The Wizard of Oz

| The Wizard of Oz | |

|---|---|

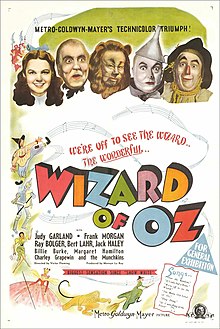

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Victor Fleming |

| Screenplay by | |

| Adaptation by |

|

| Based on | The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum |

| Produced by | Mervyn LeRoy |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Harold Rosson |

| Edited by | Blanche Sewell |

| Music by | Herbert Stothart |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Loew's Incorporated[1] |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 102 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2.8 million[3][4] |

| Box office | $29.7 million |

The Wizard of Oz is a 1939 American musical fantasy film produced by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM). Based on the 1900 novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum, it was primarily directed by Victor Fleming, who left production to take over the troubled Gone with the Wind. It stars Judy Garland, Frank Morgan, Ray Bolger, Bert Lahr, Jack Haley, Billie Burke, and Margaret Hamilton. Noel Langley, Florence Ryerson, and Edgar Allan Woolf received credit for the screenplay, while others made uncredited contributions. The music was composed by Harold Arlen and adapted by Herbert Stothart, with lyrics by Edgar "Yip" Harburg.

The Wizard of Oz is celebrated for its use of Technicolor, fantasy storytelling, musical score, and memorable characters.[5] It was a critical success and was nominated for five Academy Awards, including Best Picture, winning Best Original Song for "Over the Rainbow" and Best Original Score for Stothart; an Academy Juvenile Award was presented to Judy Garland.[6] It was on a preliminary list of submissions from the studios for an Academy Award for Cinematography (Color) but was not nominated.[7] While the film was sufficiently popular at the box office, it failed to make a profit until its 1949 re-release, earning only $3 million on a $2.7 million budget, making it MGM's most expensive production at the time.[3][8][9]

The 1956 television broadcast premiere of the film on CBS reintroduced the film to the public. According to the U.S. Library of Congress, it is the most seen film in movie history.[10][11] In 1989, it was selected by the Library of Congress as one of the first 25 films for preservation in the United States National Film Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant";[12][13] it is also one of the few films on UNESCO's Memory of the World Register.[14] The film was ranked second in Variety's inaugural 100 Greatest Movies of All Time list published in 2022.[15] It was among the top ten in the 2005 British Film Institute (BFI) list of 50 Films to be Seen by the Age of 14 and is on the BFI's updated list of 50 Films to be Seen by the Age of 15 released in May 2020.[16] The Wizard of Oz has become the source of many quotes referenced in contemporary popular culture. The film frequently ranks on critics' lists of the greatest films of all time and is the most commercially successful adaptation of Baum's work.[10][17]

Plot

[edit]

In rural Kansas, Dorothy Gale lives on a farm owned by her Uncle Henry and Aunt Em, and wishes she could be somewhere else. Dorothy's neighbor, Almira Gulch, who had been bitten by Dorothy's dog, Toto, obtains a sheriff's order authorizing her to seize Toto. Toto escapes and returns to Dorothy, who runs away to protect him. Professor Marvel, a charlatan fortune-teller, convinces Dorothy that Em is heartbroken, which prompts Dorothy to return home. She returns just as a tornado approaches the farm. Unable to get into the locked storm cellar, Dorothy takes cover in the farmhouse and is knocked unconscious. She seemingly awakens to find the house moving through the air, with her and Toto still inside it.

The house comes down in an unknown land, and Dorothy is greeted by a good witch named Glinda, who floats down in a bubble and explains that Dorothy has landed in Munchkinland in the Land of Oz, and that the Munchkins are celebrating because the house landed on the Wicked Witch of the East, killing her. Her sister, the Wicked Witch of the West, suddenly appears. Before she can seize her deceased sister's ruby slippers, Glinda magically transports them onto Dorothy's feet and tells her to keep them on. Because the Wicked Witch has no power in Munchkinland, she leaves, but swears vengeance upon Dorothy and Toto. Glinda tells Dorothy to follow the yellow brick road to the Emerald City, the home of the Wizard of Oz, as he might know how to help her return home. Glinda then floats away in the bubble.

Along the way, Dorothy meets the Scarecrow, who wants a brain; the Tin Man, who wants a heart; and the Cowardly Lion, who wants courage. The group reaches the Emerald City, despite the efforts of the Wicked Witch. The group is initially denied an audience with the Wizard by his guard, but the guard relents due to Dorothy's grief, and the four are led into the Wizard's chambers. The Wizard appears as a giant ghostly head and tells them he will grant their wishes if they bring him the Wicked Witch's broomstick.

During their quest, Dorothy and Toto are captured by flying monkeys and taken to the Wicked Witch, but the ruby slippers protect her, and Toto manages to escape, leading the Scarecrow, Tin Man, and Cowardly Lion to the castle. They free Dorothy, but are pursued and finally cornered by the Witch and her guards. The Witch taunts them and sets fire to the Scarecrow's arm. When Dorothy throws a bucket of water onto the Scarecrow, she inadvertently splashes the Witch, causing her to melt away.

The Witch's guards gratefully give Dorothy her broomstick, and the four return to the Wizard, but he tells them to return tomorrow. When Toto pulls back a curtain, the "Wizard" is revealed to be an ordinary man operating machinery that projects a ghostly image of his face. The four travelers confront the Wizard, who insists he is a good man at heart, but confesses to being a humbug. He then "grants" the wishes of Dorothy's three friends by giving them tokens to confirm that they have the qualities they sought.

The Wizard reveals that he, like Dorothy, is from Kansas and accidentally arrived in Oz in a hot air balloon. When he offers to take Dorothy back to Kansas with him aboard his balloon, she accepts, but Toto jumps off and Dorothy goes after him, and the balloon accidentally lifts off with just the Wizard aboard. Glinda reappears and tells Dorothy she always had the power to return to Kansas using the ruby slippers, but had to find that out for herself. After sharing a tearful farewell with her friends, Dorothy heeds Glinda's instructions by tapping her heels three times and repeating, "There's no place like home."

Dorothy awakens in her own bed in Kansas. She recounts her adventures, but Em says that she just had a bad dream. Dorothy tells Marvel and the farm hands that they were in Oz also, and they smile, humoring her. As Dorothy hugs Toto, she gratefully exclaims, "Oh, Auntie Em, there's no place like home!"

Cast

[edit]In the film's end credits, whenever a Kansas character has a counterpart in Oz, only the Kansas character is listed. For example, Frank Morgan is listed as playing Professor Marvel, but not the Wizard of Oz. The only Oz characters listed in the credits are Glinda and the Munchkins.

- Judy Garland as Dorothy Gale

- Frank Morgan as Professor Marvel and the Wizard of Oz, the Gatekeeper, the Carriage Driver, and the Guard at the Wizard's door

- Ray Bolger as "Hunk", a farmhand, and the Scarecrow

- Bert Lahr as "Zeke", a farmhand, and the Cowardly Lion

- Jack Haley as "Hickory", a farmhand, and the Tin Man

- Billie Burke as Glinda, the Good Witch of the North

- Margaret Hamilton as Almira Gulch and the Wicked Witch of the West

- Charley Grapewin as Uncle Henry

- Pat Walshe as Nikko

- Clara Blandick as Emily "Em" Gale

- Terry as Toto

- The Singer Midgets as The Munchkins (See Munchkin § Actors and actresses)

Uncredited

- Mitchell Lewis as the Winkie Guard Captain[18]

- Adriana Caselotti as the voice of Juliet in the Tin Man's song "If I Only Had a Heart"[19]

- Candy Candido as the voice of the angry apple tree[20][21]

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]Production on the film began when Walt Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) showed that films adapted from popular children's stories and fairytales could be successful.[22][23] In January 1938, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer bought the rights to L. Frank Baum's popular novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz from Samuel Goldwyn. Goldwyn had considered making the film as a vehicle for Eddie Cantor, who was under contract to Samuel Goldwyn Productions and whom Goldwyn wanted to cast as the Scarecrow.[23]

The script went through several writers and revisions.[24] Mervyn LeRoy's assistant, William H. Cannon, had submitted a brief four-page outline.[24] Because recent fantasy films had not fared well, he recommended toning down or removing the magical elements. In his outline, the Scarecrow was a man so stupid that the only employment open to him was scaring crows from cornfields, and the Tin Woodman was a criminal so heartless that he was sentenced to be placed in a tin suit for eternity. This torture softened him into somebody gentler and kinder.[24] Cannon's vision was similar to Larry Semon's 1925 film adaptation, in which the magical elements are absent.

