Glenmore Reservoir

| Glenmore Reservoir | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Calgary, Alberta |

| Coordinates | 50°59′21″N 114°06′49″W / 50.98917°N 114.11361°W |

| Lake type | reservoir |

| Primary inflows | Elbow River |

| Primary outflows | Elbow River |

| Catchment area | 1,210 km2 (470 sq mi)[1] |

| Basin countries | Canada |

| Max. length | 4.1 km (2.5 mi) |

| Max. width | 0.9 km (0.56 mi) |

| Surface area | 3.84 km2 (1.48 sq mi)[1] |

| Average depth | 6.1 m (20 ft)[1] |

| Max. depth | 21.1 m (69 ft) |

| Surface elevation | 1,080 m (3,540 ft) |

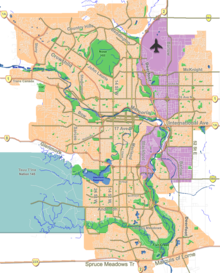

The Glenmore Reservoir is a large reservoir on the Elbow River in the southwest quadrant of Calgary, Alberta. It is controlled by the Glenmore Dam, a concrete gravity dam on the Elbow River. The Glenmore Reservoir is a primary source of drinking water to the city of Calgary. Built in 1932, with a cost of $3.8 million, the dam controls the downstream flow of the Elbow River, thus allowing the city to develop property near the river's banks with less risk of flooding.[2]

The reservoir’s perimeter features a scenic, uninterrupted 16km multi-use pathway/pedestrian and cycling trail along the water’s edge, connecting popular city destinations such as the Heritage Marina beach, Heritage Park Historical Village, South Glenmore Park, Glenmore Sailing Club, Weaselhead Flats Natural Environment Park, North Glenmore Park, Calgary Canoe Club, Calgary Rowing Club, and the Earl Grey Golf Club Archived 2024-04-18 at the Wayback Machine.

The reservoir has a water mirror of 3.84 km2 (1.48 sq mi) and a drainage basin of 1,210 km2 (470 sq mi).[1] From 2017 to 2020, the City of Calgary rehabilitated and upgraded the Glenmore Dam at a cost of $81 million.[3][4]

The reservoir is bordered to the west by the Tsuut’ina Nation reserve, to the north by the communities of Lakeview and North Glenmore, to the east by the neighbourhood Eagle Ridge (which sits on the peninsula alongside Heritage Park), and to the south by the communities of Oakridge, Palliser, and Pump Hill.

History

[edit]

The Glenmore Reservoir is located on land originally settled by Calgary pioneer Sam Livingston, who gave the area the name Gleann Mór (Gaelic for "Big Valley").

The City of Calgary began contemplating the need for a new source of drinking water in the early 1900s. City Alderman John Goodwin Watson proposed a gravity water supply fed from the Elbow River in April 1907.[5] The issue of water scarcity and runoff continued to compound in the 1920s with the Calgary Herald reporting the muddy conditions of the Elbow and Bow River in April 1926. The city retained Canadian architecture firm Gore, Naismith and Storrie to study the inadequate and frequently contaminated water supply in July 1929, with the firm recommending 12 remediation options, including the Glenmore Dam and Reservoir.[6][7]

The City of Calgary would eventually receive approval for a dam and reservoir from the Government of Canada under the Irrigation Act in the late 1920s. The final step was approval from the electorate, which came in the form of a plebiscite during the 1929 Calgary municipal election. The electors of Calgary approved a bylaw to borrow $2.77-million for the project and other waterworks improvements.[8]

With the necessary federal approval and financing in place, the city began purchasing land in the area necessary to complete the project. This including 539.5 acres from the Tsuu T'ina Nation (formerly the Sarcee Indian Reservation). The final price paid was $50 per acre, totaling $29,675. The purchase was negotiated by lawyer Leonard Brockington on behalf of the city. Brockington was known by the Tsuu T'ina Nation, and had previously been given the name "Chief Yellow Coming Over the Hill", and as a condition of the sale, Brockington was bestowed the name "Chief Weasel Head" after the traditional name of the area to ensure the name would continue to live on.[9] The city had independently valued the Tsuu T'ina land at $32,642.50, a difference of $2,596.50 over the final price. Other land owners in the area were paid between $111 and $400 per acre for the project.[10]

