrestling — Chris Benoit[usurped]

- Metro — 60 Seconds: Chris Benoit by Andrew Williams

- Wrestling Digest: Technically Speaking, wrestler and sports entertainer Chris Benoit

External links

- Chris Benoit at IMDb

- World Championship Wrestling profile at the Wayback Machine (archived May 8, 1999)

- World Wrestling Entertainment profile at the Wayback Machine (archived June 17, 2005)

- Chris Benoit's profile at Cagematch.net , Wrestlingdata.com , Internet Wrestling Database

- 1967 births

- 2007 suicides

- 21st-century Canadian criminals

- 20th-century male professional wrestlers

- 20th-century Canadian professional wrestlers

- 20th-century Canadian sportsmen

- 21st-century male professional wrestlers

- 21st-century Canadian professional wrestlers

- Best of the Super Juniors winners

- Canadian emigrants to the United States

- Canadian expatriate professional wrestlers in the United States

- Canadian football offensive linemen

- Canadian male criminals

- Canadian male professional wrestlers

- Canadian murderers of children

- Canadian people of French descent

- Criminals from Georgia (U.S. state)

- Criminals from Montreal

- CWA World Tag Team Champions

- ECW World Tag Team Champions

- Expatriate professional wrestlers in Japan

- Franco-Albertan people

- IWGP Junior Heavyweight champions

- Male murderers

- Masked wrestlers

- Murder–suicides in Georgia (U.S. state)

- NWA/WCW World Television Champions

- NWA/WCW/WWE United States Heavyweight Champions

- Professional wrestlers from Alberta

- Professional wrestlers with chronic traumatic encephalopathy

- Sportspeople from Edmonton

- Suicides by hanging in Georgia (U.S. state)

- The Four Horsemen (professional wrestling) members

- Professional wrestlers from Montreal

- Stampede Wrestling British Commonwealth Mid-Heavyweight Champions

- Stampede Wrestling International Tag Team Champions

- WCW World Tag Team Champions

- Royal Rumble match winners

- World Tag Team Champions (WWE, 1971–2010)

- WCW World Heavyweight Champions

- WWF/WWE Intercontinental Champions

- WWF Light Heavyweight Champions

- World Tag Team Champions (WWE)