Afterward, LeRoy hired screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz, who delivered a 17-page draft of the Kansas scenes. A few weeks later, Mankiewicz delivered a further 56 pages. LeRoy also hired Noel Langley and poet Ogden Nash to write separate versions of the story. None of these three knew about the others, and this was not an uncommon procedure. Nash delivered a four-page outline; Langley turned in a 43-page treatment and a full film script. Langley then turned in three more scripts, this time incorporating the songs written by Harold Arlen and Yip Harburg. Florence Ryerson and Edgar Allan Woolf submitted a script and were brought on board to touch up the writing. They were asked to ensure that the story stayed true to Baum's book. However, producer Arthur Freed was unhappy with their work and reassigned it to Langley.[25] During filming, Victor Fleming and John Lee Mahin revised the script further, adding and cutting some scenes. Haley and Lahr are also known to have written some of their dialogue for the Kansas sequence.

They completed the final draft of the script on October 8, 1938, following numerous rewrites.[26] Others who contributed to the adaptation without credit include Irving Brecher, Herbert Fields, Arthur Freed, Yip Harburg, Samuel Hoffenstein, Jack Mintz, Sid Silvers, Richard Thorpe, George Cukor and King Vidor. Only Langley, Ryerson, and Woolf were credited for the script.[23]

In addition, songwriter Harburg's son (and biographer) Ernie Harburg reported:

So anyhow, Yip also wrote all the dialogue in that time and the setup to the songs and he also wrote the part where they give out the heart, the brains, and the nerve, because he was the final script editor. And he – there was eleven screenwriters on that – and he pulled the whole thing together, wrote his own lines and gave the thing a coherence and unity which made it a work of art. But he doesn't get credit for that. He gets lyrics by E. Y. Harburg, you see. But nevertheless, he put his influence on the thing.[27]

Langley seems to have thought that a 1939 audience was too sophisticated to accept Oz as a straight-ahead fantasy; therefore, it was reconceived as a lengthy, elaborate dream sequence.[28][23] Because they perceived a need to attract a youthful audience by appealing to modern fads and styles, the score had featured a song called "The Jitterbug", and the script had featured a scene with a series of musical contests. A spoiled, selfish princess in Oz had outlawed all forms of music except classical music and operetta. The princess challenged Dorothy to a singing contest, in which Dorothy's swing style enchanted listeners and won the grand prize. This part was initially written for Betty Jaynes,[29] but was later dropped.

Another scene, which was removed before final script approval and never filmed, was an epilogue scene in Kansas after Dorothy's return. Hunk (the Kansan counterpart to the Scarecrow) is leaving for an agricultural college, and extracts a promise from Dorothy to write to him. The scene implies that romance will eventually develop between the two, which also may have been intended as an explanation for Dorothy's partiality for the Scarecrow over her other two companions. This plot idea was never totally dropped, and is especially noticeable in the final script when Dorothy, just before she is to leave Oz, tells the Scarecrow, "I think I'll miss you most of all."[30]

Much attention was given to the use of color in the production, with the MGM production crew favoring some hues over others. It took the studio's art department almost a week to settle on the shade of yellow used for the Yellow Brick Road.[31]

Casting

[edit]

Several actresses were reportedly considered for the part of Dorothy, including Shirley Temple from 20th Century Fox, at the time, the most prominent child star; Deanna Durbin, a relative newcomer, with a recognized operatic voice; and Judy Garland, the most experienced of the three. Officially, the decision to cast Garland was attributed to contractual issues.

Ray Bolger was originally cast as the Tin Man and Buddy Ebsen was to play the Scarecrow.[26] Bolger, however, longed to play the Scarecrow, as his childhood idol Fred Stone had done on stage in 1902; with that very performance, Stone had inspired him to become a vaudevillian in the first place. Now unhappy with his role as the Tin Man (reportedly claiming, "I'm not a tin performer; I'm fluid"), Bolger convinced producer Mervyn LeRoy to recast him in the part he so desired.[32] Ebsen did not object; after going over the basics of the Scarecrow's distinctive gait with Bolger (as a professional dancer, Ebsen had been cast because the studio was confident he would be up to the task of replicating the famous "wobbly-walk" of Stone's Scarecrow), he recorded all of his songs, went through all the rehearsals as the Tin Man and began filming with the rest of the cast.[10]

W. C. Fields was originally chosen for the title role of the Wizard (after Ed Wynn turned it down, considering the part "too small"), but the studio could not meet Fields' fee.[33] Wallace Beery lobbied for the role, but the studio refused to spare him during the long shooting schedule. Instead, another contract player, Frank Morgan, was cast on September 22.

Veteran vaudeville performer Pat Walshe was best known for his performance as various monkeys in many theater productions and circus shows. He was cast as Nikko, the head Winged Monkey, on September 28, traveling to MGM studios on October 3.

An extensive talent search produced over a hundred dwarves to play Munchkins; this meant that most of the film's Oz sequences would have to be shot before work on the Munchkinland sequence could begin. According to Munchkin actor Jerry Maren, the dwarves were each paid over $125 a week (equivalent to $2,700 today). Meinhardt Raabe, who played the coroner, revealed in the 1990 documentary The Making of the Wizard of Oz that the MGM costume and wardrobe department, under the direction of designer Adrian, had to design over 100 costumes for the Munchkin sequences. They photographed and cataloged each Munchkin in their costume so they could consistently apply the same costume and makeup each day of production.

Gale Sondergaard was originally cast as the Wicked Witch of the West, but withdrew from the role when the witch's persona shifted from sly and glamorous (thought to emulate the Evil Queen in Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs) to the familiar "ugly hag".[34] She was replaced on October 10, 1938, just three days before filming started, by MGM contract player Margaret Hamilton. Sondergaard said in an interview for a bonus feature on the DVD that she had no regrets about turning down the part. Sondergaard would go on to play a glamorous feline villainess in Fox's version of Maurice Maeterlinck's The Blue Bird in 1940.[35] Hamilton played a role remarkably similar to the Wicked Witch in the Judy Garland film Babes in Arms (1939).

According to Aljean Harmetz, the "gone-to-seed" coat worn by Morgan as the Wizard was selected from a rack of coats purchased from a second-hand shop. According to legend, Morgan later discovered a label in the coat indicating it had once belonged to Baum, Baum's widow confirmed this, and the coat was eventually presented to her. However, Baum biographer Michael Patrick Hearn says the Baum family denies ever seeing the coat or knowing of the story; Hamilton considered it a rumor concocted by the studio.[36]

Filming

[edit]Ebsen replaced by Haley

[edit]The production faced the challenge of creating the Tin Man's costume. Several tests were done to find the right makeup and clothes for Ebsen.[37] Ten days into the shoot, Ebsen suffered a toxic reaction after repeatedly inhaling the aluminum dust (which his daughter, Kiki Ebsen, has said the studio misrepresented as an "allergic reaction") in the aluminum powder makeup he wore, though he did recall taking a breath one night without suffering any immediate effects. He was hospitalized in critical condition and was subsequently forced to leave the project. In a later interview (included on the 2005 DVD release of The Wizard of Oz), he recalled that the studio heads appreciated the seriousness of his illness only after he was hospitalized. Filming halted while a replacement for him was sought.

No footage of Ebsen as the Tin Man has ever been released – only photos taken during filming and makeup tests. His replacement, Jack Haley, assumed Ebsen had been fired.[38] The makeup used for Haley was quietly changed to an aluminum paste, with a layer of clown white greasepaint underneath, in order to protect his skin. Although it did not have the same dire effect on Haley, he did at one point suffer an eye infection from it. To keep down on production costs, Haley only rerecorded "If I Only Had a Heart" and solo lines during "If I Only Had the Nerve" and the scrapped song "The Jitterbug"; as such, Ebsen's voice can still be heard in the remaining songs featuring the Tin Man in group vocals.

George Cukor's brief stint

[edit]LeRoy, after reviewing the footage and feeling Thorpe was rushing the production, adversely affecting the actors' performances, had Thorpe replaced. During reorganization on the production, George Cukor temporarily took over under LeRoy's guidance. Initially, the studio had made Garland wear a blonde wig and heavy "baby-doll" makeup, and she played Dorothy in an exaggerated fashion. Cukor changed Garland's and Hamilton's makeup and costumes, and told Garland to "be herself". This meant that all the scenes Garland and Hamilton had already completed had to be reshot. Cukor also suggested the studio cast Jack Haley, on loan from Fox, as the Tin Man.[39]

Victor Fleming, the main director

[edit]Cukor did not shoot any scenes for the film, but acted merely as a creative advisor to the troubled production. His prior commitment to direct Gone with the Wind required him to leave on November 3, 1938, when Victor Fleming assumed directorial responsibility. As director, Fleming chose not to shift the film from Cukor's creative realignment. Producer LeRoy had already expressed his satisfaction with the film's new course.