Mayor Andrew Davison turned the first sod in a ceremony on July 26, 1930, to inaugurate the largest infrastructure project undertaken by the city to date. First concrete was poured on October 13, 1930, and in the fall of 1931 McDiarmid began construction of the water purification plant.[7]

The expensive land purchases and growing cost of the project led to a judicial inquiry headed by Supreme Court of Alberta Justice Albert Ewing in 1932. The inquiry investigated all aspects of the project's financing including land acquisitions, awarding of contracts, labour practices and management. The final report by Justice Ewing found no evidence of wrongdoing.[7]

The dam was completed and became operational on January 19, 1933, which happened without an official ceremony. A public open house was held one week afterwards, which was attended by thousands of Calgarians.[7]

When the area flooded (by the summer of 1933), part of the Livingston house was preserved and now stands in Heritage Park, which borders the reservoir.

The design estimated capacity for serving a population of 200,000, but by 1949 the system was reported as "under near-constant strain" with a population of 105,000 Calgarians. The city completed a $1.5-million filtration extension in 1957 which doubled the water capacity.[7] Additional capacity was added again in 1965 with eight filter beds and a high lift pumping station. Administration and a research laboratory were completed in 1979.[7] The city subsequently constructed the Bearspaw Treatment plant in 1972 on the Bow River to supplement the city's water supply.[7]

2005 flood

[edit]Although the dam usually provides effective flood protection, a major flood in June 2005 caused the reservoir to exceed its capacity. The excess spilled over the dam and into the river. The flow downstream increased from its normal average of 20-30 cubic metres per second up to 350 cubic metres per second. As a result, some roads were closed and 2,000 Calgarians who lived downstream were evacuated.[11] The Glenmore water treatment plant had difficulty treating the heavily silted water, which caused the municipal government to issue water restrictions. Environment Canada noted the 2005 Alberta floods were a 200-year flood occurrence.[12]

2013 flood

[edit]In June 2013, heavy rainfall west of the city caused the reservoir to exceed its capacity. As it did in 2005, excess water spilled over the dam and into the Elbow River, with downstream flows up to 544 cubic metres per second. 75,000 people[13] from 26 neighbourhoods in the vicinity of the Bow and Elbow rivers were placed under a mandatory evacuation order as the rivers spilled over their banks and flooded neighbourhoods. City officials urged Calgarians, particularly the 350,000 people who worked downtown, to stay home and limit non-essential travel. Unlike the 2005 flood, the Glenmore water treatment facility had no difficulty treating water. City officials did, however, implement municipal outdoor watering restrictions to ensure water quality remained high throughout the incident. Government officials called the flooding the worst in Alberta's history. After the flood, studies commissioned by the city and province investigated the construction of a $457 million tunnel to divert water from future flooding.[14]

2018-2020 Upgrades

[edit]In 2018, a three-year project began to upgrade the ageing Glenmore Dam, increasing its capacity and improving its flood resistance. The dam itself was rehabilitated; 2.5m steel gates were added to the top of the dam which increased capacity by roughly 10 billion litres; and the bridge deck atop the dam was replaced in order to create more space for pathway users. This $81 million project also involved drawing down the reservoir during 2018 to the point that only hand launched boats were able to use the reservoir for sailing, and Heritage Park's S.S. Moyie paddlewheeler was forced to remain in drydock.[15] [16][17] [18]

Features

[edit]The Glenmore Dam is a gravity dam which uses the downward force (weight) of the structure to resist the horizontal pressure of the water within the dam. These massive dams resist the thrust of water entirely by their own weight.

The Glenmore Water Treatment Plant, constructed in three phases in 1933, 1957 and 1965, is a conventional treatment plant that gets its water from the Elbow River. The Glenmore plant supplies drinking water to south Calgary.

Flood control

[edit]The reservoir is maintained at a level that, depending on the flow rate of the Elbow River, minimizes the risk of flooding around the reservoir and downstream of the dam to the greatest degree possible. During periods when the rate flow of the Elbow River reaches dangerous levels, water may be released from the dam to prevent overflow.[19][better source needed]

Recreation

[edit]The City of Calgary offers sailing lessons and boat rentals on the reservoir. The reservoir is home of the Glenmore Sailing Club Archived 2018-05-27 at the Wayback Machine, the Calgary Rowing Club and the Calgary Canoe Club for both social and organized sporting events in Calgary. From May 1 to October 31 the reservoir is open for fishing, sailing, rowing and canoeing. Swimming in the reservoir is not permitted.