Production on the bulk of the Technicolor sequences was a long and exhausting process that ran for over six months, from October 1938 to March 1939. Most of the cast worked six days a week and had to arrive as early as 4 a.m. to be fitted with makeup and costumes, and often did not leave until 7 pm or later. Cumbersome makeup and costumes were made even more uncomfortable by the daylight-bright lighting the early Technicolor process required, which could heat the set to over 100 °F (38 °C), which also had the side effect of bringing the production's electricity bill to a staggering estimate of $225,000 (equivalent to $4,928,469 in 2023).[40] Bolger later said that the frightening nature of the costumes prevented most of the Oz principals from eating in the studio commissary;[41] and the toxicity of Hamilton's copper-based makeup forced her to eat a liquid diet on shoot days.[42] It took as many as twelve takes to have Toto run alongside the actors as they skipped down the Yellow Brick Road.

All the Oz sequences were filmed in three-strip Technicolor,[23][24] while the opening and closing credits, and the Kansas sequences, were filmed in black and white and colored in a sepia-tone process.[23] Sepia-tone film was also used in the scene where Aunt Em appears in the Wicked Witch's crystal ball. The film was not the first to use Technicolor, which was introduced in The Gulf Between (1917) as a two-color additive process, nor the first to use the three-color subtractive Technicolor Process 4, which made its live-action debut during a sequence in The Cat and the Fiddle (1934).[43]

In Hamilton's exit from Munchkinland, a concealed elevator was installed to lower her below stage level, as fire and smoke erupted to dramatize and conceal her exit. The first take ran well, but on the second take, the burst of fire came too soon. The flames set fire to her green, copper-based face paint, causing third-degree burns to her hands and face. She spent three months recuperating before returning to work.[44] Her green makeup had usually been removed with acetone due to its toxic copper content. Because of Hamilton's burns, makeup artist Jack Young removed the makeup with alcohol to prevent infection.[45]

On-set treatment and abuse allegations

[edit]In the decades since the film’s release, credible stories have come out indicating that Judy Garland endured extensive abuse during and before filming from various parties involved.[46][47][48][49] The studio went to extreme lengths to change her appearance, including binding her chest and giving her Benzedrine tablets to keep her weight down, along with uppers and downers that caused giggling fits. There were claims that various members of the cast pointed out her breasts and made other lewd comments. Victor Fleming slapped her during the Cowardly Lion's introduction scene when Garland could not stop laughing at Lahr's performance. Once the scene was done, Fleming, reportedly ashamed of himself, ordered the crew to punch him in the face. Garland, however, kissed him instead.[50][51] She was also forced to wear a cap on her teeth due to the fact some of her teeth were misaligned and also had to wear rubber discs on her nose to change its shape during filming.[52] Claims have been made in memoirs that the frequently drunk actors portraying the Munchkins propositioned and pinched her.[53][54][48][55] Garland said that she was groped by Louis B. Mayer.[46][56]

Special effects, makeup and costumes

[edit]Arnold Gillespie, the film's special effects director, employed several techniques.[37] Developing the tornado scene was especially costly. Gillespie used muslin cloth to make the tornado flexible, after a previous attempt with rubber failed. He hung the 35 ft (11 m) of muslin from a steel gantry and connected the bottom to a rod. By moving the gantry and rod, he was able to create the illusion of a tornado moving across the stage. Fuller's earth was sprayed from both the top and bottom using compressed air hoses to complete the effect. Dorothy's house was recreated using a model.[57] Stock footage of this tornado was later recycled for a climactic scene in the 1943 musical film Cabin in the Sky, directed by Judy Garland's eventual second husband Vincente Minnelli.[58]

The Cowardly Lion and Scarecrow masks were made of foam latex makeup created by makeup artist Jack Dawn. Dawn was one of the first to use this technique.[59][60] It took an hour each day to slowly peel Bolger's glued-on mask from his face, a process that eventually left permanent lines around his mouth and chin.[45][61]

The Tin Man's costume was made of leather-covered buckram, and the oil used to grease his joints was made from chocolate syrup.[62] The Cowardly Lion's costume was made from real lion skin and fur.[63] Due to the heavy makeup, Bert Lahr could only consume soup and milkshakes on break, which eventually made him sick. After a few months, Lahr put his foot down and requested normal meals along with makeup redos after lunch.[64][65] For the "horse of a different color" scene, Jell-O powder was used to color the white horses.[66] Asbestos was used to achieve some of the special effects, such as the witch's burning broomstick and the fake snow that covers Dorothy as she sleeps in the field of poppies.[67][68]

Music

[edit]

The Wizard of Oz is famous for its musical selections and soundtrack. Its songs were composed by Harold Arlen, with lyrics by E. Y. "Yip" Harburg. They won the Academy Award for Best Original Song for "Over the Rainbow". The song ranks first in the AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs and the Recording Industry Association of America's "365 Songs of the Century".

MGM composer Herbert Stothart, a well-known Hollywood composer and songwriter, won the Academy Award for Best Original Score.

Georgie Stoll was associate conductor, and screen credit was given to George Bassman, Murray Cutter, Ken Darby and Paul Marquardt for orchestral and vocal arrangements. (As usual, Roger Edens was also heavily involved as an unbilled musical associate to Freed.)[citation needed]

The songs were recorded in the studio's scoring stage before filming. Several of the recordings were completed while Ebsen was still with the cast. Although he had to be dropped from the cast because of a dangerous reaction to his aluminum powder makeup, his singing voice remained on the soundtrack (as mentioned in the notes for the CD Deluxe Edition). He can be heard in the group vocals of "We're Off to See the Wizard".

Bolger's original recording of "If I Only Had a Brain" was far more sedate than the version in the film. During filming, Cukor and LeRoy decided a more energetic rendition better suited Dorothy's initial meeting with the Scarecrow, and it was rerecorded. The original version was considered lost until a copy was discovered in 2009.[69]

Songs

[edit]All lyrics are written by E. Y. Yip Harburg; all music is composed by Harold Arlen

Deleted songs

[edit]

Some musical pieces were filmed and deleted later, in the editing process.

The song "The Jitterbug", written in a swing style, was intended for a sequence where the group journeys to the Witch's castle. Owing to time constraints, it was cut from the final theatrical version. The film footage of the song has been lost, although silent home-film footage of rehearsals has survived. The audio recording of the song was preserved, and was included in the two-CD Rhino Records deluxe edition of the soundtrack, as well as on the film's VHS and DVD editions. A reference to "The Jitterbug" remains in the film: The Witch tells her flying monkeys that they should have no trouble apprehending Dorothy and her friends because "I've sent a little insect on ahead to take the fight out of them."[70]

Another musical number cut before release came right after the Wicked Witch of the West was melted and before Dorothy and her friends returned to the Wizard. This was a reprise of "Ding-Dong! The Witch Is Dead" (blended with "We're Off to See the Wizard" and "The Merry Old Land of Oz") with the lyrics altered to "Hail! Hail! The witch is dead!" This started with the Witch's guard saying "Hail to Dorothy! The Wicked Witch is dead!" and dissolved to a huge celebration by the citizens of the Emerald City, who sang the song as they accompanied Dorothy and her friends to the Wizard. Today, the film of this scene is also lost, and only a few stills survive, along with a few seconds of footage used on several reissue trailers. The entire audio track was preserved and is included on the two-CD Rhino Record "deluxe" soundtrack edition.[71]

Garland was to sing a brief reprise of "Over the Rainbow" while Dorothy was trapped in the Witch's castle, but it was cut because it was considered too emotionally intense. Because Garland sang the reprise live on set, only the underscoring from the final edit survives. However, the on-set audio of the scene when it was originally filmed under Richard Thorpe still exists and was included as an extra in all home media releases from 1993 onward. The Deluxe Edition soundtrack marries the singing from the Thorpe take to the underscoring from the Fleming version to approximate what this would have sounded like.[72]

Underscoring

[edit]Extensive edits in the film's final cut removed vocals from the last portion of the film. However, the film was fully underscored, with instrumental snippets from the film's various leitmotifs throughout. There was also some recognizable classical and popular music, including:

- Excerpts from Schumann's "The Happy Farmer", at several points early in the film, including the opening scene when Dorothy and Toto hurry home after their encounter with Miss Gulch; when Toto escapes from her; and when the house "rides" the tornado.

- An excerpt of Mendelssohn's Scherzo in E minor, Op. 16, No. 2, when Toto escapes from the Witch's castle.

- An excerpt of Mussorgsky's "Night on Bald Mountain", when Dorothy, the Scarecrow, the Tin Man and the Cowardly Lion try to escape from the Witch's castle.

- "In the Shade of the Old Apple Tree", when Dorothy and the Scarecrow discover the anthropomorphic apple trees.

- "Gaudeamus Igitur", as the Wizard presents awards to the group.

- "Home! Sweet Home!", in part of the closing scene, at Dorothy's house in Kansas.

(This list is excerpted from the liner notes of the Rhino Records collection.)

Post-production

[edit]Principal photography concluded with the monochromatic Kansas sequences on March 16, 1939. When Victor Fleming was called away to replace George Cukor as director of Gone with the Wind, veteran director King Vidor agreed to direct Oz during its final ten days of principal production. This included the bulk of the Kansas scenes, including Garland's performance of "Over the Rainbow."[73]

Reshoots and pickup shots were done through April and May and into June, under the direction of producer LeRoy. When the "Over the Rainbow" reprise was removed after subsequent test screenings in early June, Garland had to be brought back to reshoot the "Auntie Em, I'm frightened!" scene without the song. The footage of Blandick's Aunt Em, as shot by Vidor, had already been set aside for rear-projection work, and was reused.

After Hamilton's severe injuries with the Munchkinland elevator, she refused to do the pickups for the scene where she flies on a broomstick that billows smoke, so LeRoy had stunt double Betty Danko perform instead. Danko was severely injured when the smoke mechanism malfunctioned.[74]

At this point, the film began a long, arduous post-production. Herbert Stothart composed the film's background score, while A. Arnold Gillespie perfected the special effects, including many of the rear-projection shots. The MGM art department created matte paintings for many scene backgrounds.

A significant innovation planned for the film was the use of stencil printing for the transition to Technicolor. Each frame was to be hand-tinted to maintain the sepia tone. However, it was abandoned because it was too expensive and labor-intensive, and MGM used a simpler, less expensive technique: During the May reshoots, the inside of the farmhouse was painted sepia, and when Dorothy opens the door, it is not Garland, but her stand-in, Bobbie Koshay, wearing a sepia gingham dress, who then backs out of frame. Once the camera moves through the door, Garland steps back into frame in her bright blue gingham dress (as noted in DVD extras), and the sepia-painted door briefly tints her with the same color before she emerges from the house's shadow, into the bright glare of the Technicolor lighting. This also meant that the reshoots provided the first proper shot of Munchkinland. If one looks carefully, the brief cut to Dorothy looking around outside the house bisects a single long shot, from the inside of the doorway to the pan-around that finally ends in a reverse-angle as the ruins of the house are seen behind Dorothy and she comes to a stop at the foot of the small bridge.

Test screenings of the film began on June 5, 1939.[75] Oz initially ran nearly two hours long. In 1939, the average film ran for about 90 minutes. LeRoy and Fleming knew they needed to cut at least 15 minutes to get the film down to a manageable running time. Three sneak previews in San Bernardino, Pomona and San Luis Obispo, California, guided LeRoy and Fleming in the cutting. Among the many cuts were "The Jitterbug" number, the Scarecrow's elaborate dance sequence following "If I Only Had a Brain", reprises of "Over the Rainbow" and "Ding-Dong! The Witch Is Dead", and a number of smaller dialogue sequences. This left the final, mostly serious portion of the film with no songs, only the dramatic underscoring.

"Over the Rainbow" was almost deleted. MGM felt that it made the Kansas sequence too long, as well as being far over the heads of the target audience of children. The studio also thought that it was degrading for Garland to sing in a barnyard. LeRoy, uncredited associate producer Arthur Freed and director Fleming fought to keep it in, and they eventually won. The song went on to win the Academy Award for Best Original Song, and came to be identified so strongly with Garland herself that she made it her signature song.

After the preview in San Luis Obispo in early July, the film was officially released in August 1939 at its current 101-minute running time.

Release

[edit]Original theatrical run

[edit]

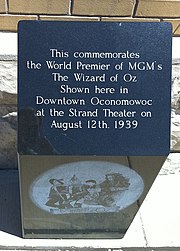

The film premiered at the Orpheum Theatre in Green Bay, Wisconsin, on August 10, 1939,[76] although this is disputed by the August 23, 1939 issue of “The Exhibitor,” which places the debut a day earlier in New Bedford, Massachusetts. [77] The first sneak preview was held in San Bernardino, California.[78] The film was previewed in three test markets: Kenosha, Wisconsin, on August 11, 1939; Dennis, Massachusetts, also on August 11;[79][80] and the Strand Theatre in Oconomowoc, Wisconsin, on August 12.[81]

The Hollywood premiere was on August 16, 1939,[80] following a preview the night before at Grauman's Chinese Theatre.[82] The New York City premiere, held at Loew's Capitol Theatre on August 17, 1939, was followed by a live performance with Garland and her frequent film co-star Mickey Rooney. They continued to perform there after each screening for a week. Garland extended her appearance for two more weeks, partnered with Rooney for a second week and with Oz co-stars Ray Bolger and Bert Lahr for the third and final week. The film opened nationwide on August 25, 1939.

Television

[edit]MGM sold CBS the rights to televise the film for $225,000 (equivalent to $1.93 million in 2023) per broadcast.[83] It was first shown on television on November 3, 1956, as the last installment of the Ford Star Jubilee.[84] It was a ratings success, with a Nielsen rating of 33.9 and an audience share of 53%.[85]

It was repeated on December 13, 1959, and gained an even larger television audience, with a Nielsen rating of 36.5 and an audience share of 58%.[85] It became an annual television tradition.

The UK television premiere was on Christmas Day, 1975, on BBC1. The estimated UK television audience was 20 million.[86]

Home media

[edit]On October 25, 1980, the film was released on videocassette (in both VHS and Betamax format) by MGM/CBS Home Video.[87] All current home video releases are by Warner Home Video (via current rights holder Turner Entertainment).

The film's first LaserDisc release was in 1983. In 1989, there were two releases for the 50th anniversary, one from Turner and one from The Criterion Collection, with a commentary track. LaserDiscs came out in 1991 and 1993, and the final LaserDisc was released September 11, 1996.[88]

The film was released on the CED format once, in 1982, by MGM/UA Home Video.[89] It has also been released multiple times outside of the North American and European markets, in Asia, in the Video CD format.

The first DVD release was on March 26, 1997, by MGM/Turner. It contained no special features or supplements. On October 19, 1999, The Wizard of Oz was re-released by Warner Bros. to celebrate the film's 60th anniversary, with its soundtrack presented in a new 5.1 surround sound mix. The DVD also contained a behind-the-scenes documentary, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz: The Making of a Movie Classic, produced in 1990 and hosted by Angela Lansbury, which was originally shown on television immediately following the 1990 telecast of the film. It had been featured in the 1993 "Ultimate Oz" LaserDisc release. Outtakes, the deleted "Jitterbug" musical number, clips of pre-1939 Oz adaptations, trailers, newsreels, and a portrait gallery were also included, as well as two radio programs of the era publicizing the film.

In 2005, two DVD editions were released, both featuring a newly restored version of the film with an audio commentary and an isolated music and effects track. One of the two DVD releases was a "Two-Disc Special Edition", featuring production documentaries, trailers, outtakes, newsreels, radio shows and still galleries. The other set, a "Three-Disc Collector's Edition", included these features, as well as the digitally restored 80th-anniversary edition of the 1925 feature-length silent film version of The Wizard of Oz, other silent Oz adaptations and a 1933 animated short version.

The film was released on Blu-ray on September 29, 2009, for its 70th anniversary, in a four-disc "Ultimate Collector's Edition", including all the bonus features from the 2005 Collector's Edition DVD, new bonus features about Victor Fleming and the surviving Munchkins, the telefilm The Dreamer of Oz: The L. Frank Baum Story, and the miniseries MGM: When the Lion Roars. For this edition, Warner Bros. commissioned a new transfer from the original negatives at 8K resolution. The restoration job was given to Prime Focus World.[90] This restored version also features a lossless 5.1 Dolby TrueHD audio track.[91]

On December 1, 2009,[92] three Blu-ray discs of the Ultimate Collector's Edition were repackaged as a less expensive "Emerald Edition". An Emerald Edition four-disc DVD arrived the following week. A single-disc Blu-ray, containing the restored movie and all the extra features of the two-disc Special Edition DVD, became available on March 16, 2010.[93]

In 2013, the film was re-released on DVD, Blu-ray, Blu-ray 3D and UltraViolet for the 90th anniversary of Warner Bros. and the 75th anniversary of the film.[94][95]

Many special editions were released in 2013 in celebration of the film's 75th anniversary, including one exclusively by Best Buy (a SteelBook of the 3D Blu-ray) and another by Target stores that came with a keepsake lunch bag.[96][97]

The film was issued on 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray on October 29, 2019, featuring both a Dolby Vision and an HDR10+ grading from an 8K transfer.[98] Another 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray release, including collective replica items from the film's Hollywood premiere was released on November 5, 2024, to celebrate the film's 85th anniversary.[99]

Re-releases

[edit]

Although the 1949 re-issue used sepia tone, the 1955 re-issue showed the Kansas sequences in black and white instead, a practice that continued on television broadcasts and home releases until the 50th anniversary VHS release in 1989.[100]

The MGM "Children's Matinees" series re-released the film twice, in both 1970 and 1971.[101] It was for this release that the film received a G rating from the MPAA.