There are popular pathways and bikeways looping around the perimeter of Glenmore Reservoir that are open all year.

Bylaws

[edit]The Glenmore Reservoir and Dam were constructed to provide Calgarians a safe and sufficient supply of drinking water with bylaws put in place to maintain the quality of the water. Under the Water Utility Bylaw, no person shall:

- enter or remain in or upon the water or the ice of the Glenmore Reservoir;

- place any object or thing in the water or upon the ice of the Glenmore Reservoir or any stream flowing into the Glenmore Reservoir;

- do anything or place or throw anything which may pollute or contaminate the water of the Glenmore Reservoir;

- allow any drain to be connected to any structure or device which drains into the Glenmore Reservoir.[20]

Dogs on the reservoir

[edit]Under Calgary's Responsible Pet Ownership Bylaw, the owner of any animal must ensure that their animal does not enter or remain in the water or upon the ice of the Glenmore Reservoir at any time.

Related bylaws

[edit]Glenmore Reservoir regulations are found in section 23 of the Water Utility Bylaw Archived 2015-05-08 at the Wayback Machine and in section 16 of the Responsible Pet Ownership Bylaw Archived 2018-01-19 at the Wayback Machine.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d University of Alberta. "Atlas of Alberta Lakes: Glenmore Reservoir". Archived from the original on 2020-10-19. Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- ^ Sanders, Harry Max (2000). Watermarks: one hundred years of Calgary Waterworks. Calgary: City of Calgary. OCLC 65604061.

- ^ "Glenmore Dam to get $82M in upgrades from City of Calgary". CBC News. September 25, 2014. Archived from the original on August 16, 2018. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

- ^ Markusoff, Jason (September 16, 2014). "City to request $10M for Glenmore Dam upgrades". Calgary Herald. Archived from the original on January 31, 2015. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

- ^ Gilpin, John (January 3, 2007). "New book traces the history of Calgary on the Elbow". Calgary Herald. Archived from the original on 10 October 2023. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ "Glenmore Water Treatment Plant". Alberta Register of Historic Place. Government of Alberta. Archived from the original on May 14, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bobrovitz, Jennifer (1999). "Glenmore Dam, Calgary, Alberta, Canada (Folded)". Calgary Public Library. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ City of Calgary (1942). Calgary Municipal Manual. Calgary: City of Calgary. p. 90. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ Salus, Jesse (May 13, 2019). "Finding Weaselhead". The History of a Road. Archived from the original on 7 November 2020. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ Salus, Jesse (July 7, 2013). "The Glenmore Land Claims". The History of a Road. Archived from the original on 13 November 2020. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ "Floods force Calgary to declare state of emergency". The Globe and Mail. Calgary. June 19, 2005. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ "Top ten weather stories for 2005: story one: 1. Alberta's Flood of Floods". ec.gc.ca. Environment and Climate Change Canada. 27 November 2009. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ MacIntosh, Cameron (June 23, 2013). "Cameron MacIntosh reflects on the Calgary flood: Reporter's notebook: June is always a dangerous time in the Prairies". CBC News. Archived from the original on October 10, 2023. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

- ^ Calgary's Flood Resilient Future (PDF) (Report). Expert Management Panel on River Flood Mitigation. June 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 26, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- ^ "Glenmore Dam infrastructure improvements". Archived from the original on 2023-11-25. Retrieved 2023-10-09.

- ^ "Pathway atop Glenmore Dam reopens as $81M upgrade finishes". CBC. 2020-09-04. Archived from the original on 2023-11-25.

- ^ "Heritage Park hit hard by flood upgrades to Glenmore Reservoir | Calgary Herald". Archived from the original on 2022-05-18. Retrieved 2023-10-09.

- ^ Dormer, Dave (2018-03-15). "Calgary sailors left high and dry by lowering of Glenmore Reservoir". CBC. Archived from the original on 2023-11-25.

- ^ All trivia points first appeared on the Idaho Public TV show Waterworks and were copied from the June 8, 2005 Calgary Herald.

- ^ "Bylaws related to the Glenmore Reservoir". City of Calgary. January 28, 2016. Archived from the original on February 13, 2016. Retrieved January 18, 2016.