For the film's 60th anniversary, Warner Bros. released a "Special Edition" on November 6, 1998, digitally restored with remastered audio.

In 2002, the film had a very limited re-release in U.S. theaters, earning only $139,905.[102]

On September 23, 2009, the film was re-released in select theaters for a one-night-only event in honor of its 70th anniversary and as a promotion for various new disc releases later in the month. An encore of this event took place in theaters on November 17, 2009.[103]

An IMAX 3D theatrical re-release played at 300 theaters in North America for one week only beginning September 20, 2013, as part of the film's 75th anniversary.[94] Warner Bros. spent $25 million on advertising. The studio hosted a premiere of the film's first IMAX 3D release on September 15, 2013, in Hollywood at the newly remodeled TCL Chinese Theatre (formerly Grauman's Chinese Theatre, the site of the film's Hollywood premiere). It was the first motion picture to play at the new theater and served as the grand opening of Hollywood's first 3D IMAX screen. It was also shown as a special presentation at the 2013 Toronto International Film Festival.[104] This re-release grossed $5.6 million at the North American box office.[105]

In 2013, in preparation for its IMAX 3D release, the film was submitted to the MPAA for re-classification. According to MPAA rules, a film that has been altered in any way from its original version must be submitted for re-classification, and the 3-D conversion fell within that guideline. The 3D version received a PG rating for "Some scary moments", although no change was made to the film's original story content. The 2D version still retains its G rating.[106]

The film was re-released on January 11 and 14, 2015, as part of the "TCM Presents" series by Turner Classic Movies.[107]

The film was re-released by Fathom Events through "TCM Big Screen Classics" on January 27, 29, 30, 2019, and February 3 and 5, 2019, as part of its 80th anniversary. It also had a one-week theatrical engagement in Dolby Cinema on October 25, 2019, to commemorate the anniversary.[108]

The film returned to theaters on June 5 and 6, 2022, to celebrate Judy Garland's 100th birthday.[109]

To celebrate the 85th anniversary, "Fathom Big Screen Classics" (now taken over from TCM) released the film January 28, 29 and 31, 2024, with a special introduction by Leonard Maltin and a preshow trivia game hosted by "Oz Vlog" host Victoria Calamito.[110]

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]The Wizard of Oz received universal acclaim upon its release.[111][112] Writing for The New York Times, Frank Nugent considered the film a "delightful piece of wonder-working which had the youngsters' eyes shining and brought a quietly amused gleam to the wiser ones of the oldsters. Not since Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs has anything quite so fantastic succeeded half so well."[113] Nugent had issues with some of the film's special effects:

with the best of will and ingenuity, they cannot make a Munchkin or a Flying Monkey that will not still suggest, however vaguely, a Singer's Midget in a Jack Dawn masquerade. Nor can they, without a few betraying jolts and split-screen overlappings, bring down from the sky the great soap bubble in which Glinda rides and roll it smoothly into place.[113]

According to Nugent, "Judy Garland's Dorothy is a pert and fresh-faced miss with the wonder-lit eyes of a believer in fairy tales, but the Baum fantasy is at its best when the Scarecrow, the Tin Man, and the Lion are on the move."[113]

Writing in Variety, John C. Flinn predicted that the film was "likely to perform some record-breaking feats of box-office magic," noting, "Some of the scenic passages are so beautiful in design and composition as to stir audiences by their sheer unfoldment." He also called Garland "an appealing figure" and the musical numbers "gay and bright".[114]

Harrison's Reports wrote, "Even though some persons are not interested in pictures of this type, it is possible that they will be eager to see this picture just for its technical treatment. The performances are good, and the incidental music is of considerable aid. Pictures of this caliber bring credit to the industry."[115]

Film Daily wrote:

Leo the Lion is privileged to herald this one with his deepest roar—the one that comes from way down—for seldom if indeed ever has the screen been so successful in its approach to fantasy and extravaganza through flesh-and-blood... handsomely mounted fairy story in Technicolor, with its wealth of humor and homespun philosophy, its stimulus to the imagination, its procession of unforgettable settings, its studding of merry tunes should click solidly at the box-office.[116]

Some reviews were less positive. Some moviegoers felt that the 16-year-old Garland was slightly too old to play the little girl who Baum intended his Dorothy to be. Russell Maloney of The New Yorker wrote that the film displayed "no trace of imagination, good taste, or ingenuity" and declared it "a stinkeroo",[117] while Otis Ferguson of The New Republic wrote: "It has dwarfs, music, Technicolor, freak characters, and Judy Garland. It can't be expected to have a sense of humor, as well – and as for the light touch of fantasy, it weighs like a pound of fruitcake soaking wet."[118] Still, the film placed seventh on Film Daily's year-end nationwide poll of 542 critics naming the best films of 1939.[119]

Box office

[edit]According to MGM records, during the film's initial release, it earned $2,048,000 in the U.S. and $969,000 in other countries throughout the world, for total earnings of $3,017,000. However, its high production cost, plus the costs of marketing, distribution, and other services, resulted in a loss of $1,145,000 for the studio.[3] It did not show what MGM considered a profit until a 1949 re-release earned an additional $1.5 million (about $15 million in 2023). Christopher Finch, author of the Judy Garland biography Rainbow: The Stormy Life of Judy Garland, wrote: "Fantasy is always a risk at the box office. The film had been enormously successful as a book, and it had also been a major stage hit, but previous attempts to bring it to the screen had been dismal failures." He also wrote that after the film's success, Garland signed a new contract with MGM giving her a substantial increase in salary, making her one of the top ten box-office stars in the United States.[120]

The film was also re-released domestically in 1955. Subsequent re-releases between 1989 and 2019 have grossed $25,173,032 worldwide,[4] for a total worldwide gross of $29,690,032.

Legacy

[edit]The film was not the first to utilize color, but the way in which the film was saturated with Technicolor proved that color could provide a magical element to fantasy films. The film is iconic for its symbols such as the Yellow Brick Road, ruby slippers, Emerald City, Munchkins, and the phrase "There's no place like home".[121] The film became a global phenomenon and is still well known today.[122]

Roger Ebert chose it as one of his Great Films, writing that "The Wizard of Oz has a wonderful surface of comedy and music, special effects and excitement, but we still watch it six decades later because its underlying story penetrates straight to the deepest insecurities of childhood, stirs them and then reassures them."[123]

In his 1992 critique of the film for the British Film Institute, author Salman Rushdie acknowledged its effect on him, noting "The Wizard of Oz was my very first literary influence".[124] In "Step Across This Line", he wrote: "When I first saw The Wizard of Oz, it made a writer of me."[125] His first short story, written at the age of 10, was titled "Over the Rainbow".[125]

In a 2009 retrospective article about the film, San Francisco Chronicle film critic and author Mick LaSalle declared:

...the entire Munchkinland sequence, from Dorothy's arrival in Oz to her departure on the yellow brick road, has to be one of the greatest in cinema history – a masterpiece of set design, costuming, choreography, music, lyrics, storytelling, and sheer imagination.[126]

In 2018, it was named the "most influential film of all time" as the result of a study conducted by the University of Turin to measure the success and significance of 47,000 films from around the world using data from readers and audience polls, as well as internet sources such as IMDb. It would top the list in their study, followed by the Star Wars franchise, Psycho (1960), King Kong (1933) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) rounding out the top 5.[127]

On the film review aggregator site Rotten Tomatoes, The Wizard of Oz has a 98% rating based on 169 reviews, with an average score of 9.4/10. Its critical consensus reads, "An absolute masterpiece whose groundbreaking visuals and deft storytelling are still every bit as resonant, The Wizard of Oz is a must-see film for young and old."[128] At Metacritic, which assigns a normalized rating to reviews, the film received a score of 92 out of 100, based on 30 reviews, indicating "universal acclaim".[129]

The film was included by the Vatican in a list of important films compiled in 1995, under the category of "Art".[130]

Accolades

[edit]Academy Awards

[edit]| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Nominee(s) | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | February 29, 1940 | Outstanding Production | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer | Nominated | [131] |

| Best Art Direction | Cedric Gibbons and William A. Horning | Nominated | |||

| Best Original Score | Herbert Stothart | Won | |||

| Best Original Song | "Over the Rainbow" Music by Harold Arlen; Lyrics by E. Y. Harburg |

Won | |||

| Best Special Effects | A. Arnold Gillespie and Douglas Shearer | Nominated | |||

| Academy Juvenile Award | Judy Garland For her outstanding performance as a screen juvenile during the past year. (She was jointly awarded for her performances in Babes in Arms and The Wizard of Oz). |

Honorary |

American Film Institute lists

[edit]The American Film Institute (AFI) has compiled various lists which include this film or its elements.

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies – No. 6

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills – No. 43

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains:

- Wicked Witch of the West – No. 4 Villain

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs:

- "Over the Rainbow" – No. 1

- "Ding-Dong! The Witch Is Dead" – No. 82

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes:

- "Toto, I've a feeling we're not in Kansas anymore." (Dorothy Gale) – No. 4

- "There's no place like home." (Dorothy) – No. 23

- "I'll get you, my pretty – and your little dog, too!" (Wicked Witch of the West) – No. 99

- AFI's Greatest Movie Musicals – No. 3

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers – No. 26

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) – No. 10

- AFI's 10 Top 10 – No. 1 Fantasy film[132]

Other honors

[edit]- 1989: The film was one of the inaugural group of 25 films added to the National Film Registry list.[12][133]

- 1999: Rolling Stone's 100 Maverick Movies – No. 20.[134]

- 1999: Entertainment Weekly's 100 Greatest Films – No. 32.[135]

- 2000: The Village Voice's 100 Best Films of the 20th Century – No. 14.[136]

- 2002: Nominated – 1939 Palme d'Or

- 2002: Sight & Sound's Greatest Film Poll of Directors – No. 41.[137]

- 2005: Total Film's 100 Greatest Films – No. 83[138]

- 2005: The British Film Institute ranked it second on its list of the 50 films you should see by the age of 14, after Spirited Away.[citation needed]

- 2006: The film placed 86th on Bravo's 100 Scariest Movie Moments.[139]

- 2007: It topped Total Film's 23 Weirdest Films.[140]

- 2007: The film was listed on UNESCO's Memory of the World Register.[141]

- 2007: The Observer ranked the film's songs and music at the top of its list of 50 greatest film soundtracks.[142]

- 2020: The British Film Institute changed its list to "50 films to see by age 15 – Updated"[143] calling Oz "The most wonderful of musicals"

- 2022: The film was ranked 2nd in Variety's inaugural list of The 100 Greatest Movies of All Time.[15]

- 2023: The film was ranked 5th in Parade's list of The 100 Best Movies of All Time.[144]

- 2023: The film was ranked 4th in Comic Book Resources' list of The Best Movies of All Time.[145]

- 2024: The film was ranked 7th on IndieWire's list of The 63 Best Movie Musicals of All Time.[146]

Sequels and reinterpretations

[edit]An official 1972 sequel, the animated Journey Back to Oz, featuring the voice of Judy Garland's daughter Liza Minnelli was produced to commemorate the original film's 35th anniversary.[147]

The Wiz, a musical based on the novel, opened in 1974 in Baltimore and in 1975 with a new cast on Broadway. It went on to win seven Tony Awards, including Best Musical. A film adaptation was released in 1978.

In 1975, a comic book adaptation of the film titled MGM's Marvelous Wizard of Oz was released. It was the first co-production between DC Comics and Marvel Comics. Marvel planned a series of sequels based on the subsequent novels. The first, The Marvelous Land of Oz, was published later that year. The next, The Marvelous Ozma of Oz was expected to be released the following year but never came to be.[148]

In 1985, Walt Disney Productions released the live-action fantasy film Return to Oz, starring Fairuza Balk in her film debut as a young Dorothy Gale[149] and based on The Marvelous Land of Oz (1904) and Ozma of Oz (1907). With a darker story, it fared poorly with critics unfamiliar with the Oz books and was not successful at the box office, although it has since become a popular cult film, with many considering it a more loyal and faithful adaptation of what L. Frank Baum envisioned.[150][151]

The Broadway musical Wicked premiered in 2003, and is based on the film and original novel. It has since gone on to become the second-highest grossing Broadway musical of all time, and won three Tony Awards, seven Drama Desk Awards, and a Grammy Award. A two-part film adaptation of the musical, directed by Jon M. Chu, entered development at Universal Pictures in 2004. The first film was released on November 22, 2024, and the second, Wicked: For Good, is scheduled for November 21, 2025.

Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice produced a stage musical of the same name, which opened in 2011 at the West End's London Palladium.

An animated film called Tom and Jerry and the Wizard of Oz was released in 2011 by Warner Home Video, incorporating Tom and Jerry into the story as Dorothy's "protectors".[152] A sequel titled Tom and Jerry: Back to Oz was released on DVD on June 21, 2016.[153]

In 2013, Walt Disney Pictures released a "spiritual prequel" titled Oz the Great and Powerful. It was directed by Sam Raimi and starred James Franco, Mila Kunis, Rachel Weisz and Michelle Williams. It was the second film based on Baum's Oz series to be produced by Disney, after Return to Oz. It was a commercial success but received a mixed reception from critics.[154][155]

In 2014, independent film company Clarius Entertainment released a big-budget animated musical film, Legends of Oz: Dorothy's Return,[156] which follows Dorothy's second trip to Oz. The film fared poorly at the box office and was received negatively by critics, largely for its plot and unmemorable musical numbers.

In February 2021, New Line Cinema, Temple Hill Entertainment and Wicked producer Marc Platt announced that a new film version of the original book is in the works with Watchmen's Nicole Kassell slated to direct the reimagining, which will have the option to include elements from the 1939 film.[157]

In August 2022, it was announced that Kenya Barris would write and direct a modern remake.[158][159] In January 2024, Barris confirmed that he finished penning the script and remarked "The original Wizard of Oz took place during the Great Depression and it was about self-reliance and what people were going through, I think this is the perfect time to switch the characters and talk about what someone imagines their life could be. It's ultimately a hero's journey, someone thinks something's better than where they're at, and they go and realize that where they're at is where they should be. I want people to be proud and happy about where they're from. But I want the world to take a look at it and I hope that will come through." This involved changing the time period to the present day and changing Dorothy's home from Kansas to the Bottoms of Inglewood, California.[160]

The 2024 marketing campaign for season 22 of American Idol is directly themed after this film, complete with a commercial featuring Ryan Seacrest and the judges Katy Perry, Lionel Richie and Luke Bryan dressed as Tin Man, Dorothy, Cowardly Lion and Scarecrow following the "Golden Ticket Road" to Hollywood. This was to reflect the show's plans to visit the judges' hometowns throughout the season.[161][162]

Cultural impact

[edit]According to the US Library of Congress exhibition The Wizard of Oz: an American Fairy Tale (2010):[163]

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is America's greatest and best-loved home-grown fairytale. The first totally American fantasy for children, it is one of the most-read children's books ... Despite its many particularly American attributes, including a wizard from Omaha, [the 1939 film adaptation] has universal appeal...[164] Because of its many television showings between 1956 and 1974, it has been seen by more viewers than any other movie".[11]

In 1977, Aljean Harmetz wrote The Making of The Wizard of Oz, a detailed description of the creation of the film based on interviews and research; it was updated in 1989.[165]

Ruby slippers

[edit]

Because of their iconic stature,[166] the ruby slippers worn by Judy Garland in the film are now among the most treasured and valuable film memorabilia in movie history.[167] Dorothy actually wore Silver Shoes in the book series, but the color was changed to ruby to take advantage of the new Technicolor process. Adrian, MGM's chief costume designer, was responsible for the final design. Five known pairs of the slippers exist.[168] Another, differently styled pair, not used in the film, was sold at auction by actress Debbie Reynolds for $510,000 (not including the buyer's premium) in June 2011.[169] One pair of Judy Garland's ruby slippers are located in Washington D.C. at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.[170]

In 2005, one of the pairs of the ruby slippers was stolen while on loan to the Judy Garland Museum in Garland's hometown. They were recovered in an FBI sting operation in 2018. At the time they were stolen, the slippers were insured for $1 million. That pair was sold in an auction, in December, 2024 for over $32 million.[171] That is more than $26 million above the previous highest price ever paid for a piece of entertainment memorabilia.[172] In 2023, the slipper thief was indicted with one count of a major artwork theft. The shoes are one of four authentic pairs that are still intact.[173]

Dorothy's dress and other costumes

[edit]In July 2021, Catholic University of America reported that a dress worn by Dorothy, believed to have been given to Rev. Gilbert Hartke by Mercedes McCambridge as a gift in 1973, was found in the university's Hartke Building after being missing for many years. The university said an expert on the movie's memorabilia at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History said five other dresses apparently worn by Judy Garland were "probably authentic". The dress found at the university had characteristics shared by the other five, including a "secret pocket" for Dorothy's handkerchief, and Garland's name written in a specific style. The university said the dress would be stored in Special Collections.

Another of the dresses sold at auction in 2015 for nearly $1.6 million.[174] Many other costumes have fetched six-figure prices as memorabilia. See List of film memorabilia.

Theme park attractions

[edit]The Wizard of Oz has a presence at the Disney Parks and Resorts. The film had its own scene at The Great Movie Ride at Disney Hollywood Studios at Walt Disney World Resort, and is also represented in miniature at Disneyland and at Disneyland Paris as part of the Storybook Land Canal Boats attraction in Fantasyland.[175][176] The Great Movie Ride was shut down in 2017.[177]

On July 20, 2022, it was announced that Warner Bros. Movie World would be adding a new precinct based on the 1939 film The Wizard Of Oz. It is to feature two coasters manufactured by Vekoma and will open in 2024.[178]

See also

[edit]- The Dark Side of the Rainbow

- Friend of Dorothy

- List of cult films

- Political interpretations of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

- Wizard of Oz festival

- The Wiz (musical)

- The Wiz (film)

References

[edit]- ^ The Wizard of Oz at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- ^ "The Wizard Of Oz" (Cinema). BBFC. British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved September 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c The Eddie Mannix Ledger, Los Angeles: Margaret Herrick Library, Center for Motion Picture Study.

- ^ a b "The Wizard of Oz (1939)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on October 25, 2019. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

- ^ "The Technicolor world of Oz". americanhistory.si.edu. June 7, 2010. Retrieved October 24, 2024.

- ^ CineVue (November 9, 2022). "The enduring legacy of The Wizard of Oz". CineVue. Retrieved October 24, 2024.

- ^ "Academy Awards database: 12th award show search results". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

- ^ Nugent, Frank S. (August 18, 1939). "The Screen in Review; 'The Wizard of Oz,' Produced by the Wizards of Hollywood, Works Its Magic on the Capitol's Screen – March of Time Features New York at the Music Hall at the Palace". Retrieved August 15, 2014.

- ^ King, Susan (March 11, 2013). "How did 'Wizard of Oz' fare on its 1939 release?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- ^ a b c Fricke, John (1989). The Wizard of Oz: The Official 50th Anniversary Pictorial History. New York: Warner Books. ISBN 978-0-446-51446-0.

- ^ a b "To See The Wizard Oz on Stage and Film". Library of Congress. December 15, 2010. Archived from the original on September 29, 2018. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ a b "Complete National Recording Registry Listing – National Recording Preservation Board – Library of Congress". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on January 7, 2017. Retrieved March 18, 2018.

- ^ "Film Registry Picks First 25 Movies". Los Angeles Times. Washington, D.C. September 19, 1989. Archived from the original on May 5, 2020. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ "The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming 1939), produced by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer". UNESCO Memory of the World Programme. Archived from the original on August 5, 2009. Retrieved September 7, 2009.

- ^ a b Debruge, Peter; Gleiberman, Owen; Kennedy, Lisa; Kiang, Jessica; Laffly, Tomris; Lodge, Guy; Nicholson, Amy (December 21, 2022). "The 100 Greatest Movies of All Time". Variety. Retrieved December 23, 2022.

- ^ "50 films to see by age 15". British Film Institute. May 6, 2020. Archived from the original on May 28, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies". www.afi.com. Archived from the original on May 15, 2016. Retrieved August 9, 2017.

- ^ Scarfone, Jay; Stillman, William (2018). The Road to Oz: The Evolution, Creation, and Legacy of a Motion Picture Masterpiece. Lyons Press. ISBN 978-1493035328.

- ^ Sibley, Brian (February 10, 1997). "Obituary: Adriana Caselotti". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on January 14, 2013. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- ^ DiNardo, John (June 21, 1974). "Fair 'Promoters' Having Fun". The Times Record. Troy, New York. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Wittman, Bob (May 21, 1999). "Candido (continued)". The Morning Call. Allentown, Pennsylvania. p. 29 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Fricke, John; Scarfone, Jay; Stillman, William (1989). The Wizard of Oz: The Official 50th Anniversary Pictorial History. New York, NY: Warner Books, Inc. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-446-51446-0.

- ^ a b c d e f The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, the Making of a Movie Classic (1990). CBS Television, narrated by Angela Lansbury. Co-produced by John Fricke and Aljean Harmetz.

- ^ a b c d Aljean Harmetz (2004). The Making of The Wizard of Oz. Hyperion. ISBN 0-7868-8352-9. See the Chapter "Special Effects.

- ^ Coan, Stephen (December 22, 2011). "KZN's very own screen wizard". The Witness. Archived from the original on April 24, 2014. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ^ a b Warner Bros. "Wizard of Oz Timeline". Warnerbros.com. Archived from the original on September 7, 2007. Retrieved September 10, 2007.

- ^ Democracy Now. November 25, 2004 Archived November 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Fricke, John; Scarfone, Jay; Stillman, William (1989). The Wizard of Oz: The Official 50th Anniversary Pictorial History. New York, NY: Warner Books, Inc. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-446-51446-0.

- ^ Fordin, Hugh (1976). World of Entertainment. Avon Books. ISBN 978-0-380-00754-7.

- ^ "Hollywood Reporter". October 20, 2005. [dead link]

- ^ Clarke, Gerald (2001). Get Happy: The Life of Judy Garland. Delta. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-385-33515-7.

- ^ Cemetery Guide, Hollywood Remains to Be Seen, Mark Masek Archived May 21, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Look Back at Making of 'Wizard of Oz'". ABC News. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^ Nissen, Axel (2007). Actresses of a Certain Character: Forty Familiar Hollywood Faces from the Thirties to the Fifties. McFarland & Company. pp. 196–202. ISBN 978-0-7864-2746-8. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ Lev, Peter (March 15, 2013). Twentieth Century-Fox: The Zanuck-Skouras Years, 1935–1965. University of Texas Press. pp. 67–68. ISBN 978-0-292-74447-9. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ Hearn, Michael Patrick. Keynote address. The International Wizard of Oz Club Centennial convention. Indiana University, August 2000.

- ^ a b Care, Ross (July 1980). "Two Animation Books: The Animated Raggedy Ann and Andy; John Canemaker; The Making of the Wizard of Oz . Aljean Harmetz" (PDF). Film Quarterly. 33 (4): 45–47. doi:10.1525/fq.1980.33.4.04a00350. ISSN 0015-1386. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved September 4, 2019.

- ^ Smalling, Allen (1989). The Making of the Wizard of Oz: Movie Magic and Studio Power in the Prime of MGM. Hyperion. ISBN 978-0-7868-8352-3.

- ^ Harrod, Horatia (December 25, 2015). "Stormier than Kansas: how The Wizard of Oz was made". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on May 9, 2020. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ Edwards, Owen. "Without This Camera, the Emerald City Would Have Been the Color of Mud". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved September 20, 2024.

- ^ Interview of Ray Bolger (1990). The Wonderful Wizard of Oz: 50 Years of Magic. Jack Haley Jr Productions.

- ^ Leopold, Ted (August 25, 2014). "'The Wizard of Oz' at 75: Did you know...?". CNN. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

Margaret Hamilton's copper-based makeup as the Wicked Witch was poisonous, so she lived on a liquid diet during the film, and the makeup was carefully cleaned off her each day.

- ^ Higgins, Scott (2000). "Demonstrating Three-Colour Technicolor: "Early Three-Colour Aesthetics and Design"". Film History. 12 (4): 358–383. doi:10.2979/FIL.2000.12.3.358 (inactive November 1, 2024). ISSN 0892-2160. JSTOR 3815345.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Aylesworth, Thomas (1984). History of Movie Musicals. New York City: Gallery Books. pp. 97. ISBN 978-0-8317-4467-0.

- ^ a b Harmetz, Aljean (2013). The Making of The Wizard of Oz. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-61374-835-0. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ^ a b "'I'll ruin you': Judy Garland on being groped and harassed by powerful Hollywood men". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- ^ Bertram, Colin (December 10, 2020). "Judy Garland Was Put on a Strict Diet and Encouraged to Take "Pep Pills" While Filming 'The Wizard of Oz'". Biography. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- ^ a b "Claims that Wizard of Oz munchkins molested Judy Garland deserve a response". ABC News. April 4, 2018. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- ^ ahcadmin (August 5, 2024). "Behind the Curtain: A Look at The Wizard of Oz's Difficult Production 85 Years Later". American Heritage Center (AHC) #AlwaysArchiving. Retrieved October 24, 2024.

- ^ Snyder, S. James (December 22, 2008). "Why Victor Fleming Was Hollywood's Hidden Genius". Time. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ^ Van Luling, Todd (August 25, 2015). "5 Things You Still Don't Know About 'The Wizard Of Oz'". Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ^ "The misery of Oz: How Hollywood starved its great star". Independent.ie. September 7, 2014. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^ Desta, Yohana (February 8, 2017). "Judy Garland Was Groped by Munchkins on Wizard of Oz Set, New Memoir Claims". Vanity Fair. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- ^ "Judy Garland 'sexually harassed' by munchkin co-stars on Wizard of Oz set". The Guardian. February 8, 2017. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- ^ White, Adam (February 8, 2017). "Judy Garland 'was molested by Munchkins' on the set of Wizard of Oz, according to late husband's memoir". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^ Adams, Thelma (October 17, 2017). "Casting-Couch Tactics Plagued Hollywood Long Before Harvey Weinstein". Variety. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- ^ Hejzlar, Zdenek; Worlund, John (2007), "Chapter 1: Scope of Phase I Environmental Site Assessments", Technical Aspects of Phase I/II Environmental Site Assessments: 2nd Edition, ASTM International, pp. 15–15–11, doi:10.1520/mnl11243m, ISBN 978-0803142732

- ^ "Cabin in the Sky (1943) Tornado Scene". YouTube. March 9, 2016. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- ^ Miller, Ron (2006). Special Effects: An Introduction to Movie Magic. Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 978-0-7613-2918-3.

- ^ Hogan, David J. (June 1, 2014). The Wizard of Oz FAQ: All That's Left to Know About Life, According to Oz. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-1-4803-9719-4.

- ^ "Smithsonian Will Stretch to Save Scarecrow's Costume, Too".

- ^ Scarfone, Jay; Stillman, William (2004). The Wizardry of Oz. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-1-61774-843-1. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ^ ""The Wizard of Oz" Cowardly Lion costume fetches $3 million at auction". CBS News. CBS/AP. November 25, 2014. Archived from the original on August 23, 2018. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- ^ "'The Wizard of Oz': Dark Secrets Behind the Making of the Hollywood Classic". August 24, 2018. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022.

- ^ Smythe, Philippa (September 2, 2019). "25 Wonderful and Weird Behind-The-Scenes Facts About The Wizard Of Oz". Archived from the original on November 3, 2023.

- ^ Rushdie, Salman (1992). The Wizard of Oz. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-85170-300-8. Archived from the original on August 19, 2020. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- ^ Eschner, Kat. "The Crazy Tricks Early Filmmakers Used To Fake Snow". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on August 21, 2018. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ^ McCulloch, Jock; Tweedale, Geoffrey (2008). Defending the Indefensible: The Global Asbestos Industry and its Fight for Survival. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-156008-8. Archived from the original on September 8, 2019. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- ^ "The Wizard of Oz 70th Anniversary News". Archived from the original on May 13, 2011.

- ^ "The Wizard of Oz [Original Motion Picture Soundtrack] – Original Soundtrack – Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards". AllMusic. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020.

- ^ The Wizard of Oz: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack – The Deluxe Edition, 2-CD set, original recording remastered, Rhino Records # 71964 (July 18, 1995)

- ^ Warner Bros. 2005 The Wizard of Oz Collector's Edition DVD edition, program notes and audio extras.

- ^ Orozco, Lance. "He Was a Hollywood Pioneer, but the Central Coast Man Is Now Largely Forgotten.” KCLU, KCLU, April 24, 2024, www.kclu.org/local-news/2024-04-24/he-was-a-hollywood-pioneer-but-the-central-coast-man-is-now-largely-forgotten. .

- ^ The Making of the Wizard of Oz – Movie Magic and Studio Power in the Prime of MGM – and the Miracle of Production #1060, 10th Edition, Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc./Random House, 1989.

- ^ ""The Wizard of Oz"... A Movie Timeline". Jim's "Wizard of Oz" Website Directory. geocities.com. Archived from the original on November 14, 2007. Retrieved September 10, 2007.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Archived from the original on January 25, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2019.

- ^ http://https://judygarlandnews.com/2018/08/10/on-this-day-in-judy-garlands-life-and-career-august-10/amp/.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Down The Yellow Brick Road: The Making of The Wizard Of Oz"McClelland, 1976 Publisher Pyramid Publications (Harcourt Brace Jonavich)

- ^ Williams, Scott (July 21, 2009). "Hello, yellow brick road". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Archived from the original on January 16, 2010. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

John Fricke, a historian who has written books about The Wizard of Oz, said that MGM executives arranged advance screenings in a handful of small communities to find out how audiences would respond to the musical adventure, which cost nearly $3 million to produce. Fricke said he believes the first showings were on the 11th, one day before Oconomowoc's preview, on Cape Cod in Dennis, Massachusetts, and in another southeastern Wisconsin community, Kenosha.

- ^ a b Cisar, Katjusa (August 18, 2009). "No Place Like Home: 'Wizard of Oz' premiered here 70 years ago". Madison.com. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

Oconomowoc's Strand Theatre was one of three small-town movie theaters across the country where "Oz" premiered in the days prior to its official Hollywood opening on Aug. 15, 1939 ... It's possible that one of the other two test sites – Kenosha and the Cape Cinema in Dennis, Massachusetts – screened the film a day earlier, but Oconomowoc is the only one to lay claim and embrace the world premiere as its own.

- ^ "Beloved movie's premiere was far from L.A. limelight". Wisconsin State Journal. August 12, 2009. p. a2.

- ^ "Grauman's Chinese Makeover: How the Hollywood Landmark Will Be Revamped". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- ^ Chan. (November 7, 1956). "Television reviews: Wizard of Oz". Variety. p. 33. Retrieved October 27, 2019 – via Archive.org.

- ^ Brooks, Tim; Marsh, Earle (2003). "Ford Star Jubilee". The Complete Directory to Prime Time Cable and Network Shows 1946 – present. Ballantine Books. p. 425. ISBN 978-0-345-45542-0.

Last telecast: November 3, 1956 ... The last telecast of Ford Star Jubilee, however, was really something special. It was the first airing of what later became a television tradition – Garland's classic 1939 film The Wizard of Oz, with Judy's 10-year-old daughter Liza Minnelli and Lahr (the Cowardly Lion from the film) on hand to introduce it.

- ^ a b "Hit Movies on U.S. TV Since 1961". Variety. January 24, 1990. p. 160.

- ^ "Feature Films on British Television in the 1970s". British Universities Film & Video Council.

- ^ "MGM/CBS Home Video ad". Billboard. November 22, 1980. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- ^ Julien Wilk (February 28, 2010). "LaserDisc Database – Search: Wizard of Oz". Lddb.com. Archived from the original on August 16, 2012. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- ^ "WOO CED Exclusive". Archived from the original on November 25, 2014. Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- ^ "The Wizard of Oz (1939) 3D". Prime Focus World. Archived from the original on April 21, 2016. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- ^ "Off To See The Wizards: HDD Gets An In Depth Look at the Restoration of 'The Wizard of Oz'". Highdefdigest.com. September 11, 2009. Archived from the original on February 12, 2010. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- ^ The Wizard of Oz Blu-ray Release Date December 1, 2009, archived from the original on April 7, 2020, retrieved March 5, 2020

- ^ The Wizard of Oz DVD Release Date March 16, 2010, archived from the original on April 7, 2020, retrieved March 5, 2020

- ^ a b "'Wizard of Oz' coming back to theaters for IMAX 3D run". Archived from the original on June 16, 2013. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ "'Wizard of Oz' Goes 3D for W.B. 90th Celebration". ETonline.com. October 3, 2012. Archived from the original on December 10, 2012. Retrieved November 2, 2012.

- ^ "WOO Best Buy SteelBook Exclusive". Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- ^ "WOO Target Exclusive". Archived from the original on November 23, 2018. Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- ^ The Wizard of Oz 4K Blu-ray Archived August 26, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. Blu-ray.com. August 23, 2019.

- ^ "Wizard of OZ: 85th Anniversary Theater Edition 4K Blu-ray".

- ^ Cruz, Gilbert (August 30, 2010). "The Wizard of Oz". Time. Archived from the original on December 18, 2011. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ "The Wizard of Oz (1939, U.S.)". Kiddiematinee.com. November 3, 1956. Archived from the original on January 12, 2010. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- ^ "The Wizard of Oz (2002 re-issue) (2002)". boxofficemojo.com. Archived from the original on November 24, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- ^ "The Wizard of Oz 70th Anniversary Encore Event". Creative Loading. November 17, 2009. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- ^ Graser, Marc (August 28, 2013). "Warner Bros. Plans $25 Million Campaign Around 'The Wizard of Oz'". Variety. Archived from the original on September 2, 2013. Retrieved September 11, 2013.